A Dry Town Goes Wet After More Than a Century

Pitman, New Jersey, got a taste of booze this month.

Kelly Green Brewing Co. on Broadway in Pitman, NJ. (Photo: Jackson Kuhl)

On its second night open, Kelly Green Brewing Co. unlocked its front door promptly at 5 p.m. By 5:05 the line from the bar stretched to the door; by 5:30, it was over the threshold and onto the sidewalk. Behind the counter, a bartender told patrons they would have to wait a few minutes for the beer they wanted–the tap had already sputtered and a keg swap was in process. It was a Thursday.

“This town is thirsty,” said Justin Fleming, a Kelly Green co-owner. And no wonder: Kelly Green is the first place to serve beer in the borough of Pitman, New Jersey, since 1871. The historically dry town of 9,000 citizens has gone wet.

Drinking alcohol was never really illegal in Pitman–you just had to cross the town line to get it. While the state regulates alcohol in New Jersey, municipalities control the issuance of liquor licenses. Pitman has never issued licenses, resulting in an orbit of bars and package-good stores just outside the border. But in 2012, New Jersey amended its laws to allow microbreweries to sell their beer for consumption on the premises. Since these brewery licenses come from the state government, the microbreweries don’t require a local license to operate. In other words, they don’t actually need the town’s permission to make and serve beer.

The line at 5:30pm on a Thursday evening. (Photo: Jackson Kuhl)

Located across the Delaware River about 15 miles south of Philadelphia, Pitman has a long history of temperance. The town began as a Methodist meeting camp–and Methodists are teetotalers. Since at least the 1790s, preachers of various stripes–mostly Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians–would organize countryside worship services, in the open air or inside a tent or simple pavilion. Farmers and frontiersmen with time on their hands would travel to the site, pitch a tent, and spend a week or two relaxing and hearkening to sermons.

By the Victorian period, “vacation camp meetings” to escape the urban swelter were popular for Methodists. Some 600 tents were pitched for the first camp meeting in August of 1871. For 10 days straight, preachers paraded across the tabernacle stage at 10 a.m., 2:30 p.m., and 6 p.m. By the following year, an estimated 10,000 people attended the camp. “The woods is literally full,” said an early Pitman camp goer. “One boarding house fed 1,000 for dinner. Good Preaching.”

Soon, concessions were granted to restaurants, a barber, a butcher, and other services to set up just outside the Grove area. Meanwhile the campers, dissatisfied with sleeping on straw in canvas tents, began building cottages on the lots, icing their eaves with gingerbread moldings. Gas lights were installed along the boulevards and the camps ran longer, with the menfolk commuting 26 minutes by train to their jobs in Philadelphia. Families began living in their cottages year-round, and by 1905 there were enough of them to establish the borough of Pitman.

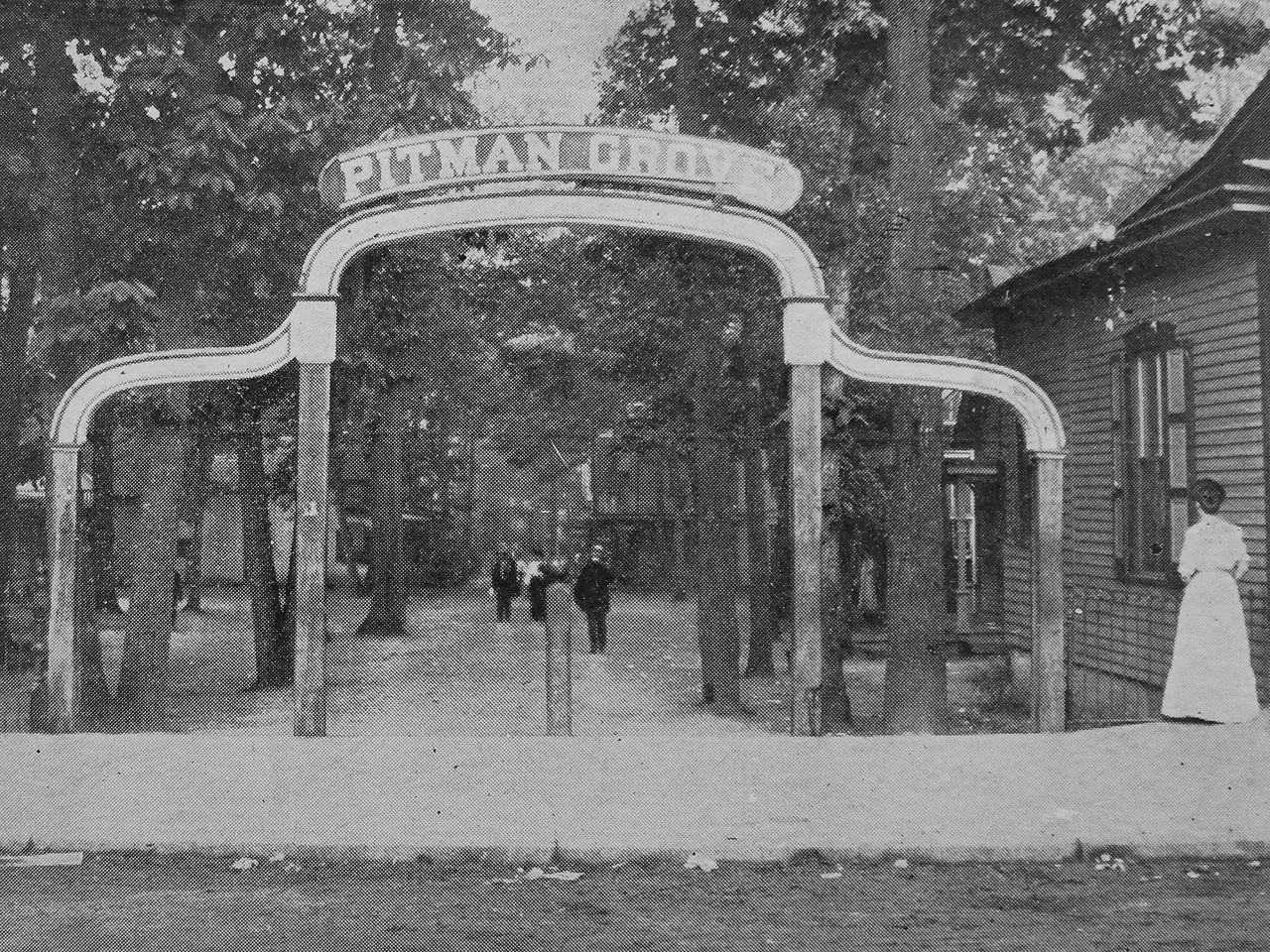

The original entrance to the Pitman Grove. (Photo: Courtesy of the Pitman Museum)

The New Jersey Conference Camp Meeting Association, the Methodist group which organized the camp at Pitman, forbade a number of behaviors in their lot leases. No liveries or stables were allowed (horses were kept outside of the Grove for sanitation); no businesses could operate on the Sabbath; and most of all, absolutely no manufacture or sale of “spirituous malts, intoxicating liquors of any grade or preparation, or substance in nature thereof.”

This in turn became a selling point for the borough: a 1906 pamphlet encouraging immigration touted Pitman’s anti-saloon policies, a tradition that carried down to the present day. (Not everybody seems to have read the pamphlet: that same year, a measure before the council called for the establishment of a town prison to house the many drunks wandering Pitman’s temperate lanes.)

But after more than a century of being a dry town, last December Pitman’s council voted 4-2 in favor of the town solicitor drafting language for an ordinance to finally issue liquor licenses. This was somewhat of a sea change: In 2007, 61 percent of voters defeated a public referendum to issue liquor licenses; but in 2013, perhaps due to an influx of young families, an ordinance passed overwhelmingly to allow BYOB drinking at restaurants with outdoor seating.

According to Pitman Mayor Russell Johnson, the councilman who pushed for the vote did so on economic grounds. “We already have wine being sold in town and will have beer being sold, but the town receives no revenue from it,” Johnson said.

A vintage postcard of the Pitman Grove cottages. (Photo: Courtesy of the Pitman Museum)

As a planned community, Pitman has seen better days commercially. Its main drag, Broadway, is straight and wide, anchored by the vaudeville-era marquee of the Broadway Theatre, still in use today. But of the 52 storefronts tallied between Broadway’s main cross-streets, almost a fifth are vacant. The roof of an imposing Greek revival bank is collapsing, while across the street, the former Bob’s Hobbies–containing an estimated 10,000 feet of retail space–sits empty.

“We’re hoping the breweries will help attract other businesses,” says Mayor Johnson. That’s breweries plural; a second microbrewery, Human Village, is slated to open two doors down from Kelly Green this summer.

Fleming and his wife Jeanette, who along with friend David Domanski co-own Kelly Green, are born-and-bred Pitmanites who believe a microbrewery is the vaccine for the town’s ills. “We saw that it was a dry town, kind of struggling,” Justin said, explaining why they chose the location on south Broadway.

The entrance to the Pitman Grove today. (Photo: Jackson Kuhl)

About six years ago, the two men decided they needed a hobby, and an ad for a brew kit popped up on Domanski’s computer screen. Fast forward to last year, when Fleming quit his job as a security guard working the third shift at the Salem Nuclear Power Plant to open Kelly Green under New Jersey’s revised limited brewery license.

The license is very specific to distinguish microbreweries from bars. Kelly Green can only sell beer “in connection with a tour of the brewery,” so a flatscreen in the corner there loops a video of Kelly Green’s crew making beer while a window in the taproom allows patrons a peek into the back-of-house workings. They’re not allowed to sell food or operate a restaurant, so the bowls of pretzels on the tables are free.

Kelly Green certainly fills a vacuum for a neighborhood tavern. On a recent Thursday evening, two old-timers leaned against the bar like they had been there for 20 years. A group of strangers ticked other South Jersey breweries off their craft-beer tourism lists. Young parents wearing Baby Bjorns parked their strollers on the sidewalk and joined the line. A return visit on Friday revealed lines chalked through several beers on the menu.

“The [attention] is high for us,” said Fleming, noting they’re not only the first microbrewery in Pitman but in the entire county. “There’s aspects relying on us to bring a spotlight to this town.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook