Battles, Batman, and Liberace: A Cultural History of Capes

Ever Wonder how capes came to be Thor-t of as superheroic? (Photo: randychiu on Flickr)

Simple in design, yet evocative of the utmost drama and intrigue, capes are sartorial shorthand for imminent action. To fasten one around your shoulders is to say to the world: “Some pretty major scenes are about to go down. And make no mistake: I am ready.”

It’s a message that comes across regardless of whether the wearer is a warrior, a superhero, or Liberace. But how did capes come to be imbued with excitement and peril? That’s a story that starts with the very etymology of the term ”cape.”

The Latin word for cape, cappa, forms the basis for the word “escape,” which comes from ex cappa. “To escape,” wrote Walter William Skeat in An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, “is to ex-cape oneself, to slip out of one’s cape and get away.”

From the early days of the cape, when Latin was still spoken on the streets, capes spoke of battle, status, and statuses in battle. Military commanders of the Roman Empire donned paludamentum—a long, flowing cape fastened at one shoulder—as part of their ceremonial battle preparations. Centurions fighting under their command got to wear capes, too, but had to settle for the sagum, a less majestic, less flowy version that fastened with a clasp across the shoulders.

Caesar and his cape-wearing cronies are unimpressed by this rider fellow in an 1898 painting by Lionel Royer. (Photo: Public domain)

Over the centuries, the cape and the sword came to be regarded as a package deal. In 1594, Italian fencing master Giacomo di Grasse penned a True Arte of Defence, in which he included several tips on vanquishing an enemy when armed with a sword-and-cloak combo. Wrapping one’s cloak around the non-sword-wielding arm helps shield it from blows, di Grasse wrote, but the cloak itself can also be used as a weapon:

“when one hath his cloake on his arme, and sword in his hand, the advantage that he getteth therby, besides the warding of blowes, for that hath bene declared in the true arte is, that he may molest his enimie by falsing to fling his cloake, and then to flinge it in deed”

This “flinging of the cloak” is an early appearance of the cape as a mantle fit for bouts of flouncing. To throw back the sides of a cloak, or toss one side of a cape over one’s shoulder, is a pleasingly dramatic way of revealing a weapon, showing one’s true identity, or punctuating a satisfying riposte, whether physical or verbal. These seeds of “cape as garment of flamboyance,” thus planted, would be harvested centuries later by cape aficionado Oscar Wilde, then augmented with glitter by performers like Liberace.

The practical approach of wearing a cape over one shoulder in order to keep one’s sword arm free became a fashion trend during the late 16th century, when gentlemen donned the ”mandilion,” a hip-length cloak with open side seams. Even when not engaged in a duel with a no-good roister-doister, men wore their mandilions slung casually on one shoulder to look cool.

Robert Devereaux, Second Earl of Essex, being all casual-like circa 1596. (Image: National Gallery of Fine Art/Public domain)

The cape as the preferred outerwear of adventurers gained ground with the dashing swashbuckler archetype, first established in literature of the 16th century but most popular during the mid-19th- to early 20th centuries. Many of the protagonists belonging to the genre were known to throw on a cape, grab a sword, and head for the forests in search of mischief. Among characters who couldn’t spell “caper” without a cape were The Three Musketeers, Cyrano de Bergerac, The Scarlet Pimpernel, and Zorro.

Amid all the suave rapier-waving and damsel-saving going on in the swashbuckler genre, a work of literature emerged that dragged the cape into the world of the macabre and the supernatural: Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Written in 1897, Stoker’s version of the eponymous Count did not, however, feature the high-collared, black and red cape to which pop culture is now accustomed. The only mention of Dracula’s outerwear in the book is this line from chapter three, in which the Count’s startled estate agent, Jonathan Harker, describes his client scuttling down an exterior wall of the creepy manse he’s been tasked with selling:

“I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over that dreadful abyss, face down with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings”

The iconic Dracula cape now inextricably linked with the character was not established until the 1920s, when adaptations of Dracula hit the stage. And the cloak revamp had more to do with budgetary concerns and theatrical trickery than aesthetics, according to Jonathan Bignell in “A Taste of the Gothic: Film and Television Versions of Dracula”:

“Stage versions of the novel needed to have Dracula on stage in drawing-room settings, rather than appearing rarely and in a wide range of outside locations as in the novel. The need to turn Dracula into a melodramatic tale of mystery taking place indoors was the reason for the costuming of Dracula in evening dress and opera cloak, making him look like the sinister hypnotists, seducers and evil aristocrats of the Victorian popular theatre.

“The high-collared cape which we now recognize as a hallmark of the Dracula character was first used in the stage versions. Its function was to hide the back of the actor’s head as he escaped through concealed panels in the set to disappear from the stage, while the other actors were left holding his suddenly empty cloak.”

This practical costume change had a huge cultural impact. Bela Lugosi, who portrayed Count Dracula in 1920s stage adaptations and the 1931 Dracula film, became synonymous with the character in the cape—to the point that, when he died, he was shrouded in one of his Dracula cloaks before being placed in a coffin.

Bela Lugosi in the 1931 film adaptation of Dracula. (Photo: Fair use)

Bela Lugosi in the 1931 film adaptation of Dracula. (Photo: Fair use)

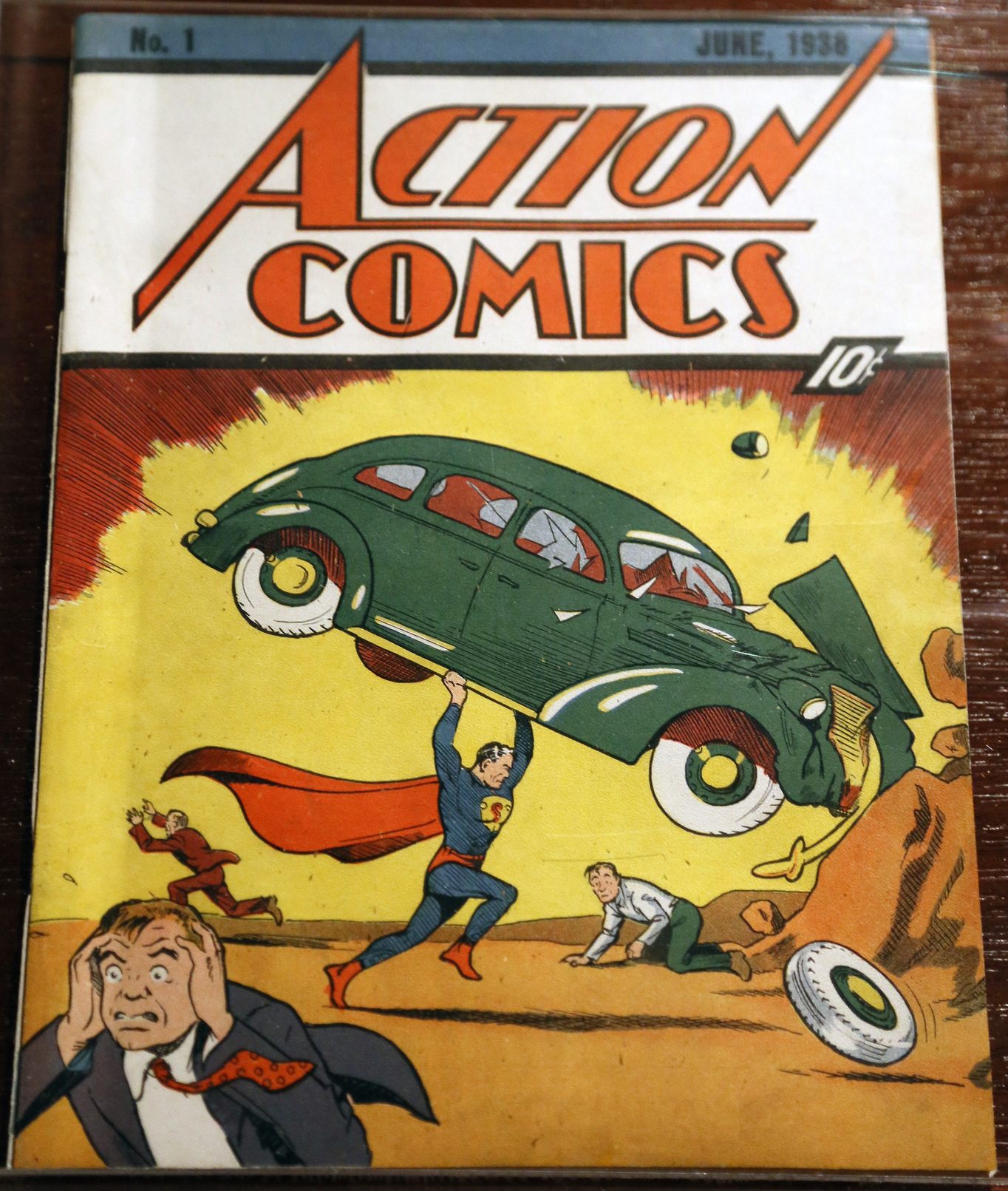

The cape as a harbinger of impending violence and melodrama finds its ultimate expression, of course, in another major archetype: the superhero. Superman, the first comic-book superhero, rocketed into American culture in 1938 with an appearance on the cover of Action Comics #1. Depicted lifting a green car above his head in the presence of three astonished onlookers, Superman wears a long, red cape that flows gloriously in the wind as he displays his superhuman strength and steely approach to calamity prevention.

A year after Superman’s debut, Batman was introduced to the world in Detective Comics #27, sporting an even bigger cape—a billowing, swirling, ankle-length black version with a scalloped hem that alluded to the dramatic wings of his animal namesake. The designs of these two pioneering superheroes created a blueprint for all the comic book heroes that would follow in their belted-and-booted wake.

Superman, blowing minds during his inaugural appearance in 1938. (Photo: Jim, the Photographer/Creative Commons)

“More than anything else, cape says superhero,” says Daniel Kibblesmith, a long-time comic book fan, co-writer of upcoming Heavy Metal comic The Doorman, and writer for The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. “Capes are an indicator of self-awareness. I think a superhero who puts on a cape in 2015 is sort of doing an impression of Superman or Batman, whether they mean to or not.”

This evocation of the classics can have positive or negative effects. While a cape is now shorthand for action, its association with the aesthetics of the early superheroes—and the campy, low-budget ’60s TV versions of Batman and Robin—can be a hindrance for 21st-century characters who need to look as dogged and bad-ass as possible.

Burt Ward and Adam West as Robin and Batman in the cape-swinging ’60s. (Photo: Public domain)

“The old-timey, inaugural characters all wore capes, and then whenever they upgraded a character, one of the first things they did was get rid of the cape,” says Kibblesmith. In 1984, when Robin outgrew his role as Batman’s sidekick, he transformed into a new hero, known as Nightwing. In his new, more grown-up guise, the character formerly known as Robin sported a dark, tight-fitting suit and no cape.

As evinced by fashion designer Edna in Pixar’s The Incredibles, capes can get snagged on a missile fin or caught in a jet turbine, turning a heroic moment into a needlessly fatal one. Wonder Woman, who was introduced to the comic book world in 1941, avoids such mishaps by restricting her cape-wearing to special occasions or formal events, such as when acting as an ambassador on behalf of her home nation, Themyscira. When Lynda Carter played the character during the 1970s, the cape didn’t appear often, but when it did, it was accompanied by a bow-chicka-bow-wow soundtrack:

But what does it mean when a character wears a cape these days?

“At Marvel, capes are worn almost exclusively by imperious characters with regal bearing,” says Alejandro Arbona, an Editor at Valiant Entertainment who, prior to his current job, spent five years working on superhero stories at Marvel. “Monarchs, gods, sorcerers, and self-important blowhards” are among those he categorizes as regal within the Marvel universe.

Smaller publishers like Image Comics have less discernible cape-wearing criteria. Take the character of Spawn, an anti-hero birthed in the 1990s whose attire precedes him.

“Spawn is more cape than man,” says Kibblesmith. “He is 90 percent cape.”

A cosplayer exhibits a modest, pared-down version of the Spawn cape. (Photo: Clavo beta/Creative Commons)

A murderer of innocents who returns to Earth after being cast into the depths of hell, Spawn exemplifies the conundrum of the cape: it is an odd confluence of traditional beat-‘em-up masculinity crossed with campy theatricality, with a dose of the macabre thrown in for good measure. Given their history, capes can’t help but come off as a little ridiculous—but in a winking, self-aware, “Hey, I’m going to own this” way.

When Liberace played Radio City Music Hall for two weeks in 1984, he went all out in the cape stakes. In a feature on the eve of the engagement, the New York Times gave a sneak peek of what to expect:

“He will make his entrance onstage in a custom-made Rolls covered with tiny silver mirrors, and step out wearing a $300,000 Norwegian blue fox cape trailing a 16-foot train studded with bands of Austrian rhinestones.

Before playing his first number—on a matching piano covered with Austrian rhinestones, naturally—Liberace will summon a smaller Rolls to carry off the cape, which weighs 135 pounds. (Two of Liberace’s costume attendants have already been operated on for hernias developed while handling the star’s wardrobe.)”

Some of Liberace’s many extravagant capes at the now-closed Liberace Museum in Paradise, Nevada. (Photo: Julia on Flickr/Creative Commons)

Some of Liberace’s many extravagant capes at the now-closed Liberace Museum in Paradise, Nevada. (Photo: Julia on Flickr/Creative Commons)

The sheer, excessive silliness of all that speaks to a tantalizing promise that capes offer: put me on, and the normal rules no longer apply.

Surprisingly, this principle translates to a civilian context. At Brooklyn’s Superhero Supply Store, offerings include a range of brightly colored capes and a “cape tester,” a platform equipped with a fan angled upward to create a brisk wind. Shoppers are invited to try on a cape, climb the stairs to the platform, and see how the garment billows in the breeze. Joshua Mandelbaum, Executive Director of 826NYC, the education non-profit that runs the Superhero Supply Store, says that anyone who tries it automatically behaves as though “they’re in the presence of something heroic.”

“Once you’re up on the cape tester, the first thing you do is put your fist on your side and you strike that pose, or you turn to the side and you put your hands out as if you’re flying,” he says.

And it’s not just kids who react that way. “I am always surprised by how many adult capes we sell. So much so that I am surprised I don’t come across more grown-ups wandering around Brooklyn in capes, because I have no idea what happens to them all when they leave the shop.”

The cape tester at the Superhero Supply Store. (Photo: Alex Erde on Flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook