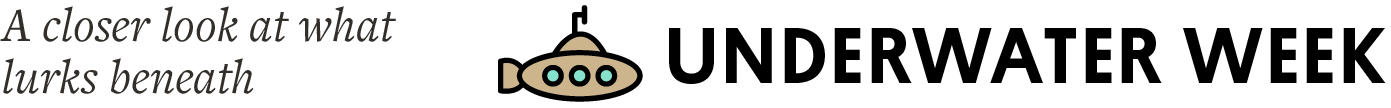

A Graphic Guide to All the Weird Things in New York City’s Waterways

The digital journal Underwater New York tells the stories of objects submerged and washed ashore.

(Graphic by Michelle Enemark)

Dead Horse Bay is a sloshing soup of forgotten ephemera. Old shoe soles, broken bottles, fractured horse bones from 19th-century rendering factories and landfills are some of the odd objects that momentarily surface before being swallowed back into the tide. To most people, this beach on the outskirts of southern Brooklyn, New York looks like a swamp of garbage, but for writer, curator, and historian Nicki Pombier Berger, Dead Horse Bay is a playground for the imagination.

“It’s not contemporary trash like tampon applicators and Coke bottles—it’s visibly distant-in-time trash,” Berger says, who wrote a short story titled “Cold” after discovering a green teacup washed up at Dead Horse Bay. “If you just look closely when you’re there, you’ll wonder what was here before? Where is all this coming from?”

New York City waterways, like Dead Horse Bay, and their unexpected treasures serve as inspiration for artists, filmmakers, musicians, photographers, and storytellers who contribute to the digital journal, Underwater New York. Berger and two fellow editors, Helen Georgas and Nicole Haroutunian, curate a list of waterfront objects (lost and found, submerged or surfaced). The project prompts people to use one or multiple objects as a stepping off point to create a new piece of art.

Underwater New York editors Nicole Haroutunian, Helen Georgas, and founding editor Nicki Pombier Berger at Dead Horse Bay. [Photo: © Adrian Kinloch]

Underwater New York editors Nicole Haroutunian, Helen Georgas, and founding editor Nicki Pombier Berger at Dead Horse Bay. [Photo: © Adrian Kinloch]At last count, there are 150 objects on the list ranging from a bag of lottery tickets, to a robot hand, and toppled decaying ships. The map above highlights 10 fascinating objects from Underwater New York’s list—some that you can go out and see in-person.

Underwater New York started off as a kind of writer’s workshop. Berger came across an article in New York magazine published in May 2009 that revealed 28 of bizarre and fascinating things beneath the surface of New York Harbor, including a piano and a dead giraffe. She used the items in the article as a writing exercise with friends, but when more people became interested the idea quickly grew into a project. After teaming with developers and designers, Underwater New York launched at the end of the summer.

Underwater New York editor Nicole Haroutunian illustrated this rendering of a grand piano for a series of sketches called “Beside,” which features her favorite objects on the list. [Photo: Nicole Haroutunian/Underwater New York]

“We had this concept and we continued adding objects to the list as we found them through articles that came our way or through anecdotes that people shared with us,” Berger says, explaining that it’s quite easy to get an interesting underwater object on the list. “Someone tells me they saw it, and we usually add it.”

Underwater New York has grown tremendously since Berger founded the journal in 2009. Now, the website is home to an extensive body of original fiction, music, and artwork from over 100 contributors, and the editors have collaborated on larger projects with museums and magazines. Underwater New York has encouraged artists to explore the city in a new way, even leading excursions out to secluded waterfronts.

What other mysteries lie beneath New York’s waters? [Photo: NASA/Public Domain]

What other mysteries lie beneath New York’s waters? [Photo: NASA/Public Domain]Even though she trembles at the thought of scuba diving, Berger is fascinated by what remains unseen underwater.

The waterfront defines a city, she says. Working on Underwater New York and venturing out to different beaches and bays has changed her spatial sense of New York City.

Imagining what’s underwater “helps expand the edges of the city beyond land, beyond the hard vertical and horizontal lines that we move through in the city,” she says. “It’s just a reminder of how the city is actually fluid, and change is constant.”

Here’s a closer look at some of the historical and mysterious articles adrift in New York’s waters.

Thousands of Bottles (Dead Horse Bay)

A photo of a washed-up bottle in the photoseries “Dead Horse Bay,” by artist Adel Souto. [Photo: Adel Souto/Underwater New York]

A photo of a washed-up bottle in the photoseries “Dead Horse Bay,” by artist Adel Souto. [Photo: Adel Souto/Underwater New York]“Today my own little girl broke a teacup – the green one painted with a family on a hillside, all that space to breathe – and I sent it like a missive to the trash. Tomorrow a team of horses will cart it off to the island with the rest, and soon enough the horses themselves will be worn by life into bodies, borne to Barren Island, boiled into bone.” – from the short story “Cold,” by Nicki Pombier Berger

Nicknamed “Bottle Beach,” the shores of Dead Horse Bay are filled with thousands of seaweed and brine covered bottles that date back hundreds of years. Every time you visit the cluttered beach of Dead Horse Bay, you’re bound to stumble across something new. The objects clinking and lulling in the waves are remnants of an island that is no longer an island.

Dead Horse Bay and the Floyd Bennett airfield were once a smelly marshland called Barren Island. From the 1850s to the early 20th century it was populated by Polish, Dutch, and Italian immigrants and dominated by the stench wafting from rendering facilities. Each day, horse carcasses from all five boroughs were brought to Barren Island’s factories to produce glue and fertilizer—a process emitting odors so strong that some organizations in mainland Brooklyn tried to shut the operation down.

After World War I, the industry slowly died and Robert Moses, the former city parks commissioner, envisioned the area as a gateway national recreation park. He decided to build the Bennett airfield and in 1926 the surrounding waters of Barren Island were filled with sand, coal, and trash, connecting it to the rest of Brooklyn. In the 1950s, the area was used as a landfill, one of which burst, hurtling trash from the early 20th century into the bay.

The waterway is sealed off from the rest of Brooklyn by tall swaying sea oaks. In order to reach it, you must trek down a winding trail at the end of Flatbush Avenue by foot until you emerge in front of a vista awash with all kinds of historical objects waiting to be discovered. You can visit Dead Horse Bay this coming August with Underwater New York.

Tugboat Graveyard (Arthur Kill)

An abandoned tugboat at Arthur Kill. [Photo: Nate Dorr/Underwater New York]

An abandoned tugboat at Arthur Kill. [Photo: Nate Dorr/Underwater New York]“Arthur Kill, that slim waterway that prevents Staten Island from being a part of New Jersey, has a surplus of discarded watercraft. Scuttled, sunken, or just eternally moored.” – from the photoshoot “Arthur Kill,” by Nate Dorr.

You know you’re getting closer to the tugboat graveyard the more your shoes sink into the muddy marshland of Arthur Kill tidal strait. Recognized as the official dumping ground for old, wrecked ships, the fleet of decrepit ghost crafts rusting in the polluted water between Staten Island and New Jersey have inspired photographers and documentarists.

In the 1930s, John J. Witte started the Witte Marine Equipment Company, a business that scavenged ships for usable parts. However, it couldn’t keep up with the influx of decommissioned ships, and the crafts began rotting so quickly it was difficult to salvage anything. By 1990, Arthur Kill was a floating wasteland of wood and metal, with about 200 shells of ships resting in their watery graves.

Today, there are fewer than 25 ships that can be seen at the tugboat graveyard. Among them are the historical U.S.S PC-1264 submarine chaser, which was the first World War II U.S. Navy ship to have a predominantly African American crew, and the NYC Fire Department fireboat Abram S. Hewitt.

1,600 Bars of Silver (Arthur Kill)

Painter and book maker Sarah Mostow wrote and illustrated the book If You Look, which features objects below water. This is an original painting inspired by the 1,600 bars of silver. [Photo: Sarah Mostow/Underwater New York]

Painter and book maker Sarah Mostow wrote and illustrated the book If You Look, which features objects below water. This is an original painting inspired by the 1,600 bars of silver. [Photo: Sarah Mostow/Underwater New York] In September 1903, the ship Harold carried very precious cargo. Stacked on its foredeck were 7,678 ingots of silver mined from the interior mountains of Mexico. Each bar was two feet in length, weighed 100 pounds, and consisted of approximately 75 percent silver and 25 percent lead.

The Harold was making its way up the shallow waters of Arthur Kill in a string of towed ships. Early in the morning at 2 a.m. when the captain was asleep, the vessel suddenly pitched sharply starboard, causing the stack of silver bars to topple across the deck and plunge into the dark waters, W.C. Jameson wrote in the book Buried Treasures of the Mid-Atlantic States.

Divers immediately began to search the channel for the missing silver. For a week, they came up empty handed, and the crew began to suspect that the ship had been hijacked. Eventually, a few bars were found around the coast of Sewaren, New Jersey. Over the next ten days, the divers recovered over 6,000 silver bars, leaving behind about 1,600 scattered in Arthur Kill. Small independent attempts have been made over the years to find the lost silver, but none have been successful. Perhaps new seafloor surveying equipment may help locate them.

“At an estimated value of several millions of dollars, the treasure may well be worth the wait,” Jameson writes.

Homemade Submarine (Coney Island Creek)

Quester I stuck in the mud of Coney Island Creek. [Photo: © Candy Delaney]

Quester I stuck in the mud of Coney Island Creek. [Photo: © Candy Delaney]There are many abandoned ships sunken in Coney Island Creek, but perhaps one of the most famous crafts is the ill-fated submarine, Quester I. The 45-foot, chromium yellow painted submarine was built in 1967 by local shipyard worker Jerry Bianco. He built Quester I to try to raise and excavate the sunken Andrea Doria, an ocean liner submerged in the Atlantic Ocean after colliding with another ship in 1956, the New York Times reported.

It is said that the wreckage of Andrea Doria contains valuable artifacts. After three years, Bianco was ready to launch his scrap metal submarine. While lowering it down with a crane, the vessel’s structure didn’t allow it to balance properly causing it to tip sideways and become stuck in the mud. Bianco tried to recover the Quester I, but couldn’t raise the funds. Today, Bianco’s self-made submarine—poking above the Coney Island Creek’s waves—has a sheen of orange rust in addition to the bright yellow paint of the cap.

Infographic by Michelle Enemark.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook