Audubon Made Up at Least 28 Fake Species to Prank a Rival

The prank’s full extent—11 fake fish, 3 fake snails, 2 fake birds, 1 fake mollusk, 2 fake plants, and 9 fake rats—is only now clear.

Pranks are meant to be discovered—what’s the point in fooling someone if they never notice they’ve been fooled? But one 19th century prank, sprung by John James Audubon on another naturalist, was so extensive and so well executed that its full scope is only now coming to light.

The prank began when the French naturalist Constantine Rafinesque sought out Audubon on a journey down the Ohio River in 1818. Audubon was years away from publishing The Birds of America, but even then he was known among colleagues for his ornithological drawings. Rafinesque was on the hunt for new species—plants in particular—and he imagined that Audubon might have unwittingly included some unnamed specimens in his sketches.

Rafinesque was an extremely enthusiastic namer of species: during his career as a naturalist, he named 2,700 plant genera and 6,700 species, approximately. He was self-taught, and the letter of introduction he handed to Audubon described him as “an odd fish.” When they met, Audubon noted, Rafinesque was wearing a “long loose coat…stained all over with the juice of plants,” a waistcoat “with enormous pockets,” and a very long beard. Rafinesque was not known for his social graces; as John Jeremiah Sullivan writes, Audubon is the “only person on record” as actually liking him.

During their visit, though, Audubon fed Rafinesque descriptions of American creatures, including 11 species of fish that never really existed. Rafinesque duly jotted them down in his notebook and later proffered those descriptions as evidence of new species. For 50 or so years, those 11 fish remained in the scientific record as real species, despite their very unusual features, including bulletproof (!) scales.

By the 1870s, the truth about the fish had been discovered. But the fish were only part of Audubon’s prank. In a new paper in the Archives of Natural History, Neal Woodman, a curator at Smithsonian’s natural history museum, details its fuller extent: Audubon also fabricated at least two birds, a “trivalved” brachiopod, three snails, two plants, and nine wild rats, all of which Rafinesque accepted as real.

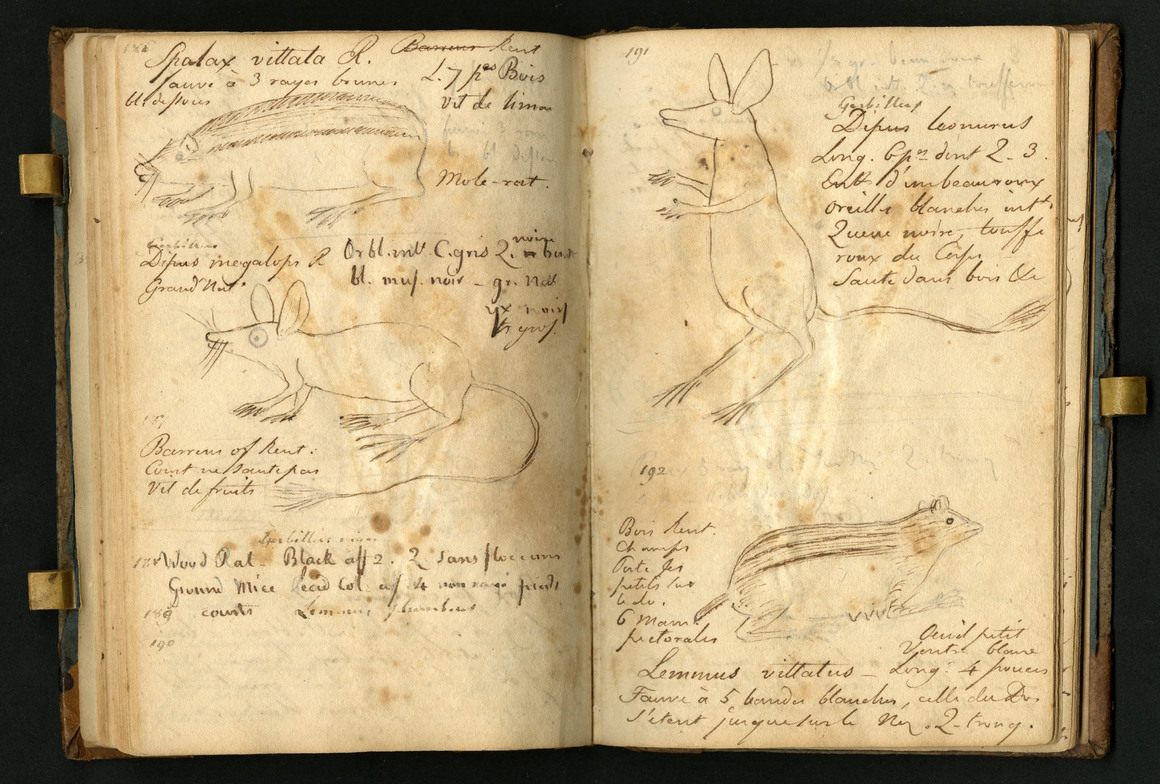

Woodman has been systematically checking through Rafinesque’s work in mammalogy. A mammalogist himself, he first started wondering about Rafinesque’s accuracy when he found that a shrew Rafinesque had identified was, in fact, a jumping mouse. One of Woodman’s long term goals is to try to identify the actual species Rafinesque was describing.

When he figured out that Rafinesque had also been naming mammals based on his time with Audubon, he started worrying.

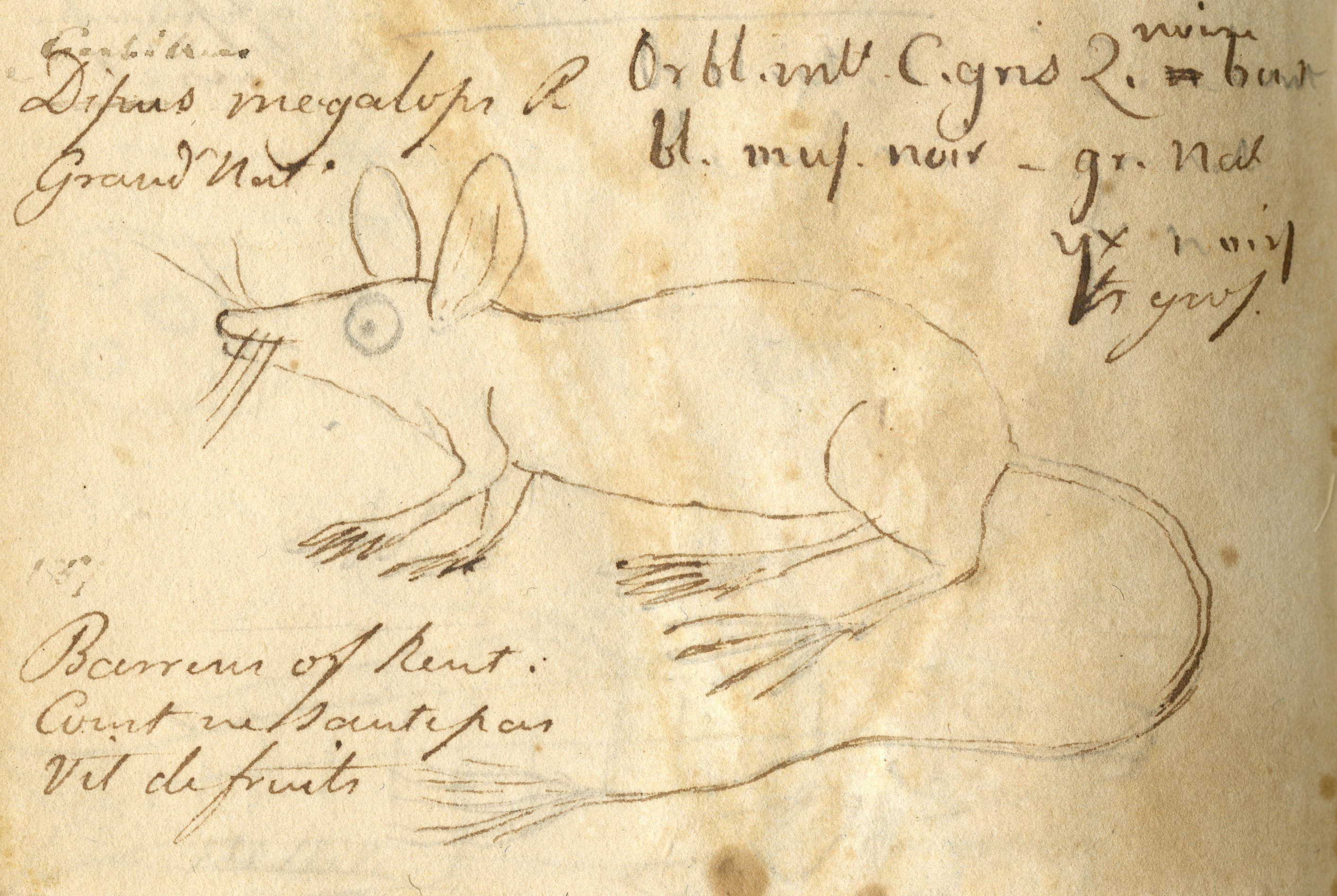

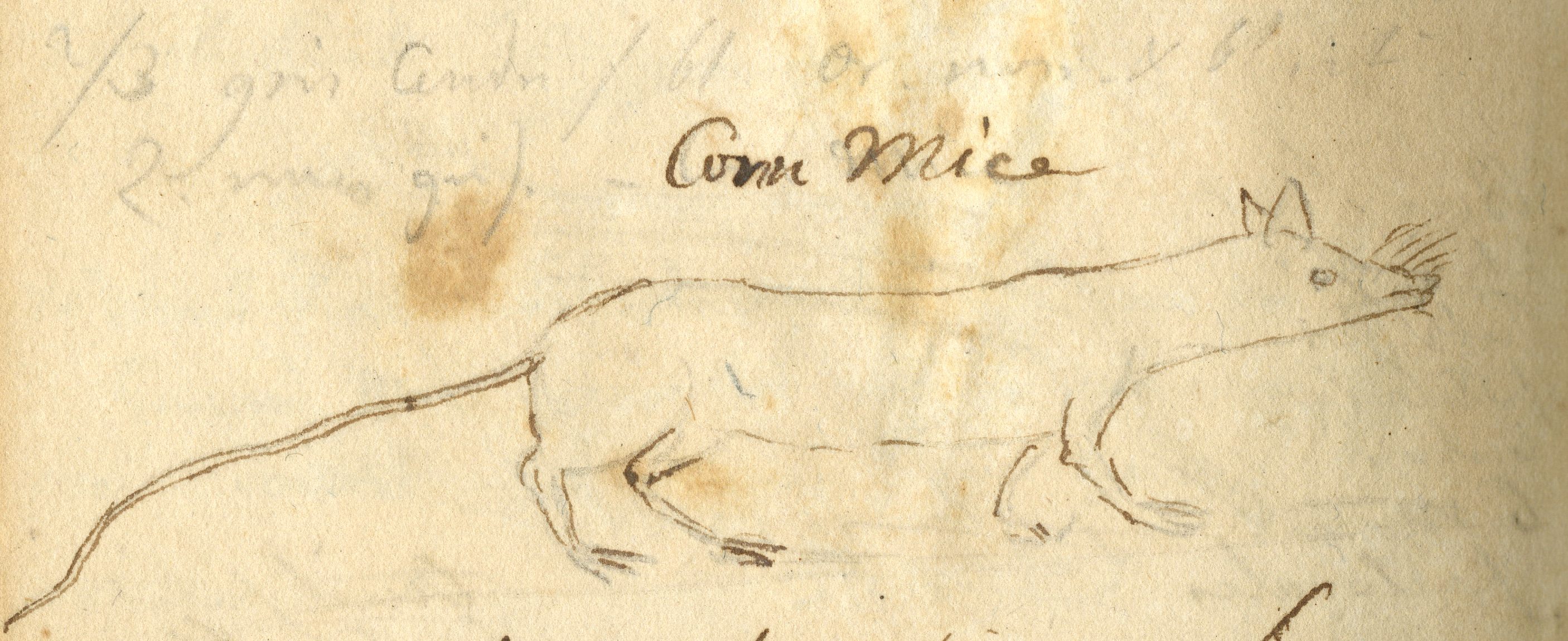

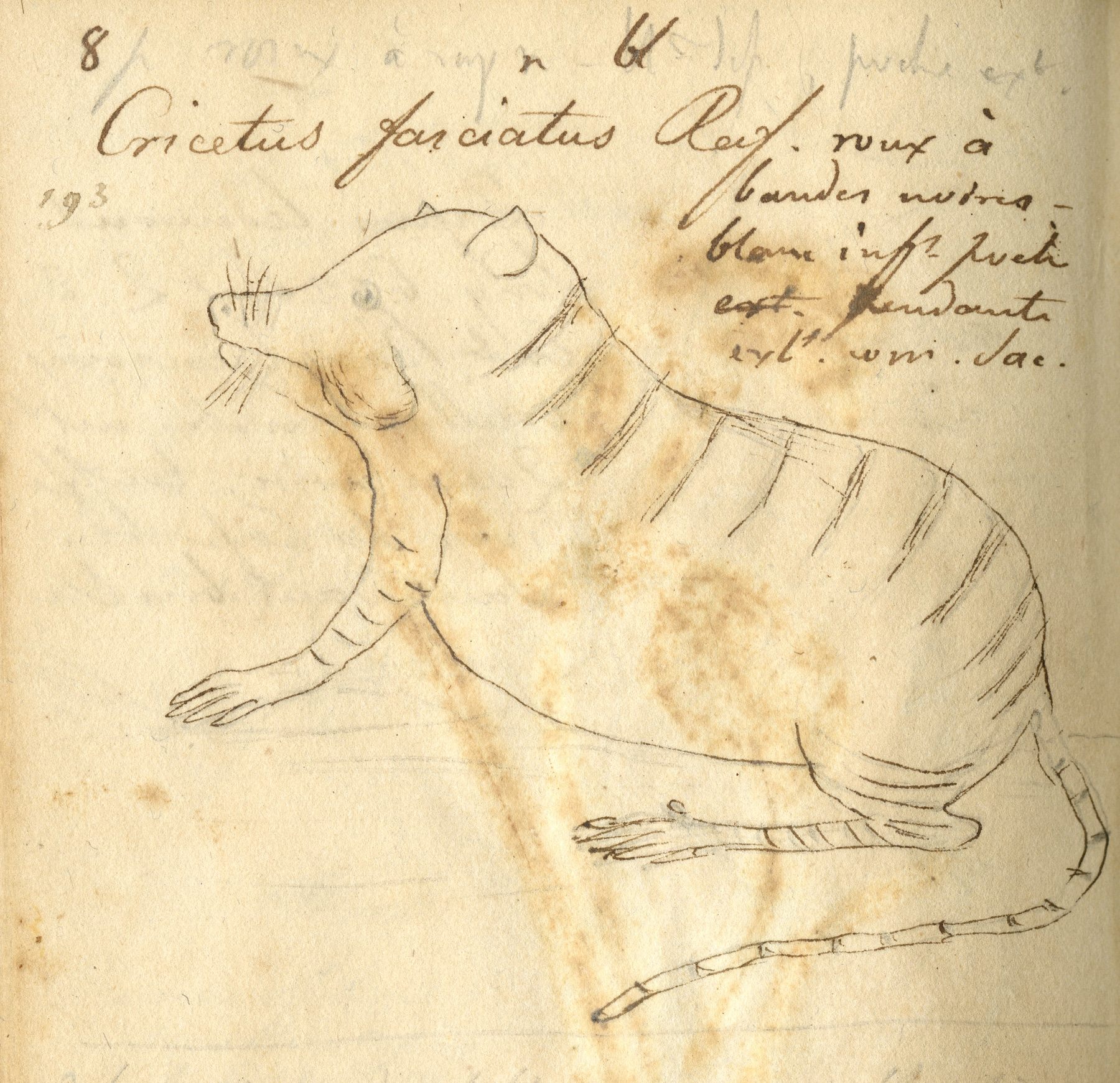

In his field journals from that period, Rafinesque describes ten “wild rats.” They included:

A “big-eye jumping mouse”

Not real.

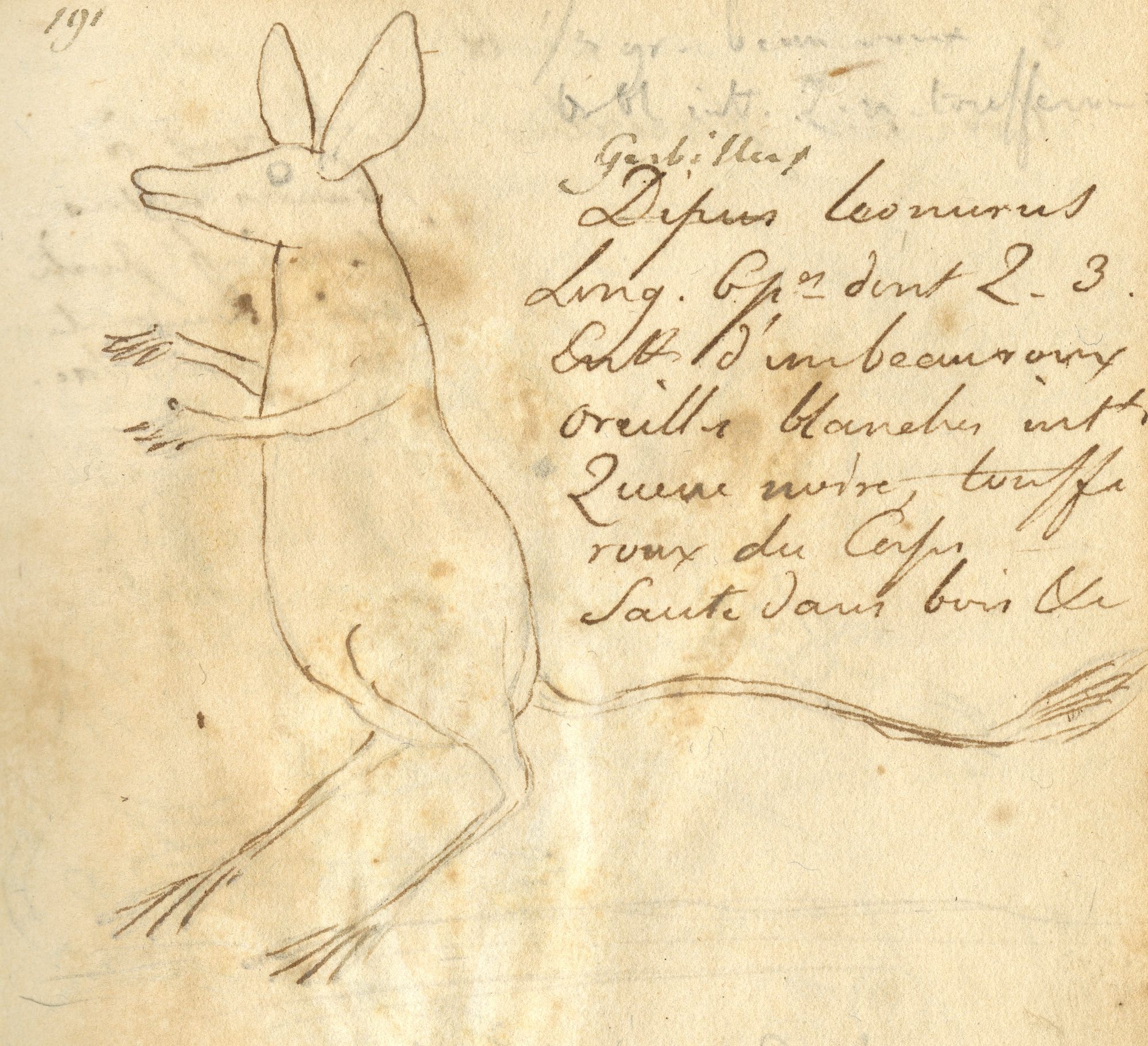

A “lion-tail jumping mouse”

Also not real.

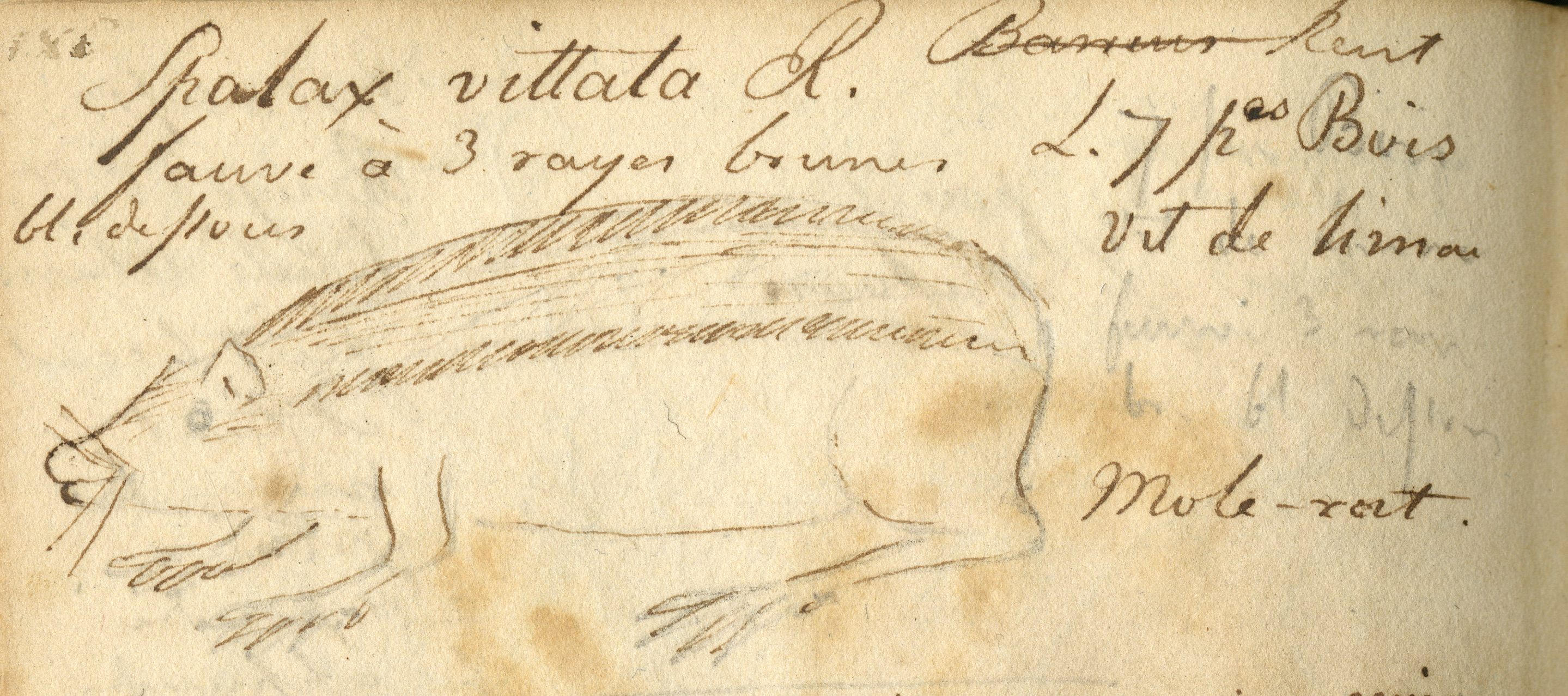

a “three-striped mole rat”

You get the idea.

a “black-eared shrew”

Hm.

And a “brindled stamiter.”

Cheek pouches on the outside.

In the descriptions Audubon gave to Rafinesque, some of these animals had very odd features. The “three-striped mole rat” was attributed to a genus that had no business being in North America. The “white-stripe lemming” carried its young on its back, despite have teats on its chest. The brindled stamiter had its cheek pouches, usually an interior feature, on the outside.

Rafinesque did worry a little bit about the information Audubon was giving him, Woodman reports—but only about the accuracy of small details. He never seemed to suspect that the species might not exist at all.

At this point in taxonomic history, no one’s relying on Rafinesque’s identifications for real information. The point of uncovering the prank, says Woodman, is that credit should go where credit is due.

“People have blamed Rafinesque for making species up himself,” he says. “They refer to Rafinesque’s fertile imagination.” But it was Audubon’s imagination they should have been crediting all along.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook