Behind the Strange and Controversial Ritual When You Cross the Equator At Sea

U.S. sailors and Marines participate in a line-crossing ceremony. (Photo: Public domain/WikiCommons)

It starts at night. People hear a knock on their door and they know it has begun. From their ship’s berth, floating in the middle of the ocean, they are ushered into a room to begin the trial. They are being summoned into Neptune’s Court for crimes they’ve committed against the god.

The fun has just begun, and it’s going to continue for another 24 hours.

This is the beginning of a line-crossing ceremony, a centuries-old ritual to inaugurate Equator-crossing virgins. Ship passengers who have never traversed the nautical line are forced to prove they are worthy to make the transition.

The tradition began with the Navy over 400 years ago, says anthropology and sociology professor Carie Little Hersh in her 2002 paper “Crossing the Line: Sex, Power, Justice, and the U.S. Navy at the Equator.” Given its long history, the ritual has changed over the years, but it remains a well-known—albeit sometimes controversial—linchpin of Naval culture. But line-crossing has expanded to other corners of seafaring culture, including the unlikely place of scientific research cruises. Even commercial cruise lines have been known to host some parts of the ritual.

Though ceremonies differ, there’s a general form and a common cast of characters. King Neptune is a prominent figure, as is his representative Davy Jones. Other people often show up, including a surgeon, a barber, people dressed as bears, and a judge. These roles are all played by “shellbacks”—those who have gone through the ritual before. The first-time participants are known as “pollywogs”.

An illustration of an 1816 line-crossing ceremony aboard the frigate Méduse. (Photo: Public domain/WikiCommons)

While now it’s as much a spectacle as it is a test, the line-crossing ceremony reportedly has its roots in practicality. “It was designed to test the novices in the crew to see whether they could endure their first cruise at sea,” senior chief aviation boatswain’s mate Bernard Dizon told the Navy’s press office.

Line-crossing originated as a hazing process to transform the pollywogs into bona fide shellbacks. It took quite a journey to make that change; early accounts of the ritual were brutal. There were pageants where “wogs” were forced to crossdress in front of their superiors, and then spend the rest of their day performing often degrading tasks.

Professor Hersh described the proceedings of the ritual to me as an “inversion.” “While you are going through the ritual,” she explained, “you are constantly submissive.” In her paper she points to some examples where men were made to perform simulated sexual acts. Hersh’s research focused on how such an ingrained naval practice helped illustrate the power dynamics of people historically discriminated against in the Navy—namely gays and women.

This power asymmetry played a role in the ritual, showcasing innate naval biases. Those who were not favored fared worse. Hersh writes: “Pollywogs who are disliked, or who are suspected of being gay, receive especially harsh treatment, while favored wogs or high-ranking wogs are often pulled out of the ritual early, or are permitted to go through it without too much harassment.”

“Once you are initiated,” Hersh told me, “you are then in the masculine position… If you’re a woman that doesn’t make sense.” As the battle to include women on long-term Navy cruises ramped up—along with the campaign to end “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell”—so too began a huge backlash against the age old ceremony. The ‘90s saw large groups of people balking at its existence.

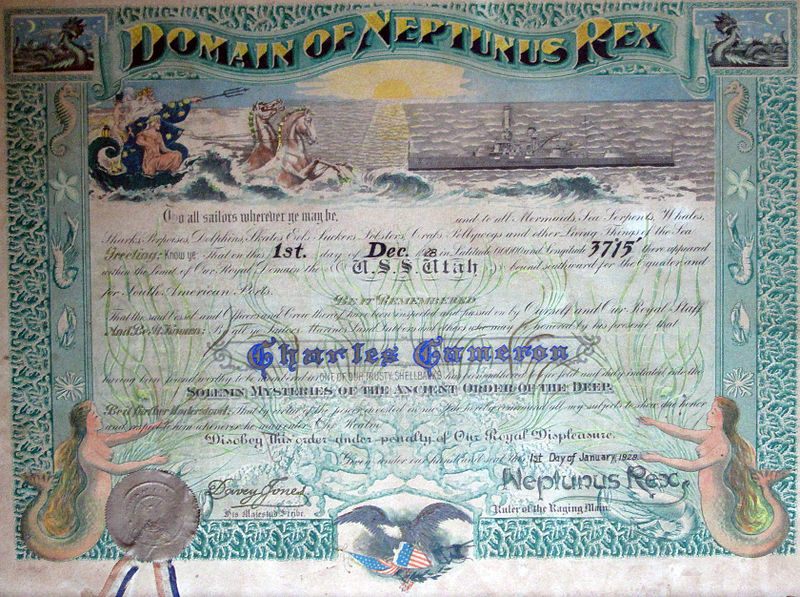

Shellback certificate awarded to Charles Cameron, aboard USS Utah (BB-31), commemorating his first crossing of the equator, December 1, 1928. This is typical of certificates awarded in the pre-WWII period. (Photo: Lou Sander/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Even so, the ritual has taken up other homes, albeit with distinctly less oppressive undertones. Most prominently, ocean scientists are known to perform similar ceremonies. Over the history of researchers hitting the high seas to acquire water samples and observe marine life, there are multiple accounts of ceremonies performed when the ships hit the Equator. Perhaps the most famous scientist to be initiated was Charles Darwin, who wrote about it in his diary. There are other similar ceremonies for different locales including the Arctic and Antarctic Circle, the International Date Line, and others.

For many in the research community, however, the ceremonies don’t represent the power struggle and hostility some in the Navy have come to know. “It’s kind of a nice tradition,” said one US-based ocean researcher when I asked her about her experience. She recalled the innovative costumes and how almost everyone on the ship was involved.

“I wouldn’t call it hazing per se,” the researcher said. In her experience, people were given the chance to opt out if they didn’t want to participate in the ritual. One person, in fact, did. As this scientist put it, everyone on the ship was fine with someone not participating; “No one egged her in her sleep.”

Neptune and his entourage during a Polish line-crossing ceremony. (Photo: Public domain/WikiCommons)

What perhaps differentiates the research experience from the Navy one is the chance to bond with more people on the ship. On Navy cruises everyone is considered a crew member, maintaining the ship in all ways needed. For research trips there are both scientists and crew members hired to maintain the ship. Normally there’s some separation between these groups, but during the line-crossing ceremony everyone is involved, be they scientist or crew. The researcher I spoke to remembered how on her trip two scientists were already in the order of shellback, so they joined the rest of the crew to help facilitate the day’s events.

The memory of the event sticks with people. Anyone inducted is quick to say they are part of this Order, but resistant to go into more detail. This is likely because of the bad rap the ceremony has accrued over the years. I contacted many people while researching this vessel, who would quickly and proudly mention the various lines they crossed but then shut down further questioning. “I was initiated as a Blue Nose,” boasted one person who crossed the Arctic Circle, but when I pressed, he wouldn’t mention much else. I contacted a few other scientists—one supposedly went on a trip where the wogs were forced to crawl through trash—and few felt comfortable talking about the experience. All the same, it’s not a secret. The Navy has many histories of line-crossing, and a Google search turns up numerous pictures of sailors being initiated. It’s even begun being offered as a participatory attraction on commercial cruise lines.

Perhaps the pride and secrecy stems from a desire to maintain the ritual unchanged. Hersh mentioned how the ceremony morphed as more people entered the Navy. For instance, blackface was a common element of it before World War II, but once integration hit the military that part stopped.

A Neptune party to celebrate crossing the equator, 1923. (Photo: The Field Museum Library/flickr)

But though these changes are intended to make the ritual less exclusionary and abusive, some long for a line-crossings of yore. For instance, as Naval backlash increased due to allegations of oppressive line-crossing practices, many officers dug in their heels and vehemently defended the ceremony, despite consequences to their own careers. The Navy has spent decades trying to rein in on hazing; the line-crossing ceremony represents a great deal of this. For a while, said Hersh, some boats tried to stop the ceremonies from even happening. Officers rebelled and did it anyway, which ultimately led to court martials.

One former Navy man posted videos of the ritual to YouTube. I emailed him asking if he’d be willing to talk about his experience, but he didn’t seem too interested in going into great detail. He concluded, “As far as I know they are still being performed but they are not as ‘fun’ as they used to be since all the politically correct people have ruined it.”

The scientist I spoke to was also proud of her line-crossing, describing it as “really positive.” But from her account, the experience seems to have been an inclusive, constructive one, fully compatible with what the Navy member called political correctness. Perhaps Neptune’s approval doesn’t depend on harassment.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook