A Quarantine Island, Abandoned Railroad, and More NYC Ruins That May Soon Be Reclaimed

Although it sometimes seems today’s New York City is made up of nothing but brand new, ultra-luxury, high-end condominiums, it is still scattered with an incredible number of derelict buildings, abandoned historical sites, and disused infrastructure spaces. The most high-profile recent ruin repurposing is the High Line — 1.45 miles of disused railway tracks made over into a linear park, the final piece of which opened just last month. The project was massively successful, especially in terms of rising real estate prices nearby and a huge influx of tourism in the neighborhood. It also inspired imitators: a West Harlem resident recently came forward with a proposal for a similar project, which would involve selling the air rights above a rail line to pay for the park, and then using them to create an affordable housing district.

Here are five more NYC ruins, from the Bronx to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, that may soon be given new lives:

QueensWay

Queensway (photo by Jim.henderson, via Wikimedia)

Queensway (photo by Jim.henderson, via Wikimedia)

Also inspired by the High Line is the plan to convert the QueensWay. The 3.5 miles of rail tracks between Rego Park and Ozone Park — known as the Rockaway Beach Branch that once served the LIRR’s Rockaway Beach line — seem to be moving ahead into an elevated park. “The QueensWay is like the High Line on steroids: It’s more than twice as long and seven times the acreage,” Adrian Benepe of the Trust for Public Land told CBS New York.

The proposed project will cost in the neighborhood of $120 million, and is not without its detractors — opponents would rather see the rail line itself restored, which would increase transportation options to an underserved section of Queens. But the current proposal includes walkways, biking trails, a wetland habitat and bioswale, and outdoor classrooms. It’s possible construction could begin early next year.

The Lowline

Exhibition with a prototype for the Lowline (photograph by Bit Boy/Flickry)

Although projections put the opening of the Lowline at around 2018, the idea has already been tantalizing New Yorkers for several years. The proposal to reappropriate the 1.5 acre Williamsburg trolley terminal to create the world’s first underground park was made public in 2011, and has received tremendous media coverage and both official and popular support, including a record-breaking Kickstarter that raised more than $155k from 3,300 donors.

The trolley terminal, which was built in 1903 and abandoned since 1948, runs for three blocks under Delancey Street on the Lower East Side. The park will be lit and powered by a combination of LEDs and a new kind of fiber-optic technology called a “remote skylight,” which, in addition to pulling enough sun from street level to light the park, is also strong enough for photosynthesis, enabling plants to grown beneath the ground.

As the Lowline website states, “We envision not merely a new public space, but an innovative display of how technology can transform our cities in the 21st century.” An engineering firm has priced the project at a mere $55 million.

Admiral’s Row

Admiral’s Row (photograph by Bitch Cakes/Flickr)

Admiral’s Row (photograph by Bitch Cakes/Flickr)

Another site treasured by urban explorers and lovers of derelict buildings is the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s Admiral’s Row, 10 absolutely ruined 19th-century buildings that once housed the Navy Yard’s senior officers. The Yard was closed in 1966, but ownership of the buildings on Admiral’s Row was not transferred to the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation (BNYDC) until 2012, by which time even getting near the buildings to assess their damage was determined to be perilous.

All the buildings have been deemed too far gone to salvage save two: Quarters B and the Timber Shed, which will most likely be spared for renovation. The rest will be leveled and redeveloped as a large grocery store and retail complex to serve the nearby housing projects, an area considered to be a food desert. The BNYDC estimates the redevelopment cost at about $100 million and has put out a call for proposals three times. In 2012, PA Developers were selected, but they had to be replaced due to a bribery scandal involving one of the firm’s principles. In 2013, the Blumenfeld Development Group was chosen, but the firm was removed after it “failed to meet its end of the contract.” In July of 2014, the BNYDC put out yet another request for proposals; it remains to be seen who will win the bid.

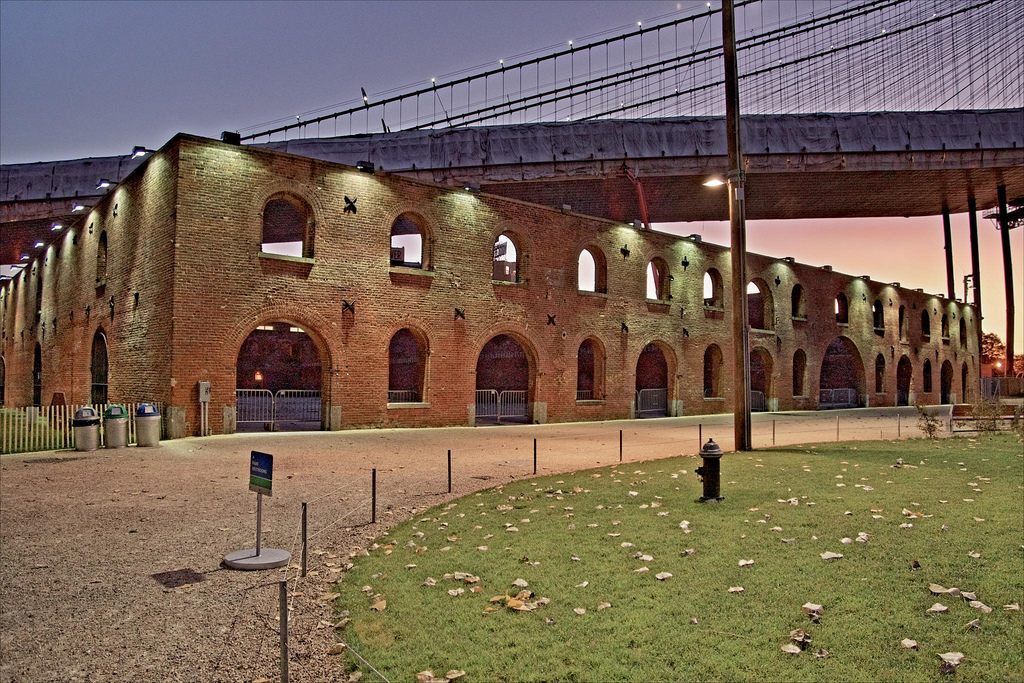

Tobacco Warehouse

Tobacco Warehouse (photograph by Ed Costello/Flickr)

Tobacco Warehouse (photograph by Ed Costello/Flickr)

The Tobacco Warehouse was built in the 1870s by the Lorillard family as a custom inspections facility for goods coming in from the waterfront. The building was saved from demolition in the 1990s and, though roofless and windowless, has been used sporadically since then as an outdoor venue for performances and festivals, as well as a second location for the Williamsburg-based foodie bonanza Smorgasburg.

In 2011, the Brooklyn Bridge Development Corp. accepted a proposal from award-winning performing arts institution St. Ann’s Warehouse to redevelop the building (well, accepted then rejected then accepted again). The new structure, which will cost around $30 million, will have two performance areas, a multi-use community space, and an open courtyard. Construction is expected to be finished in the fall of 2015; in the meantime, DumboNYC has some renderings of how it will eventually look.

North Brother Island

North Brother Island (photograph by Jessica Sheridan/Flickr)

North Brother Island (photograph by Jessica Sheridan/Flickr)

This remains merely speculative, but even the potential rehabilitation of one of New York City’s most fascinating islands is a big deal. North Brother, 20 acres off the Bronx coast near Riker’s, was a quarantine hospital starting in 1885, famously housing Typhoid Mary off and on over the course of her life. It was also the site of the conflagration and shipwreck of the General Slocum, and was used as a drug treatment facility until the early 1960s. The island has been abandoned ever since, and is now teeming with wildlife, from invasive kudzu to previously endangered wild herons. It’s a favorite haunt for urban explorers and lovers of ruin porn, but is strictly off-limits to the public.

However, Mark Levine, the City Council’s parks committee chair, would like to see that changed. “We want to start building the momentum and constituency for opening this up in some way,” Levine told the New York Times. At this point there’s no actual plan to determine how to stabilize the island’s more than 25 incredibly derelict buildings — even commissioning a study to assess what would need to be done would cost millions.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook