Belgrade’s Modernist Masterpieces

A city’s distinctive architectural heritage.

The Western City Gate in Belgrade, Serbia, is a structure that demands attention. Consisting of two high-rises linked by a two-story walkway, it reaches 377 feet into the air and is topped by a small round tower. Enclosed concrete stairwells barrel up the sides like massive exhaust pipes. Also known as the Genex Tower, it was designed by Mihajlo Mitrović in 1977 and is currently the second-tallest building in the city. Unsurprisingly, it’s also on a new map that plots Belgrade’s Modernist architectural marvels.

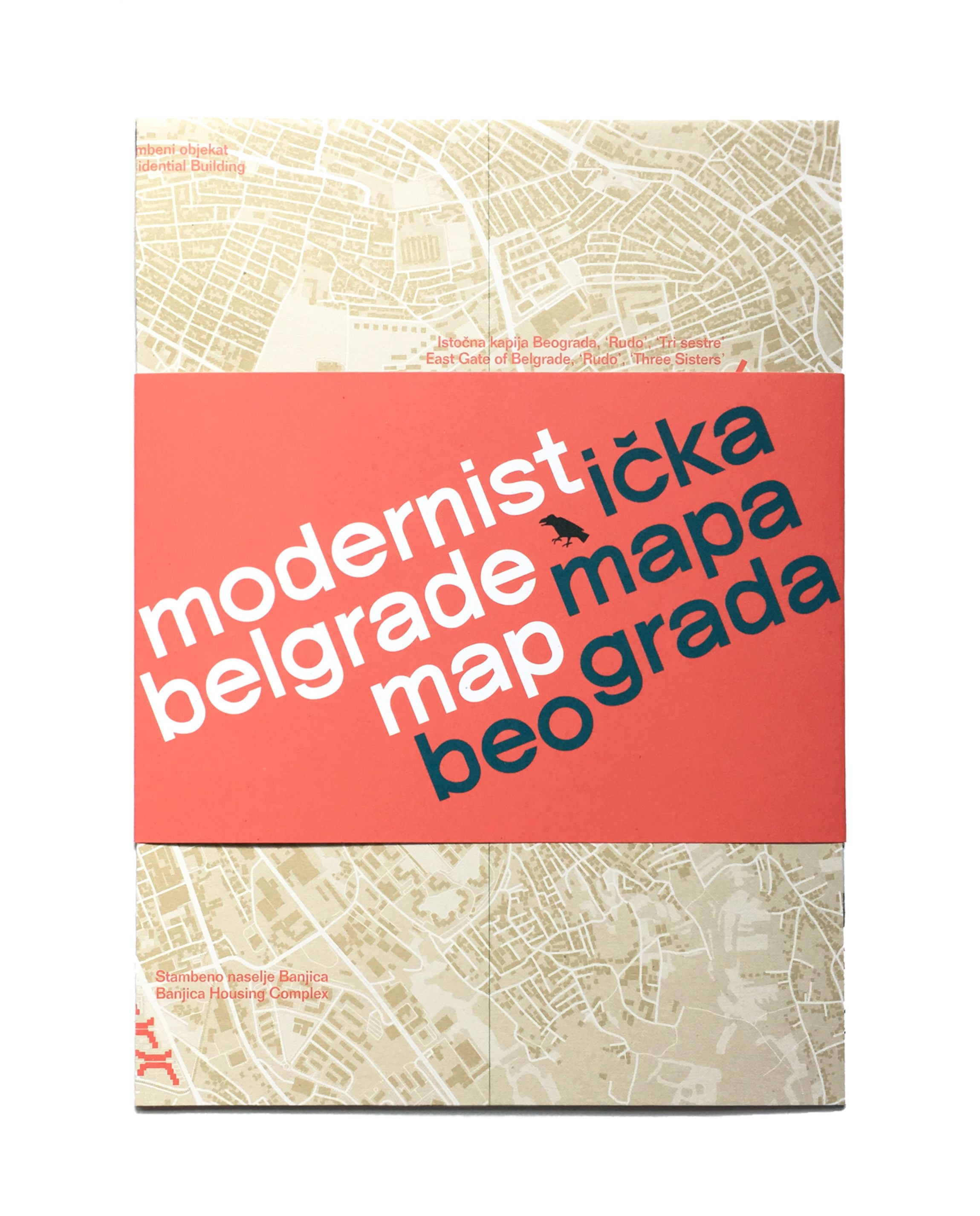

Modernist Belgrade, part of Blue Crow Media’s map series, highlights the city’s architectural heritage. After World War II, and after Yugoslavia split with the Soviet Union in 1948, a new part of the city, Novi Beograd (“New Belgrade”) was designated for development. “The postwar period went from industrialization to urbanization and modernization—a large number of schools, hospitals, public edifices, administrative buildings, all the way to roads, whole settlements, urban areas, and, finally, a huge amount of (proper and healthy) housing, was built in Yugoslavia, in the period of Modernism,” says architect Ljubica Slavković, who also edited the map.

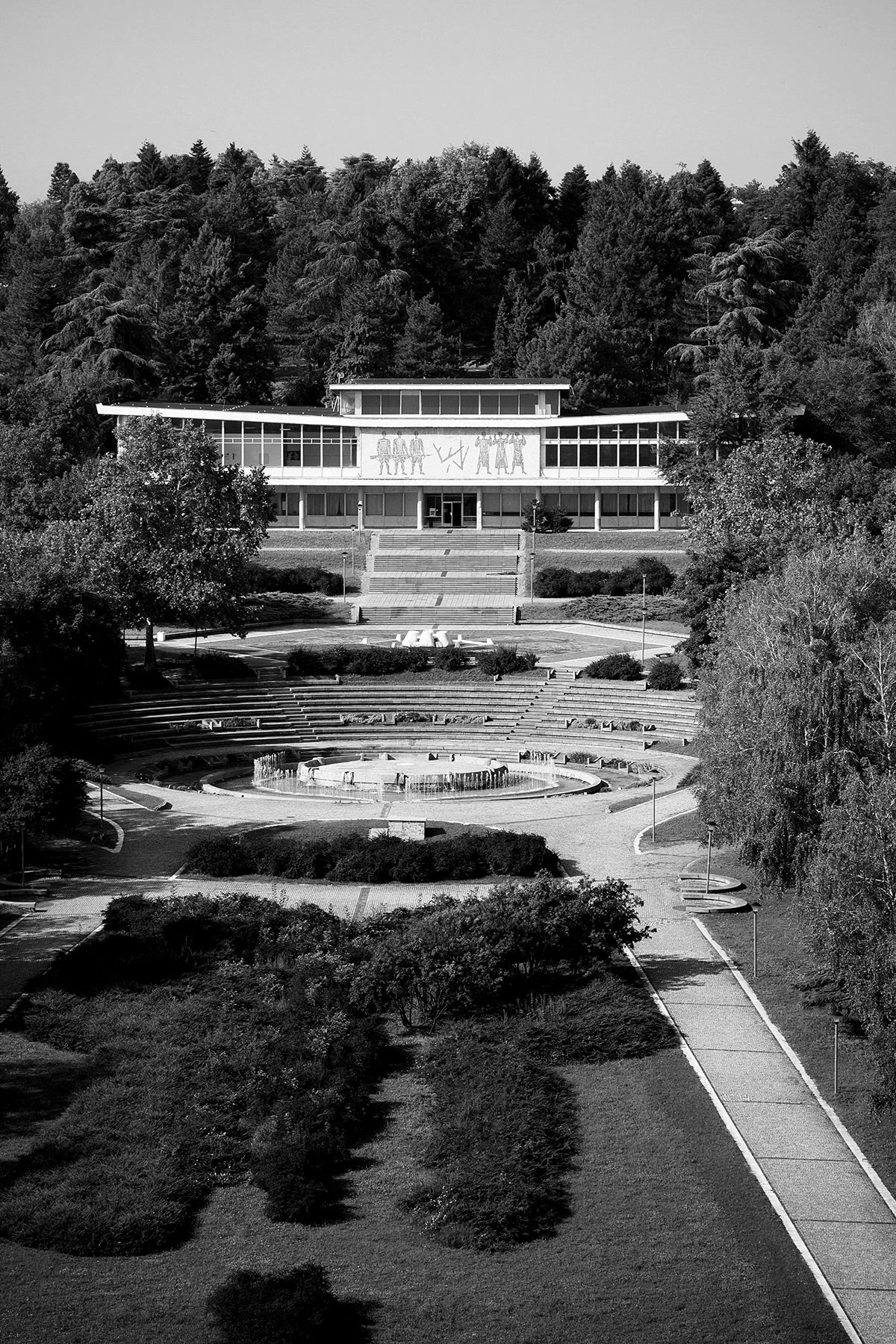

The buildings featured include the “Toblerone” apartment block, a concrete tower with sharply triangular features, the bulbous glass form of the Museum of Aviation, and the geometric Pionir Sports Hall. “By the 1960s with stability and progress, a new generation of Yugoslav architects emerged, who began to express individual creativity and to explore new borders of expression,” says Slavković. “Many young architects built their careers on opportunities and projects architects today can only dream of.”

As a style of architecture, Modernism is notoriously polarizing. “Of course, as it is always the case with something new, this architecture was also raising a lot of questions and disapproval by the public,” says Slavković. “However, many of the best buildings of Belgrade today were built in that period, and I believe that was visible from the start.”

The bilingual map, in English and Serbian, invites readers to recognize the significance of these buildings, even as many have been neglected. “As in the rest of the world, they are viewed both as masterpieces and as disasters, depending on who is looking at them” says Slavković. Yet, she says, “there is a lot more that can be done, since we have already witnessed some of them disappearing.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images featured on the map.

To see these buildings in their true concrete glory, check out Atlas Obscura’s Past Future Monuments of the Balkans, a 12-day tour of Modernist memorials in Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook