Animals Are the Earth’s Sensors. Here’s How Scientists Track All Their Data

A female lion crosses the Kenyan savanna wearing a tracking collar. (Photo: Roland Kays)

Until recently, if researchers wanted to track quarry in the wild, they had to catch them, affix them with electronic tags that transmitted radio signals and then physically follow them around. They received few points, the data was not always accurate, and the technology was expensive. It was also bulky, and couldn’t be applied to smaller animals.

But GPS has changed all that. The tools are smaller, cheaper, and energy efficient. Their signals can be picked up from remote locales, such as rainforests, beaming real time data to cell and satellite networks. Some are solar-powered, others offer monitoring tools that track body movement, heart rate, and temperature. “We can now document birds’ flight behavior as if they were airplanes carrying advanced aerospace technology,” Roland Kays, the head of the Biodiversity Research Lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, and his collaborators wrote in a 2015 paper.

Now, scientists are grappling with millions of data points instead of a few dozen, an achievement that Kays has compared to the electron microscope, sequencing the human genome and weather radar. So what to do with all that data?

Biologist Roland Kays inspects a GPS tracking collar on a tranquilized kinkajou in Panama. (Photo: Courtesy Roland Kays)

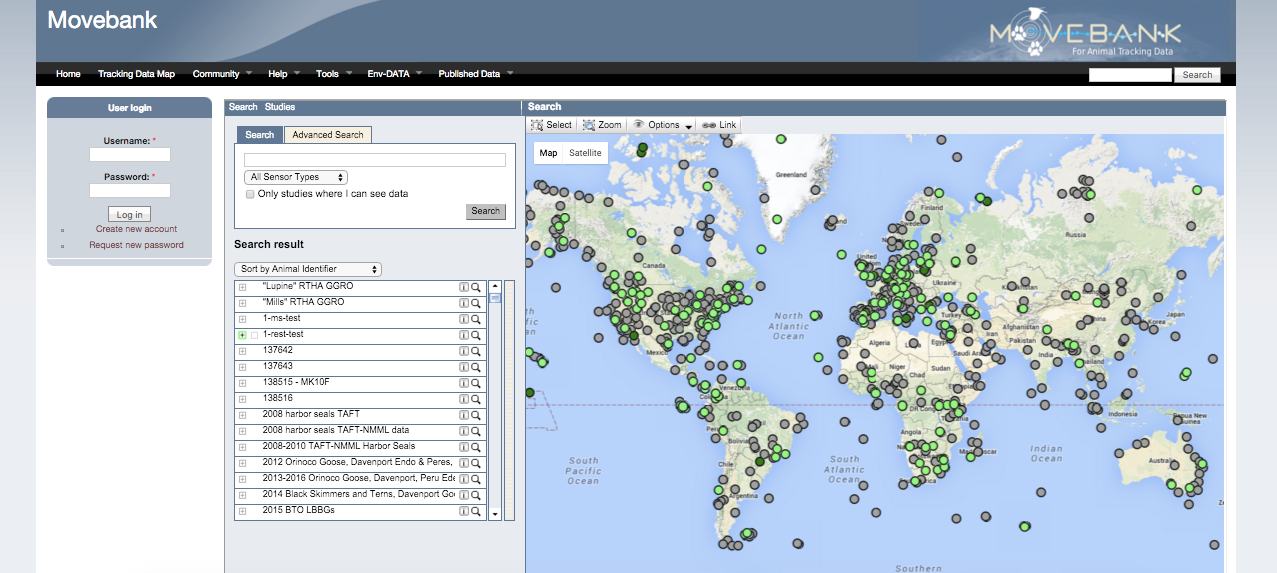

It made sense to house all the information in one place, and this is where the idea for Movebank, a first-of-its-kind experiment in animal-powered data, was born. Kays and his co-founders debuted the site in 2008. It is maintained, hosted and largely funded by the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany. It’s free for researchers to keep, organize and share data that they can either upload or stream directly to the site. Users can set their own privacy levels; making data available to everyone, no one, or a select few. (In some cases, such as research tracking the nesting spots of endangered birds, it could be dangerous to expose the data.)

So far Movebank is home to information from 2,040 studies, has 11,000 registered users, 217 million locations, and data for 499 species.

So, why does it matter to the average person where a zebra in Botswana wanders? Well, it might not on a singular scale, but on a grand one, animal movement reveals volumes.

It can tell us about our changing environment and even the spread of infectious disease. It has been suggested that animal tracking could help predict earthquakes. Eventually, according to researchers, the use of animals as “naturally evolved sensors of the environment has the potential to help us monitor the planet in completely new ways.”

Currently, the data being corralled by Movebank is helping to unlock the mystery of bird migration—scientists have long supposed that birds might follow established “flyways” during migration, but it was difficult to suss this out, since most studies focus on one species. Movebank allows researchers to combine data on multiple species. The project also recently released a mobile app that lets users locate animals near them. For instance, a group of storks that Kays was monitoring recently took wing from North Carolina to Florida.

The map on the website movebank,org. (Photo: Courtesy Movebank)

“I don’t have time to go to Florida right now and look for them,” says Kays. “But if someone in Florida wants to go find them and tell us what they’re eating or if they’re with other storks, that could be really interesting.”

Of course, there are some things that technology cannot streamline.

In order to track animals, they must still be tagged and outfitted with any number of contraptions—some wear backpacks, others collars. Sometimes researches have to get creative. On the Movebank forum, a researcher asked for tips on what kind of glue to use on a pygmy hippo. Kays related a story about a colleague who was using something like a very tiny whale harpoon to tag regular-sized hippos. Raccoons are easy to catch, he says, toucans are not. The worst, he says, was being pinched by an anteater, an animal that has no teeth but formidable claws and is also challenging to tag.

“Their neck is bigger than their head,” says Kays. “So we couldn’t give them a collar, and we tried a harness and that didn’t work very well, so we glued it on their butt and that worked for a little while.”

Entertaining stories aside, the health and safety of the animal is always the main concern, says Kays, which is part of the reason miniaturization is a top priority in the animal tracking world. This is part of the reason Movebank co-founder Martin Wilkelski is spearheading a project to mount an animal tracking antenna on the International Space Station—its proximity to earth means that it takes less energy to beam data there and back, and that means smaller tags for smaller animals.

A deer mouse gets a 1g radio-tracking collar as part of a study of the effects of lyme disease on mouse populations. (Photo: Roland Kays)

In the long-term, animal big data should be a win-win for people and creatures.

“So many studies these days are all about learning about how animals are responding to humans,” says Kays. “Humans are taking over more of the planet and we’re trying to find ways for animals and humans to live together and minimize our impact on the animals.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook