Before Radios, Pilots Navigated by Giant Concrete Arrows

The remnants of Transcontinental Air Mail Route Beacon 37A, which was located atop a bluff in St. George, Utah. (Photo: Dppowell/Wikipedia)

The remnants of Transcontinental Air Mail Route Beacon 37A, which was located atop a bluff in St. George, Utah. (Photo: Dppowell/Wikipedia)

Across the United States, from Los Angeles to New York, lies a network of mostly forgotten infrastructure, a system that was obsolete before it was ever finished—forgotten relics from the early days of powered flight.

The early 20th century was an era of American history where Manifest Destiny seemed, well, manifest. The West had been won, and the cities blossomed. But with innovation came change and obsolescence. Trains became the prime movers of not only people and goods, but also the mail. The Pony Express proved the value of a trans-continental postal system in the United States, but the service was quickly usurped—the completion of the telegraph lines from East to West in 1861 saw it go out of business after just 18 months.

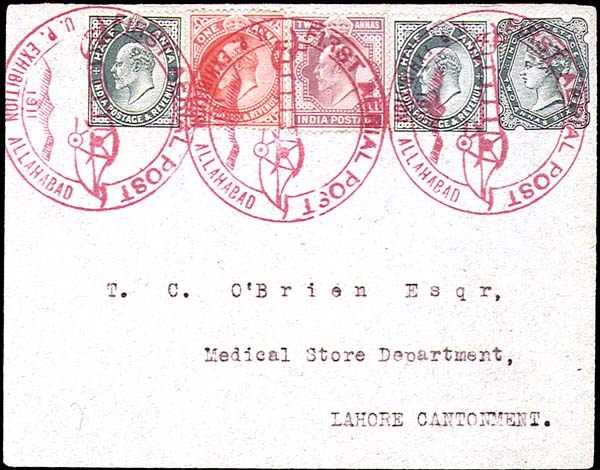

Our modern style of mail delivery, air mail, debuted less than eight years after powered flight. In 1903, the Wright brothers launched their Flyer at Kitty Hawk in 1903. On February 17, 1911, Fred Wiseman, an amateur pilot, carried three letters from Petaluma, California, to Santa Rosa, California, 18 miles away. The very next day, Henri Pequet delivered 6,500 letters from Allahabad, in northern India, to the city of Naini, located around eight miles away.

A letter that traveled on the 1911 flight from Allahabad. (Photo: Public domain on Wikipedia)

In 1914, the first long-distance airmail delivery was achieved. Between July 16th and 18th, Maurice Guillaux carried mail 584 miles, from Melbourne to Sydney. But it wasn’t until 1918 that the east coast of the US got limited aerial postal deliveries. Two years later, the nation’s transcontinental air mail route, stretching from New York to San Francisco, was flown for the first time.

Air travel and aviation in general was a difficult affair during the early twentieth century. Before the development of radio navigation, the primary method of flying across the United States was to travel along the rail routes, or “following the iron compass,” as they called it at the time. As the railways usually connected population centers, they became the easiest way to navigate between cities and towns. But there needed to be other options.

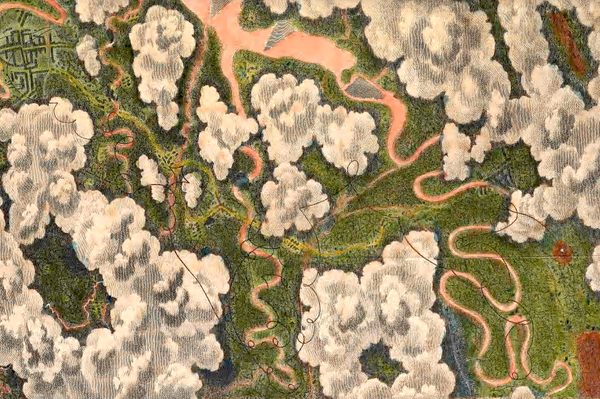

Part of the solution was to establish concrete arrows, painted a brilliant yellow and embedded alongside 50-foot-high lighthouses (referred to in the aviation community as beacons) that shone out a route of light across the continental United States. Measuring up to 70 feet long, the arrows pointed in the direction of the next beacon-and-arrow, and were visible from a distance of 10 miles up.

An airway beacon in St. Paul, Minnesota, built in 1929. (Photo: McGhiever on Wikipedia)

An airway beacon in St. Paul, Minnesota, built in 1929. (Photo: McGhiever on Wikipedia)

Before the beacons were put in place the mail-planes would land, and transfer their deliveries onto trains to travel overnight—reminiscent of the horse-and-rider swaps on the Pony Express. The beacons solved the problems associated with flying at night, but poor weather often led to the grounding of fleets and the mail being slowed. The beacons were, however, a huge step forward from the original approach: building huge bonfires next to airfields. (“Fatal accidents were routine” in those low-visibility times, notes the Federal Aviation Administration.)

With the development of radio navigation, the arrows and beacons started to become obsolete for the more sophisticated companies in the industry. At the same time, there was an explosion of private aircraft owners. The equipment needed for radio navigation was often out of the price range of these flyers, and also the airfields where they were landing. Most pilots did not know how to use radio navigation in that era, anyway.

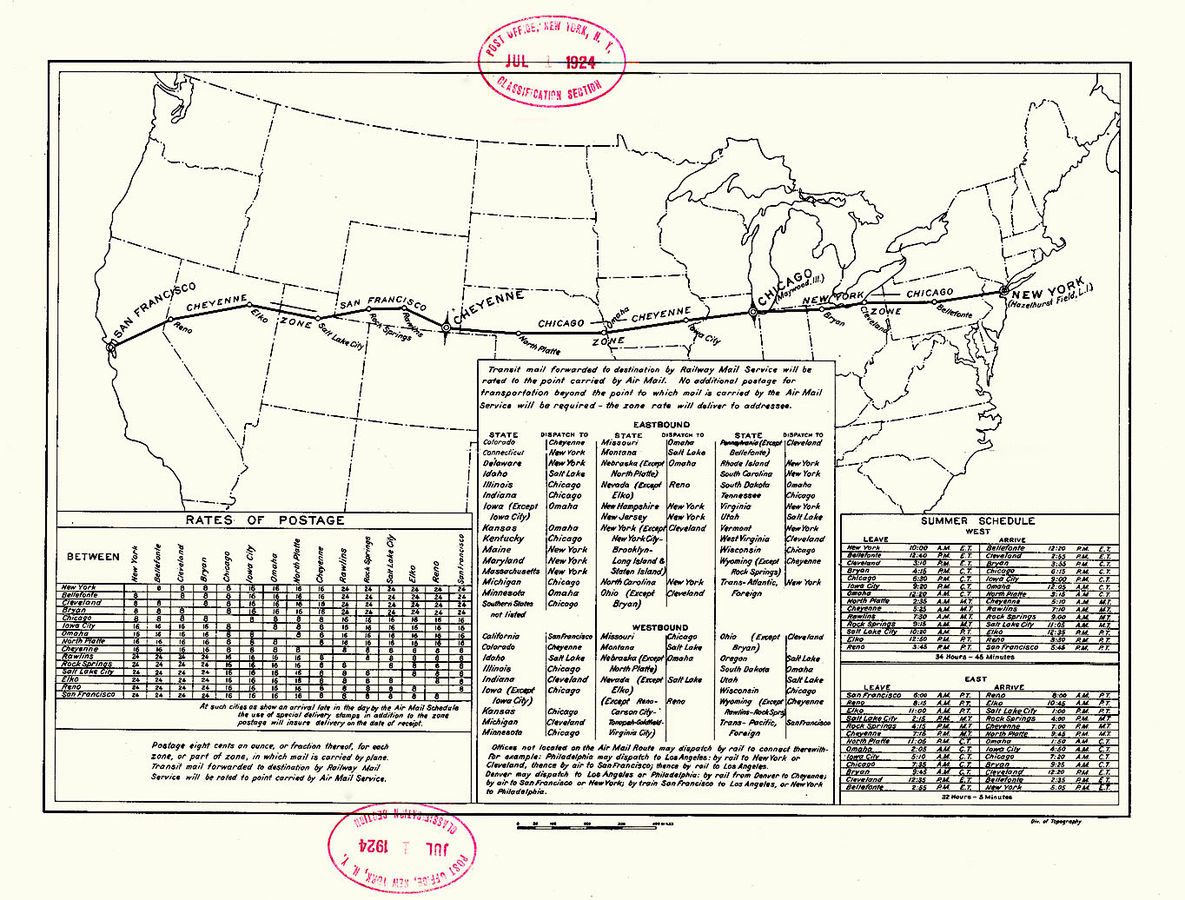

U.S. Post Office Department map of the First Transcontinental Air Mail Route. (Image: The Cooper Collection of Aero Postal History)

U.S. Post Office Department map of the First Transcontinental Air Mail Route. (Image: The Cooper Collection of Aero Postal History)

The arrow-and-beacon system proved incredibly popular with pilots, because not much could go wrong with giant concrete arrows on the ground. According to the Assistant Postmaster-General of the time, as quoted in the December 1923 issue of Popular Mechanics, there was a plan to build a similar system over the Atlantic. Yet, during the Second World War, the majority of the infrastructure was torn up, to stop the beacons from being used to provide directions to enemy bomber pilots. The metal used to build the towers was then redirected toward the war effort.

The concrete arrows, and some of the towers and sheds, still stand today. The state of Montana actually continues to use the system to help pilots navigate the rugged peaks of the region, as mountainous terrain can interfere with more sophisticated technological systems. Around nineteen of them are still in use. Here’s a handy map of some of the surviving locations of these nearly-obsolete stone aviation arrowheads.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook