How to Digitize a 357-Year-Old Atlas That’s Nearly 6 Feet Tall

It’s not going to fit in a scanner.

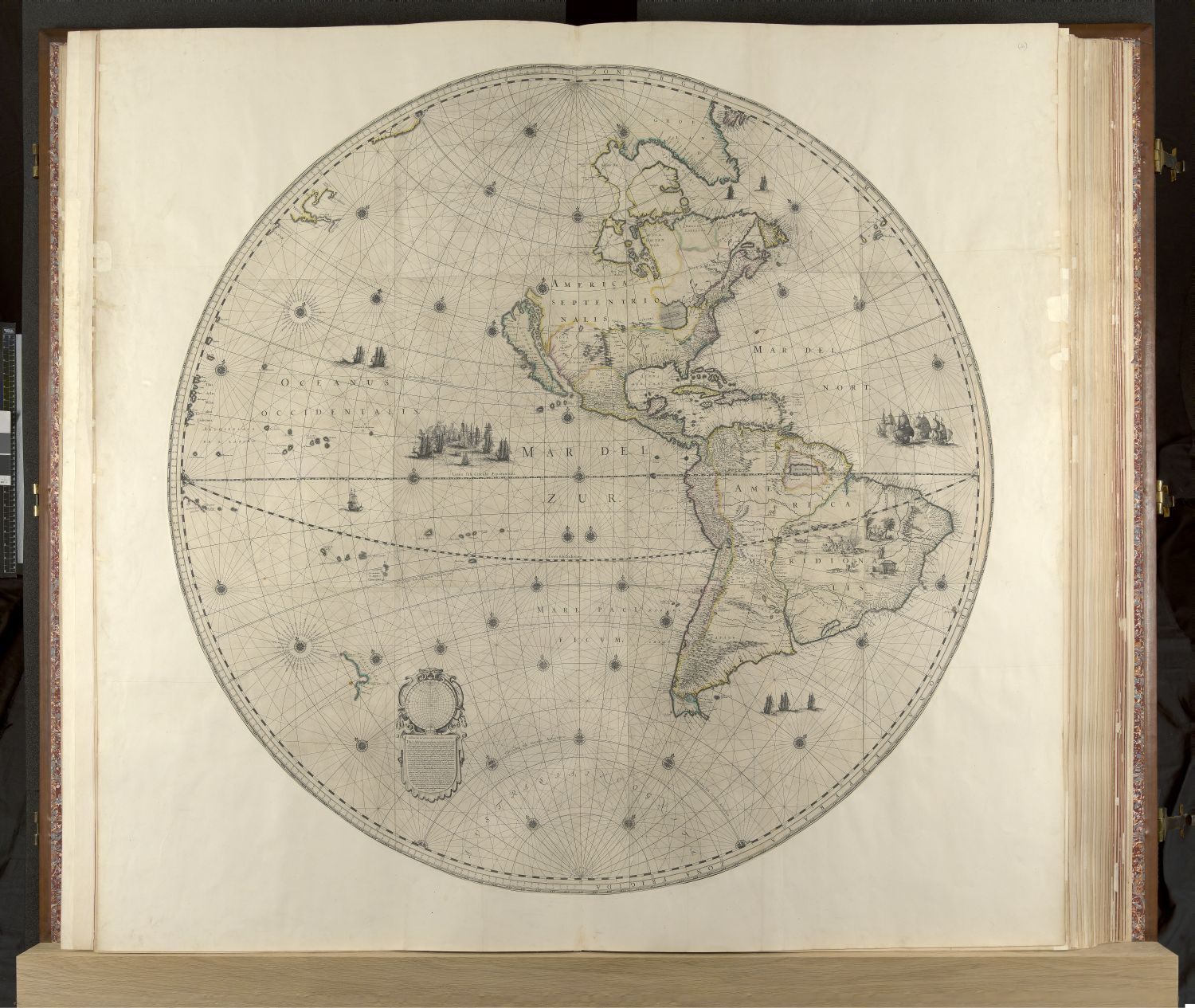

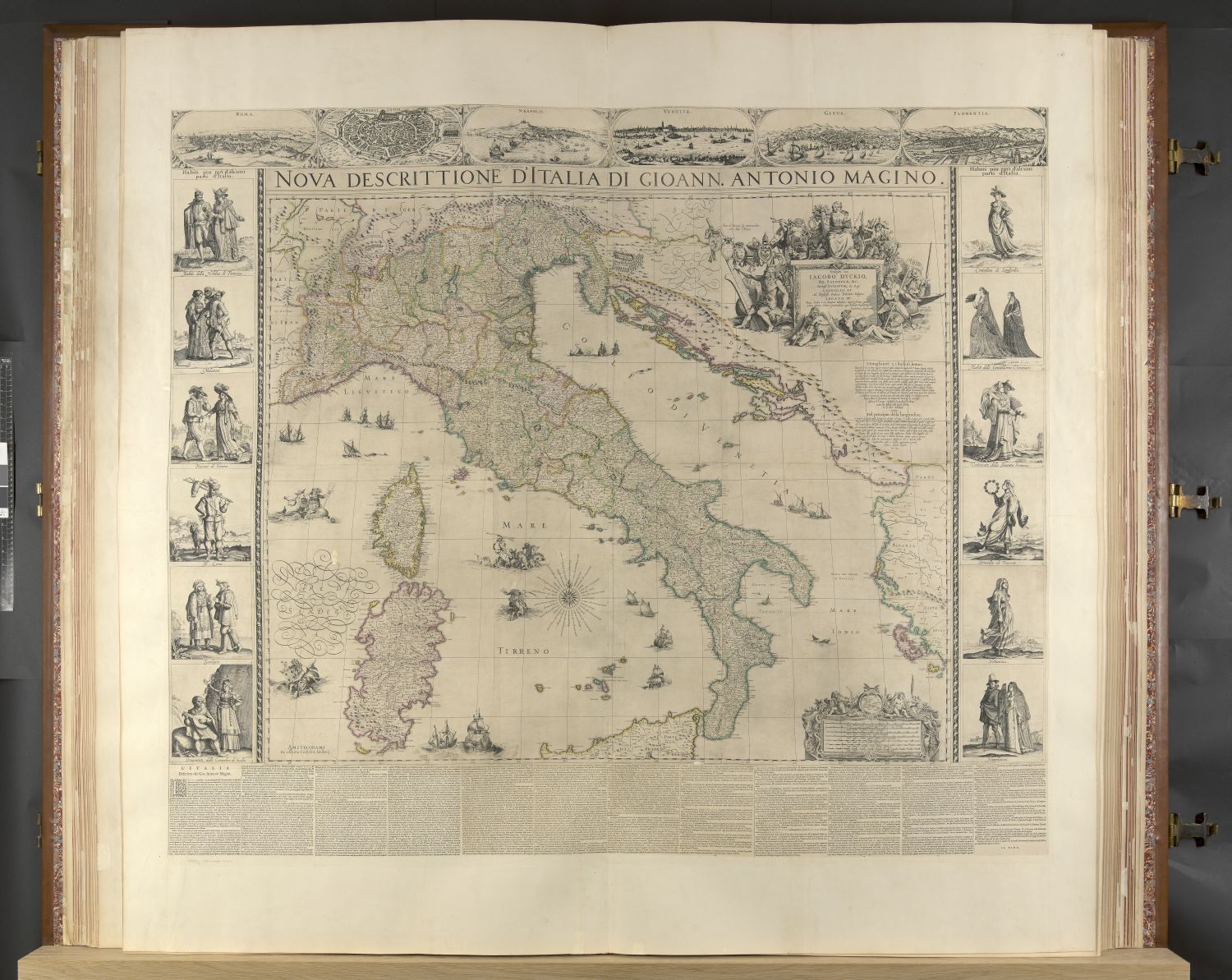

Archives and libraries are often tasked with digitizing old books in their collections to preserve them and make them more accessible to the public. Most, even very large volumes, fit in scanners created just for books, but what happens when you need to scan one that’s nearly six feet tall? If you’re the British Library, you get creative and set up a special studio to photograph the titanic Klencke Atlas. Two inclined platforms support the sides of the tome, while two people hold up reflectors to evenly illuminate the pages for a camera mounted above. The resulting photographs reveal incredible detail—and some incredible gaps in geographic knowledge in the 17th century, considering much of North America, Australia, and Antartica had yet to be charted when the atlas was completed in 1660.

The massive collection of 41 maps was made as a gift to King Charles II by Johannes Klencke, a Dutch sugar merchant who hoped to land favorable trading deals with the British Empire. Charles II was a map lover and kept the atlas in his cabinet of curiosities. And Klencke was knighted. The book stayed in the royal collections until 1828, when King George IV gifted it to the British Library with other maps and atlases.

While the maps were intended to be hung on the wall, they were left bound. This was a boon to their preservation, as they are now in better condition than those that were subjected to years of sunlight, heat, and dirt. There have been several attempts to restore the aging paper and binding over the years. The maps were trimmed and mounted on new paper sometime in the 1800s, and the volume was rebound in the early 1960s. Today the atlas is usually displayed closed, so the new photographs will allow enthusiasts and scholars to study the maps and illustrations without the trouble of cracking it open. At five feet, ten inches tall, and seven feet, seven inches wide when open, the atlas was world’s largest for 352 years, until a English publisher made one, Earth Platinum, that’s just a bit larger.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook