The Secret to This Brazilian Coffee? Ants Harvest the Beans

The insects’ trash is one farmer’s treasure.

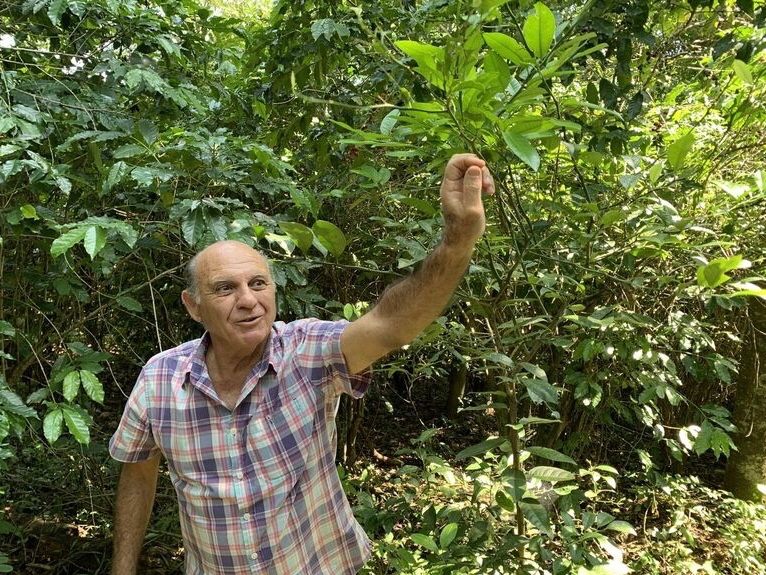

After João Neto stopped using pesticides at his coffee farm, critters that had long been absent started showing up. Birds began singing at his window in the morning, pacas paraded through the woods, and bees appeared to pollinate the flowers.

Like many producers in the interior of the state of São Paulo, one of the main coffee-growing areas in Brazil, Neto had for decades used chemicals to grow a monocrop of coffee at his Fazenda Santo Antônio farm. But his change in approach also attracted the kinds of insects that farmers often fear: beetles, crickets, and ants.

Neto, though, says he isn’t concerned about insects plaguing his crops. “Nature is in charge. If these plants have to stay here, they will resist.” According to him, all the creatures returning to his farm are important for the “natural rebalancing that the monoculture of coffees had extinguished.”

So when ants started appearing by the coffee trees, Neto did not worry or resort to killing them. But one day, on a walk around the plantation, he noticed de-pulped beans scattered around the trees.

While it’s easy to forget when ordering at a café, coffee begins its life as a fruit, and the beans are the fruit’s seed. When Neto took a closer look, he realized the ants were climbing his coffee trees, knocking down the fruits, and carrying them into their anthills. The insects, Neto concluded, must be feeding coffee pulp to ant larvae, and then discarding the beans outside the anthill.

The ants had left enough beans to fill a large coffee grinder, so Neto gathered all of the beans in a bag to study them. When he told his friend, Katsuhiko Hasegawa, a Japanese customer who has been buying his coffee since the 1990s, Hasegawa was eager to taste coffee made with the “ant beans.” What sensory notes could it have?

Ant coffee would not be the first cup of Joe whose production involves animal interaction. Some of the world’s most expensive coffee beans are partially digested and then pooped out by civets, a cat-like creature common in Indonesia, jacu birds, which are indigenous to Brazil, or by elephants in Thailand. The animals’ digestive enzymes can change the structure of the coffee beans’ proteins, which removes some of the acidity and makes a smoother cup of coffee. What Neto and Hasegawa didn’t know is whether a humble ant focused on the fruit was capable of a similar transformation.

To answer that question, Hasegawa decided to roast several kilograms of the ant beans for himself, Neto and his children, and other friends who were at Fazenda Santo Antônio that day. As he couldn’t count on a proper roaster machine—like the ones modern coffee shops boast in their entrance areas—he had to manage with a small roaster Neto bought years ago.

The group could barely contain their anxiety, and Hasegawa, says Neto, acted like he was handling a new, rare gemstone. With cups finally in hand, the ritual of moans and murmurs only heightened the expectation. “It was a coffee with different and pleasant acidity,” says Neto. “Although I am not a professional taster, I enjoyed it.”

The group widely agreed that the taste was unique. Some thought the coffee’s acidity had improved, or that the flavor resembled other floral coffees with jasmine notes. To test the commercial potential of the beans, Hasegawa took a few ounces to Japan to roast and taste with a baristas group.

Hasegawa runs a coffee shop in the hip Tokyo neighborhood of Ginza. Called Café Paulista, it was named after the Brazilian state where most of the coffee beans in Japan originally came from. The café was opened in 1911 by Ryo Mizuno, a Japanese entrepreneur who brought the first Japanese immigrants to Brazil to work on coffee plantations. Since Hasegawa inherited Café Paulista from his grandfather, who bought it from Mizuno, he’s retained the legacy of maintaining a close partnership with Brazilian farmers.

So when Neto’s Brazilian ant coffee traveled to Japan, it reflected a century-old relationship. Hasegawa says the Japanese baristas were excited to taste it, and intrigued by the story behind it. When they tried it, some believed the coffee had gained interesting acidity characteristics, while others said that the ants had given it sweeter notes. Overall, they liked it.

Although the baristas’ response was positive, Hasegawa couldn’t take any orders, because the farm’s production of the beans has been very limited. With the new organic approach, Neto’s coffee production has dwindled from more than 230 hectares to just 40 (from 570 acres to just 100). In his biggest year, 2015, Neto cataloged less than 60 pounds of these ant beans. He hopes to soon be able to sell tiny amounts to customers. But, for now, he only makes ant coffee samples, and he does not know of anyone selling ant coffee commercially.

Not only is producing the beans a “little ant job,” as is said in Brazil, a local expression meaning something that takes a lot of effort. But the relationship between insects and coffee trees can take a very long time to develop.

That’s according to Susanne Renner, a botanist from Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. She notes that the symbiosis between some ants and their Rubiaceae species (the family that includes coffee trees) evolved over about three to five million years. The Phildris nagasau, an ant discovered on the island of Fiji, even plants, fertilizes, and guards its own coffee crops.

“We believe that it started with the nesting behavior of ants who have lost the ability to live in any other nest or build their own nest,” she explains. “We don’t know why Rubiaceae, instead of, for example, other plant species.” This close relationship has been known since about 1880. “Our discovery,” Renner says, “is that the ants actively collect and then plant the seeds of their house-plants by inserting them into cracks in the bark of canopy trees.”

The studies conducted by Renner with PhD student Guillaume Chomicki, whose research called for climbing trees in Fiji for a closer look, shows that this symbiosis happens regularly. It also suggests that ant species around the world may have relationships with coffee trees—Neto’s ants being a good example.

In sharp contrast to the advice of internet posts that suggest spreading coffee grounds to deter ants, new studies suggest that household ants are attracted to coffee odor. Researchers have found that several varieties, particularly Arabica, are attractive to some foragers ants, such as Tapinoma indicum, Monomorium pharaonis, and Solenopsis geminata.

This research is shedding light on the relationship between ants and coffee trees, and similar studies could one day support the production of coffee by the tiny, hard-working creature, and investigate Hasegawa’s belief that the ants notably changed the coffee’s characteristics. In any event, João Neto will let the ants do their job.

“Who knows if eventually we will have a significant amount to sell in the market?” Neto says. “The quantity of ants is increasing on the farm.” Unlike any other coffee farmer, he seems very happy about it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook