A Condensed History of Quarantine’s Success and Failure

Ebola facility in Sierra Leone, August 2, 2014 (©EC/ECHO/Cyprien Fabre)

Ebola facility in Sierra Leone, August 2, 2014 (©EC/ECHO/Cyprien Fabre)

Death, disease, and fear ravage much the world right now, as thousands die of Ebola in West Africa, and hundreds of thousands across the globe read about it. In such a climate, it only makes sense to quarantine the affected areas to stop the swell of infection, or does it?

Sitting at home, our idea of a quarantine probably brings to mind one of two images. The first is a humane and sanitary containment system, where victims are tended to by healthcare workers versed in precautionary measures to prevent spread, and perhaps a second containment system for those who may have been in contact with the disease, so that those who are not infected remain so, and those who are can be swiftly moved to the correct facility. The other image is that of the dystopian novels, where thousands of people — sick and well — are left to fend for themselves in abandoned stadiums or hospitals, as the rest of the word metaphorically throws red tape around the area and walks away.

Sadly, the reality of quarantine is closer to the second image than the first, and it may even be more dire than that.

In August this year, military forces surprised citizens in a neighborhood of Monrovia, Liberia, with a “cordon sanitaire.” Makeshift roadblocks of old scrap wood were forcibly placed around the area of West Point, a densely populated slum where education is minimal and health care is virtually nonexistent. The residents of the neighborhood were not informed of this blockade, were not made aware of its purpose or the reasoning behind it. They were expected to comply with brute force, as the government there scrambled, feeling they had no time for communication.

In these conditions, can we really blame victims of the disease and their possibly infected loved ones for breaking out of (or into) the neighborhood?

As much common sense as it may make to first-world countries trying to stop a deadly disease, quarantines have always walked the thin line between healthcare and human rights violations. It has been well-documented that the difference between these two outcomes is efficient and strong communication. Something we have not achieved in West Africa.

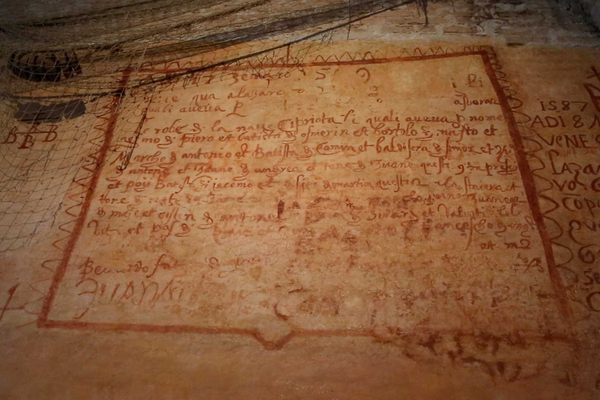

Cordon sanitaire is a specific type of quarantine that uses physical barriers to mark an area of disease or military aggression. Its first known use as a phrase stems from France in 1821, when the French government sent 30,000 troops to the Pyrenees to stop a deadly fever from traveling from Spain into their country. Quarantines of this nature have been in use since the 1500s, often used in medieval times to thwart the bubonic plague. 2014 is the first year one has been government sanctioned since 1918, when the border between Russia and Poland was closed to prevent spread of typhus.

In almost all cases of use, cordon sanitaire is a last resort, implemented when the cause and spread of a disease is unknown. As some residents of parts of West Africa are condemned to a dystopian reality, it is worth looking at the history of quarantines, and the diseases they were meant to prevent.

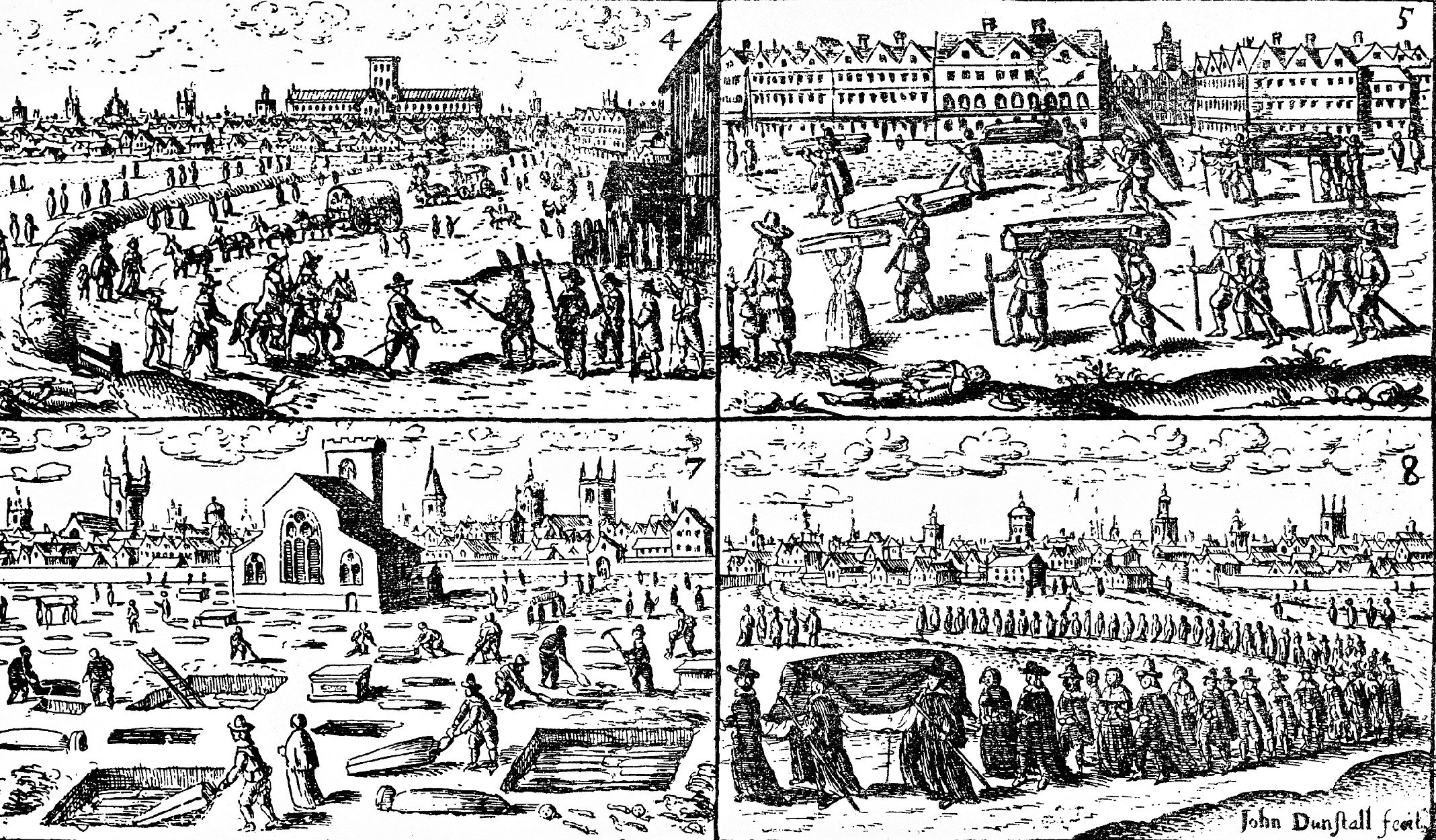

Bubonic Plague: 1665

Scenes of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (via Wellcome Images)

Scenes of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (via Wellcome Images)

In 1665, England experienced its last epidemic of the deadly bubonic plague that had been prevalent since the 1400s. Top estimates say it killed 100,000 of London’s 460,000 citizens. While we now know the plague is spread by fleas from rats, in those days little was known about the origin of the disease. As is common, the infection stemmed from a destitute area.

In the small town of St. Giles, west of London, rats carrying the disease made their way through alleyways strewn with garbage into Whitechapel, then London itself. Quarantines were immediately set in place, the houses of the infected locked, and churches prohibited from keeping bodies on their property. Those who died of the bubonic plague were carried away at night and thrown into plague burial pits. By September of 1665, however, quarantine measures were abandoned. Those who could afford it fled the country, leaving the impoverished and already-sickened to their own devices. Parliament ceased activity. What actually stopped the disease in 1666 was not quarantine measures (as they were carried out haphazardly and not adhered to properly), but a great fire that burned nearly all of the city, taking the plague with it. The city rebuilt itself with wider streets and implemented stricter sanitation codes to prevent another epidemic from taking place.

Cholera: 1830 - 1920

Quarantined children of cholera victim (early 20th century) (via Library of Congress)

Quarantined children of cholera victim (early 20th century) (via Library of Congress)

The 19th century could virtually be defined by the various outbreaks of cholera all over the world, as transportation improved and cross-country travel became possible. With origins in India, cholera is most known for its outbreaks in London and New York in the early 1830s. Again, the disease hit hardest in the poorest neighborhoods, where health standards and sanitation were not enforced. A highly respected civic leader at the time, John Pintard, wrote that “the epidemic is almost exclusively confined to the lower classes of intemperate dissolute & filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations.” He went on to encourage allowing the sick to die off, calling them the scum of the earth. When quarantines are not equipped with communication and easily available aid and food, this is essentially what happens anyway.

We now know that cholera is spread via food and water that has come in contact with fecal matter, but in the 1830s the idea was that people were spreading it to each other. When it arrived in England in 1831, the Privy Council put all ships arriving from Russia under quarantine. In New York in the summer of 1832, the opposite occurred. There are reports that 100,000 people out of a population of 250,000 fled the city. Another 3,515 perished.

During the subsequent American fears of an outbreak in the early 1890s, the media were hard at work quelling hysteria, stating that controlling the disease was simply a matter of sanitation and disinfection. Even still, all ships coming into New York’s harbor were quarantined for a time, as that same media maintained that adequate sanitation and disinfection could not take place on a boat.

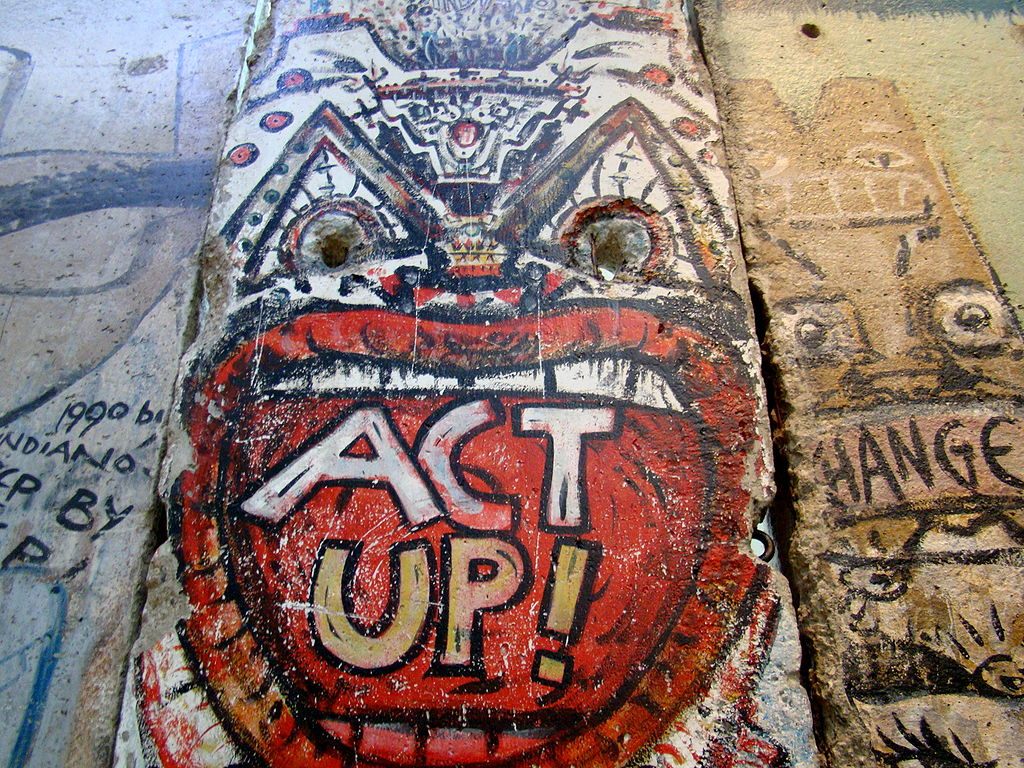

AIDS: 1985-1986

Act Up!, AIDS activism art on the Berlin Wall (photograph by Queerbubbles/Wikimedia)

While a large-scale quarantine was never approved for AIDS victims and those with HIV, several polls and legislation were crafted around the issue when the United States struggled to contain yet another disease without knowing how it spread. Only this one had a bad guy. Gay people. In one case, police in Atlanta apprehended a man who ended up having a bloody nose in the back of the squad car. The car itself was placed under quarantine for 21 days, and would have been there indefinitely if the state’s assistant epidemiologist hadn’t gone to the pound lot, and washed the car out with disinfectant. The police claimed they simply didn’t know what to do with it.

While many thought an AIDS quarantine was a good idea, 51 percent of Americans polled at the time favored programs to protect homosexuals from being discriminated against in the workplace, but 55 percent said they would take their child out of school if one of the other children was known to have HIV or AIDS. Meanwhile, 51 percent favored a full-on quarantine for AIDS victims, going so far as to suggest visible tattoos to differentiate them from the general population.

SARS: 2003

photograph by Teresa Folaron/Flickr

photograph by Teresa Folaron/Flickr

During the SARS epidemic from March to July of 2003, 30,000 residents in Beijing were quarantined. The virus took 778 lives, and more than 8,000 people contracted the disease. Spread by coughing and sneezing, this quarantine made sense as the severe acute respiratory syndrome spread to cities in the United States, Europe, and Canada; however the quarantine measures taken in Canada were labeled ineffective and inefficient.

Scholars were also shocked at the first quarantine measures being used there in well over a century. They maintain that Toronto quarantined 25 times more people than necessary to prevent the spread of the disease. Only 57 percent of those “forced” into quarantine were compliant, and apparently with good reason. Toronto health officials quarantined 100 people for every SARS case, whereas China quarantined only 12 for every case.

H5N1 (Bird Flu): 2005

Poster in Vietnam warning against H5N1 (photograph by Joe Gatling/Flickr)

Poster in Vietnam warning against H5N1 (photograph by Joe Gatling/Flickr)

On July 18, 2005, Dr. Henry Niman wrote of the forced quarantine measures taken in China to prevent the spread of a deadly flu strain, H5N1. By the time the government responded to the province impacted, several people were afflicted with intense pneumonia. The quarantine was not well explained, and forcing people to cordon themselves off from their lives caused them to “lose control of themselves and revolt against the authorities,” resulting in many extra casualties. The people were told nothing. Many farmers thought it was “nothing, just a fight over a bunch of birds.”

***

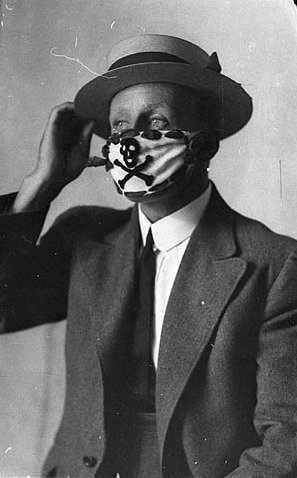

A compulsory mask for a post-WWI flu epidemic in Australia (via State Library of New South Wales)

A compulsory mask for a post-WWI flu epidemic in Australia (via State Library of New South Wales)

Of course, quarantine is used on an individual basis quite often, mostly for diseases like tuberculosis which spread easily through the air. The key, though, is that these are isolated, individual cases where a patient gives consent to give up certain rights while harboring the disease for the sake of public safety. There have been documented cases of forced isolation for tuberculosis patients, and these bring up ethical dilemmas that the world has yet to face. Thankfully, the instances are few and far between. But that doesn’t mean we should ignore the ethical implications of quarantine. We need to look at public safety, at human rights, at education, sanitation, aid, food and treatment options, and write down a policy that is comprehensive so that the next time a disease breaks out worldwide, our leaders have a plan to follow.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook