These Simulated War-Zone Villages Train U.S. Soldiers for Deployment

Pretend streets, fake wounds, and actors playing snipers all add to the immersive experience.

On dusty backroads at American military bases, men dressed in robes sometimes emerge suddenly from between cinderblock buildings, brandishing AK-47s and rocket launchers. Protests break out at town squares, lined in walls scrawled with graffiti. Women wearing headscarves tuck baby carriers under their arms and scuttle past watchtowers to avoid sniper fire. Yellow and orange flames from explosions course through the streets.

But nobody really gets hurt, at least not yet.

These alarming scenarios are playing out at American training facilities in the U.S. and Europe, designed to resemble urban centers and villages in the war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan, and to prepare soldiers with believable immersive experiences. Sprawling for miles, they have been given fictitious place names like Braggistan, Talatha, Atropia, and Dara Lam. They are populated with mostly amateur actors, happy to have work in rather remote parts of the country. The ranks of paid players include immigrants from Iraq and Afghanistan; spouses of American soldiers; and amputees, some of them wounded veterans from wars in Korea and Vietnam.

The photographer Christopher Sims has been documenting the installations for more than a decade, for exhibitions and a book due out in two years or so, Theater of War: The Pretend Villages of Iraq and Afghanistan. Each of these sites, he says, “is like a fully fledged universe.”

Sims, who serves as the undergraduate education director for Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, has photographed training grounds at Fort Polk, Louisiana; Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Fort Irwin, California; and the Hohenfels base in Germany. Escorted by public affairs staffers, he sometimes spends days in a row roaming the pretend streets.

He has become, he says, “weirdly appreciative of the slight variations between villages.” In his desire to visit as much as the military will allow, he feels a “collector-type impulse” toward comprehensiveness of these imaginary worlds.

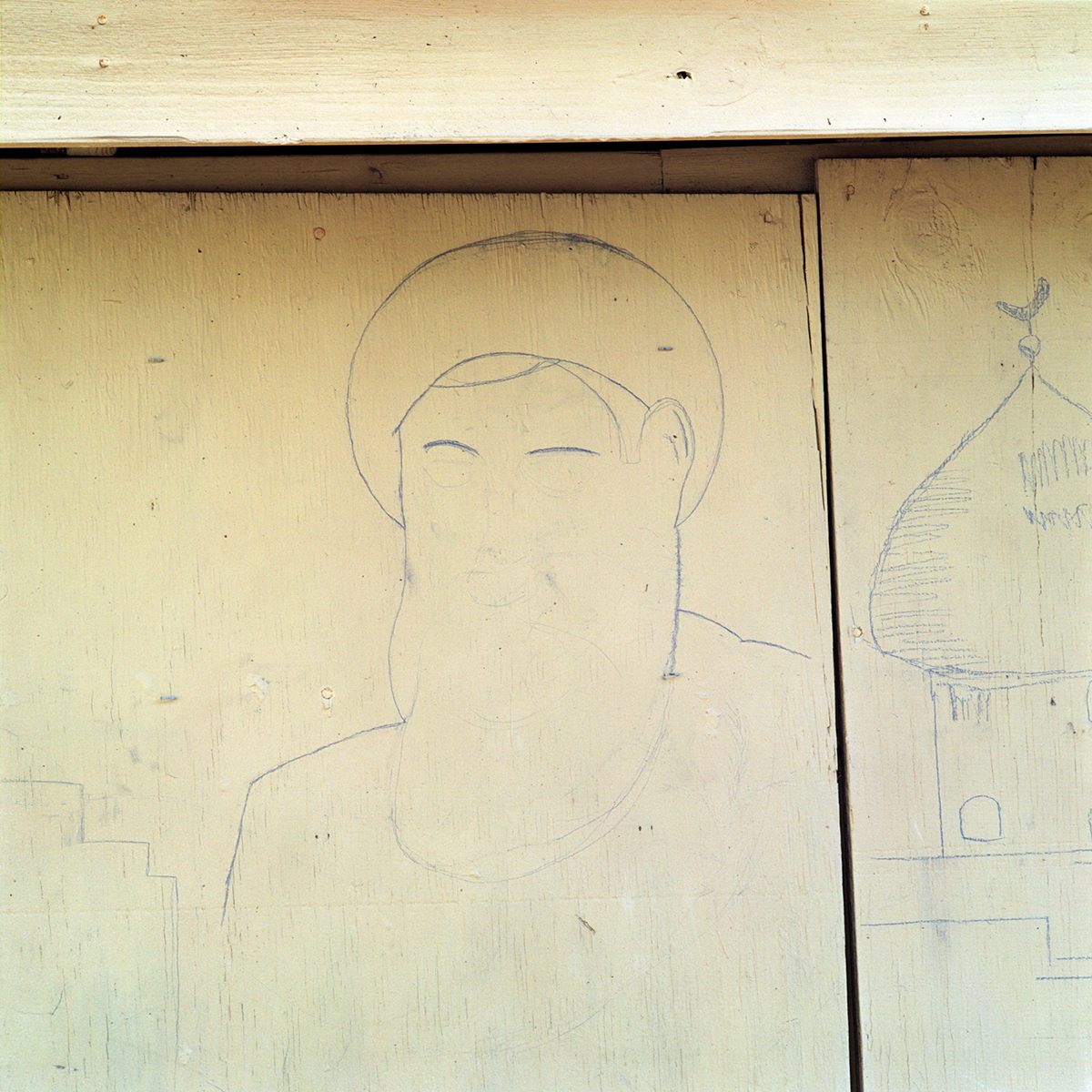

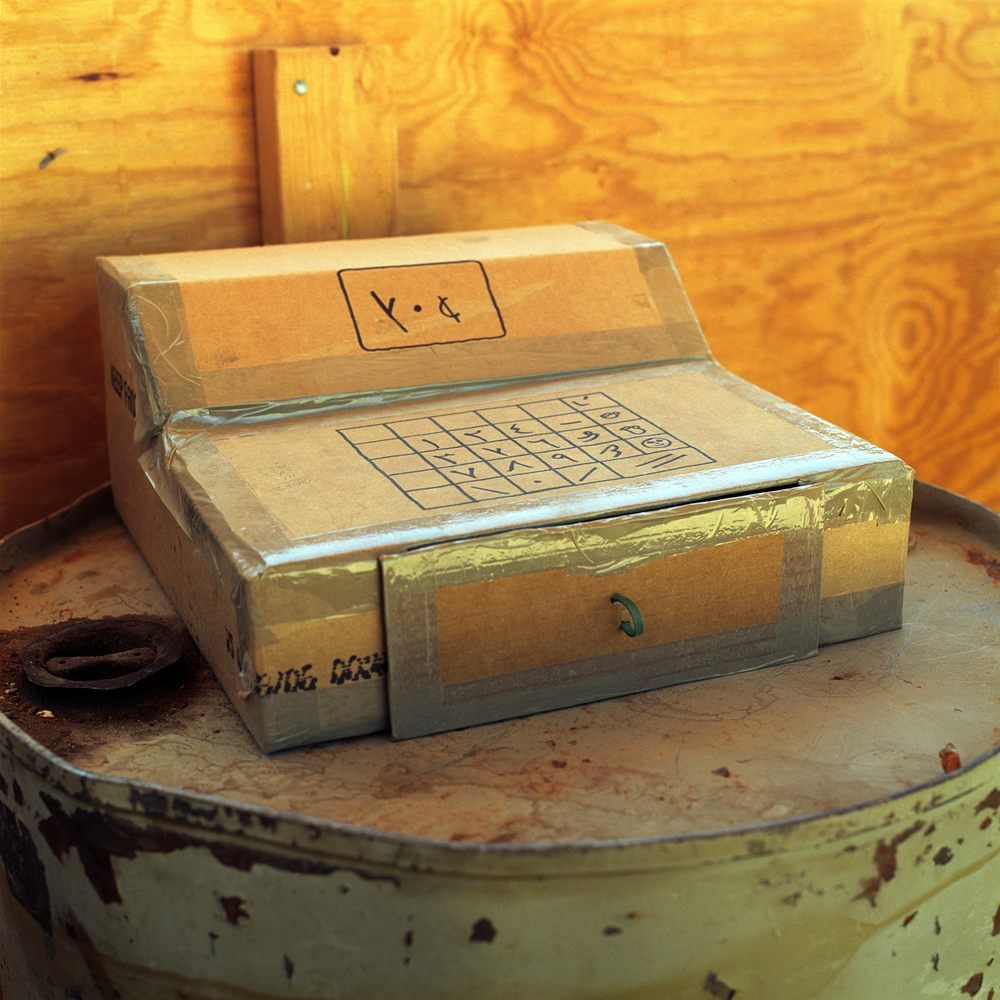

Some of the buildings look makeshift, cobbled together from shipping containers and prefabs, while others have culturally appropriate details, like foam cladding that imitates stucco. Sims has watched particular enclaves evolve during his repeat visits over the years: propaganda murals have faded, and signs in Spanish—left over from the days of practice for Latin American military threats—have given way to Arabic counterparts.

Simulated newspapers are published in the villages, and there are performances of radio and TV shows. Military personnel and civilian experts supervise the trainees as they go about their partly scripted daily encounters, practicing to invade airfields or to hold introductory meetings with wary local dignitaries. The trainees wear halters with electronic sensors, which record simulated hits from snipers’ bullets, explosions or friendly fire.

Sims has photographed the actors dressed as café owners, young mothers, doctors, politicians, aid workers and policemen. He has documented how they sometimes spend their downtime on the bases, knitting, weaving, planting and harvesting crops or painting murals. Occasionally they walk around with gruesome fake wounds, even organs spilling out. In 2006, at Fort Irwin, Sims was given his very own role to play, as a video cameraman for the fictitious International News Network.

Fort Irwin also gave him some sense of what war zones smell like. Equipment there can generate realistic aromas, whether gunpowder and scorched flesh or freshly baked bread and other “pleasant ones that could be used to entice soldiers around the corner,” Sims says.

The staff members and actors have been grateful for his interest in their work creating a realistic illusion and valuable teaching tool. “They appreciate that somebody appreciates it as much as they do,” he says. He has faced only a few restrictions on the road: some Iraqi-born actors have asked him not to show their faces, to protect their relatives back home.

He has researched the historical precedents for the installations, including Tigerland at Fort Polk, set up in the 1960s to represent Vietnam, and Krasnovia at Fort Irwin, where tanks in the 1980s were modified to look like Soviet equipment and Soviet uniforms were handed out for training exercises.

Among Sims’ previous major works was a study of Guantanamo Bay, another artificial walled-off and armed world unto itself. His images are full of ironies and jarring contrasts. A buffet table is laden with fresh fruit, although most Cubans can barely afford farm produce. Sports stadium bleachers and children’s playground equipment sit eerily unused, baking in the Cuban sun. A portrait of Martin Luther King hangs in a cafeteria where perhaps hardly anyone has much left in the way of dreams and hopes for reaching promised lands.

Within the next year or so, Sims says, he hopes to revisit the pretend villages in the U.S. and Germany. Although they can change with every generation of leadership and shift in foreign policy, he says, “the dream would be to have unlimited access and map it all to the nth degree.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook