Tracing the Circulatory System Behind Antarctica’s Blood Falls

It’s deep, salty, and very cold.

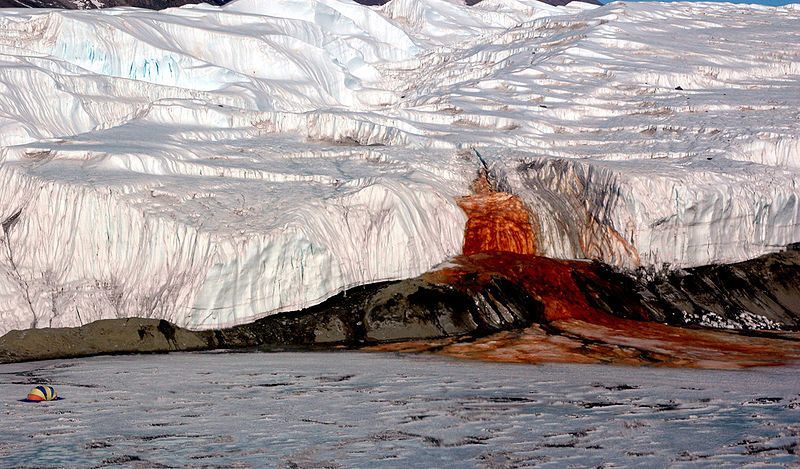

Blood Falls is an on-again-off-again flow of red-orange water—striking against Antarctica’s sweeping grayscape—from the toe of Taylor Glacier, not far from McMurdo Station research base. The color comes from iron in the salty water, which is thought to originate from a pocket of brine trapped deep beneath the glacier for more than a million years (and supporting its own, unique microbial ecosystem). But how that water gets through the glacier has been a mystery since the falls was first described in 1911.

Now a team from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Colorado College has used ice-penetrating radar to track the flow of red water almost 1,000 feet into the glacier. They encountered a circulatory system within, of brine pools and pathways, and now surmise that Blood Falls is a release valve for some of the pressures that emerge over 34 miles of slow-moving ice.

Blood Falls is also a special case, because the Taylor Glacier is so cold that it really shouldn’t have any liquid water flowing through it at all. In this case, the scientists found, the saltiness of the water (which lowers the freezing temperature) and the latent heat of freezing—which is definitely a thing—helps explain how Blood Falls keeps flowing.

“While it sounds counterintuitive, water releases heat as it freezes, and that heat warms the surrounding colder ice,” said University of Alaska Fairbanks glaciologist Erin Pettit in a statement. “Taylor Glacier is now the coldest known glacier to have persistently flowing water.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook