The Mysterious Tree Carvings of America’s Basque Sheepherders

Arborglyphs document a lonely life out West.

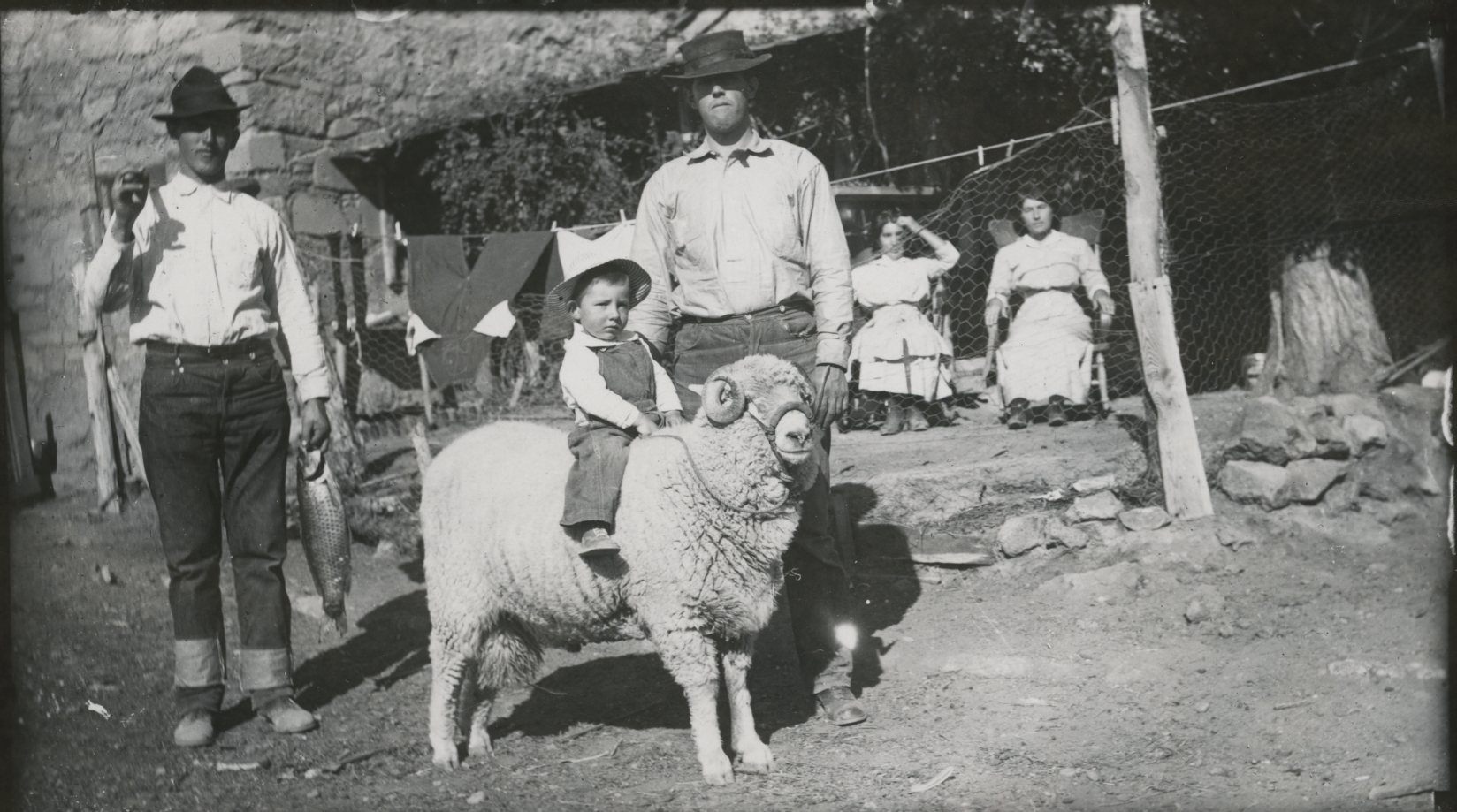

Some Americans, to learn about their ancestors, can dig through documents detailing when they passed through Ellis Island or flew in or got married, or where they lived at the time of a census. But for some Basque families in the United States, the only record they have of their immigrant ancestors is carved into trees in secluded aspen groves throughout the West. Names, dates, hometowns, and other messages and art scar the pale bark of aspens where Basque men watched over herds of hundreds of sheep from the 1850s to the 1930s.

The Basque are a genetically and linguistically distinct people from a region of the western Pyrenees straddling France and Spain. They speak Euskara and are believed to be the oldest indigenous group in Europe. Many came to the United States in the 19th century in search of opportunity—often in the form of gold or jobs—and ended up in parts of the Great Basin—Southeastern Oregon, central Idaho, and Nevada. Some started ranches, while others found themselves in sagebrush-covered hills and mountains, alone but for hundreds of sheep, a donkey, and some dogs to keep them company.

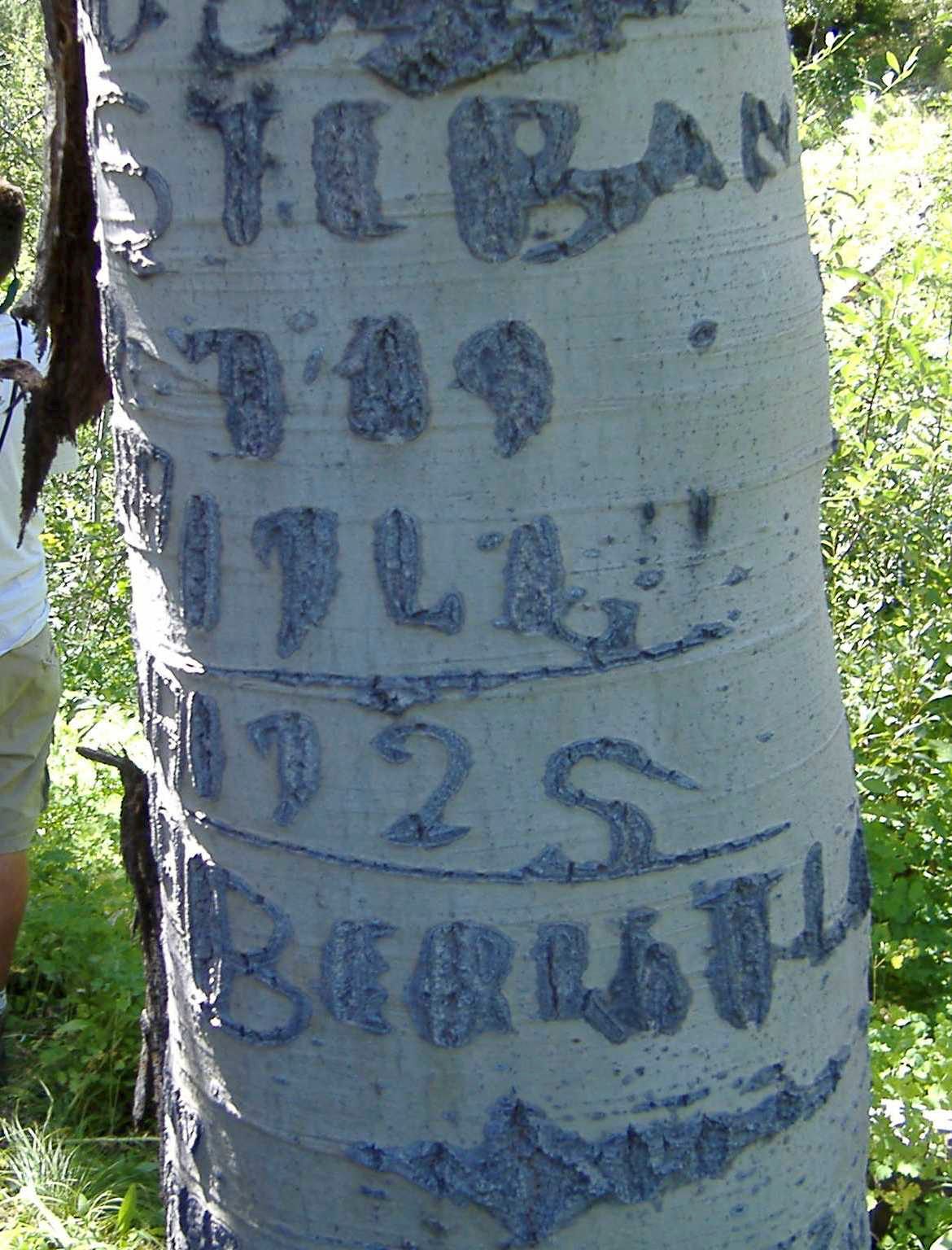

“This is a pretty anonymous group,” says John Bieter, a Basque historian at Boise State University in Idaho. For many of them, there aren’t records of them emigrating from Europe or entering the country, or employment records detailing where they were taking on sheep. But they did make tree carvings, known as arborglyphs, which are often found near campsites or rest stops where the herders and their charges would spend the hottest hours of the summer days. The biographical information they carved with knives now allow researchers and descendants to track their movements around the West. “It’s about as close as a documentation trail as you’re going to get,” says Bieter.

Herders often returned to the same places, year after year, and updated the trees they had signed, which has created a record of cultural shifts. “When you track herders over time, you find Americanizing influences,” says Bieter. The first time they signed, for example, many used a Spanish or Basque spelling and a European date format, with the date first and month second. But later arborglyphs show that some herders changed the date format and how they spelled their names—from Lorenzo to Lawrence, for example.

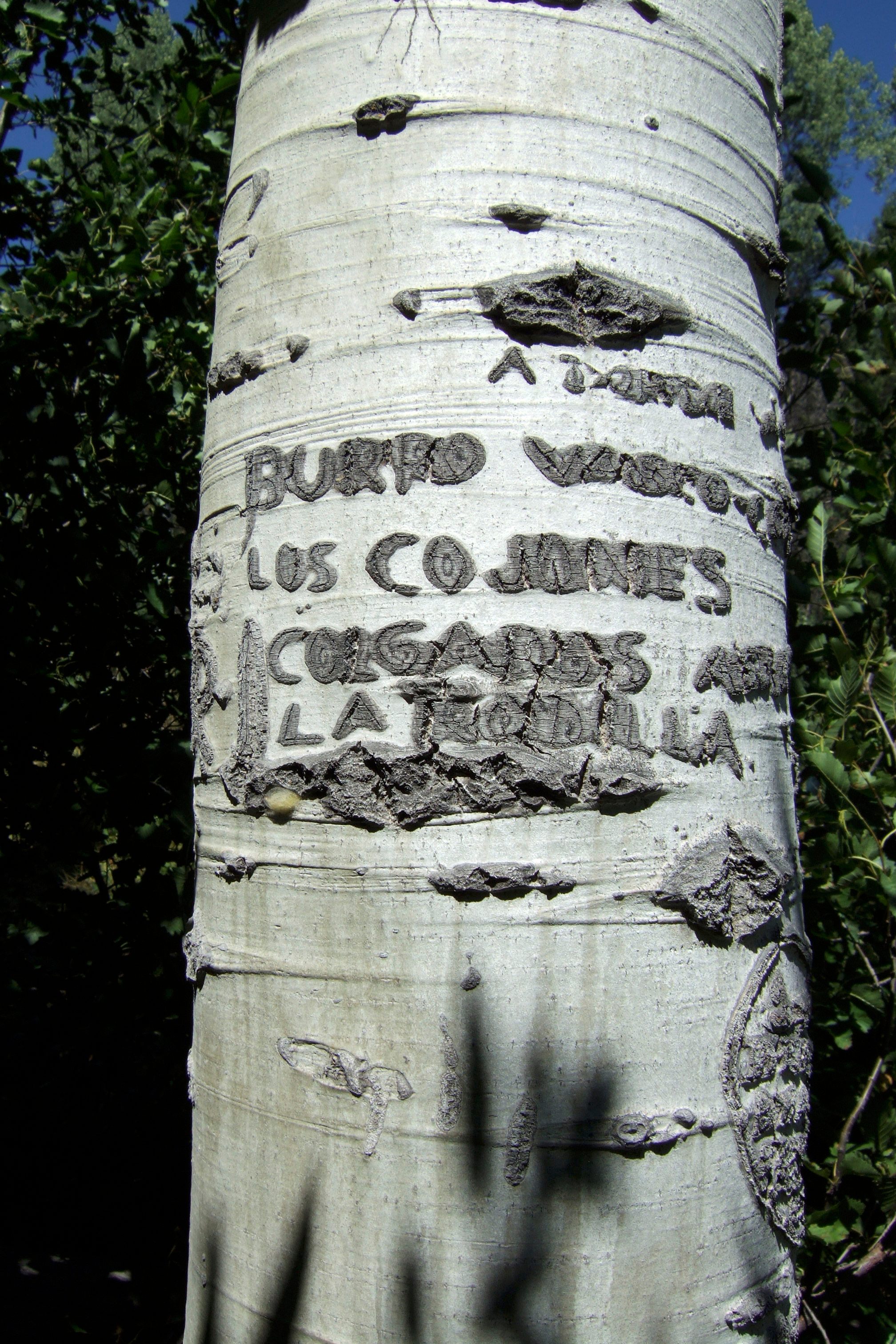

Some got a bit more creative. Certain arborglyphs include markers representing hometowns or favorite soccer teams. Others depict churches or farmhouses from back in Basque Country. Animals and fishing boats have also been found. One carver managed to fit part of a poem on a single tree. Other carvings feature naked women in a variety of positions—references to encounters with prostitutes, in some cases. “As you move later into the 20th century, you get a lot more political,” says Bieter. As tensions mounted between the Basques and the Spanish government, and when the Spanish Civil War broke out, sheepherders carved messages expressing support for Basque causes and their dislike for dictator Francisco Franco. Aspen trees are usually between three and 18 inches in diameter—with such a limited canvas, herders carved what was most important to them. What remains is a guide to how that changed over time.

Today it’s rare to find an arborglyph with a date from the 1800s. Aspen trees live for around 150 years under ideal conditions, and many of the earliest arborglyphs were carved on trees that have since died. “We’re trying to document as fast as we can the ones that are still remaining,” says Bieter. “What we’re trying to beat now is just time and fire.” Climate change is shortening the tree’s longevity, as extreme weather patterns and larger wildfires affect the regions where arborglyphs are found. Vandalism is also a concern—people have even cut down trees to steal particular works.

Thousands of these trees have been documented in Idaho, California, Oregon, and Nevada, and databases hosted by the University of Nevada, Reno and Boise State University contain photos, drawings, and transcriptions gathered by historians, forest archaeologists, and community groups. We may have already missed out on the first 50 years of Basque sheepherder history, but there’s still a chance to document what remains—a seemingly neverending task in a vast landscape dotted with the welcoming shade of aspens.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook