The Long, Slightly Strange History Behind Fingernail Clipping

Everyone does it.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Fingernails have a functional purpose—they’re shells for our fingertips—but they sure come with an annoying side effect.

That effect? The fact that, every couple of weeks, you have to cut them. No matter who you are, you have to go through this process where small pieces of your keratin fly everywhere because you’re shoving them in a nail clipper. But the modern nail clipper is a fairly recent phenomenon, roughly as old as the Swiss Army Knife. Which means that for most of human history, clipping one’s nails was a little harder than digging your rusty clipper out of the medicine cabinet.

Nail-clipping history, it turns out, is also surprisingly complicated, a hygienic practice that at times was shrouded in superstition, in addition to including a lot of unknowns. Who invented the ubiquitous modern nail clipper? That’s one fact, for starters, that we might never know.

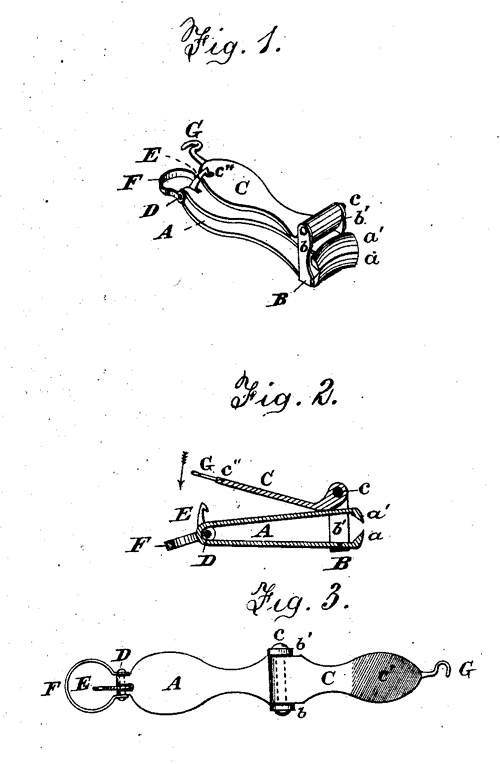

Around 1875, patents for the modern nail clipper began to appear, with the first such trimmer, designed by a man named Valentine Fogerty, though the design of his device could best be described as a circular nail file rather than a keratin clip. The first design in the USPTO’s files that I could find with anything in common with modern designs came from inventors Eugene Heim and Oelestin Matz, who were granted a patent for a clamp-style fingernail clipper in 1881. (These days, standard nail clippers are so common that any patents on them have long since faded away, though that hasn’t stopped new variations from being created, much like with the umbrella. Who hasn’t ever wanted a nail clipper that automatically stores your nail clippings?)

Both devices were trying to solve a problem that, before then, was solved with old-fashioned knives. Take the patent for R.W. Stewart’s finger-nail cutter, which has more in common with peeling an apple than pressing a clamp. And if you’ve ever used a paring knife to peel an apple, that’s how fingernails were cut before there was a designated tool for it, whether using an actual knife or small scissors. In fact, based on my research, terms like “trim” or “cut” generally weren’t used to describe the process until the 19th century. Before that, we described it as “paring.”

Still, by the end of the 19th century, superstitions about how and when to trim fingernails were pretty common. An article published in the Boston Globe in 1889 (though credited to the New York Sun), noted that one superstition of the time was that people couldn’t cut their fingernails on weekends out of fear that it might lead to back luck.

“It is unlucky to cut the finger nails on Friday, Saturday or Sunday,” the article explained. “If you cut the on Friday you are playing into the devil’s hand; on Saturday, you are inviting disappointment, and on Sunday, you will have bad luck all week. There are people who suffer all sorts of gloomy forebodings if they absentmindedly trim away a bit of nail on any of these days and who will suffer all the inconvenience of overgrown fingernails sooner than cut them after Thursday.”

(Let’s be honest: This superstition sucks. A much better superstition: The idea that white specks on the fingernails would lead to good fortune.)

But all this chatter about paring knives and superstitions only gets us back two centuries. Where do we go after that?

Well, since we don’t have a firm backing for a lot of this historic stuff, literature is a helpful friend. In 1702, for example, Irish dramatist George Farquhar’s The Twin Rivals makes a reference to nail-paring.

“… I found another very melancholy paring her Nails by Rosamond’s Pond,” according to one passage, “and a Couple I got at the Chequer Alehouse in Holboure; the two last came to Town yesterday in a Weft-Country Waggon.”

Going back further, we know a few other things about fingernails, like the fact that the longer your nails were during China’s Ming Dynasty, the less likely it was that you did hard labor. But our interest in well-groomed fingernails comes from even further back: the ancient Romans, to be specific.

Again, the evidence comes from literature. The satirist Horace repeatedly touched upon fingernails in his works. In the work Satires, dated 35 B.C., Horace came up with the idiom of biting one’s fingernails out of nervousness (or as he put it, with some modernization, “… in the composition of verses, would often have scratched his head, and bit his nails to the quick.”)

But a later work, the first book of Epistles (circa 20 BC), offers up the largest historic hint. In a passage where he introduces an auctioneer, he also makes reference to the process of nail trimming in ancient barber shops. A modern reference from Poetry in Translation:

Philippus the famous lawyer, one both resolute

And energetic, was heading home from work, at two,

And complaining, at his age, about the Carinae

Being so far from the Forum, when he noticed,

A close-shaven man, it’s said, in an empty barber’s

Booth, penknife in hand, quietly cleaning his nails.

Also in Horace’s time was a pivotal moment in the history of nail polish. Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra, who lived between 69 and 30 B.C., was known for using the juice of henna plants to paint her nails in a rust-red color—and due to the social code of the time, she was one of the few to dye her nails red.

Going even further back, there’s a reference to trimming fingernails in the Old Testament, Deuteronomy 21:12, replete with some ancient gender politics. Per the New American Standard translation:

When you go out to battle against your enemies, and the LORD your God delivers them into your hands and you take them away captive, and see among the captives a beautiful woman, and have a desire for her and would take her as a wife for yourself, then you shall bring her home to your house, and she shall shave her head and trim her nails.

So, a written acknowledgement of fingernail-trimming that dates back to, roughly, the eighth century B.C.—long before Valentine Fogerty’s existence.

But let’s say, after reading all that, you’re more interested in where nail-clipping is going, rather than where it’s been.

To put it simply, the clipper has evolved in some weird ways in recent years, including:

Giant handles: Do your toenail clippers need a strong grip so they don’t keep falling out of your hands? If so, the well-reviewed Bezox Precision Toenail Clippers might be your ticket. Maybe they’re overkill, but so are your toenails.

A rotary turn: One of the problems with standard-size fingernail clippers is that one hand is often stronger than the other, meaning that when your non-dominant hand cuts, it’s more likely to slip, making it more likely to bend a nail. A potential solution the the problem comes in the form of a rotary nail clipper, which turns the clamping motion on its side.

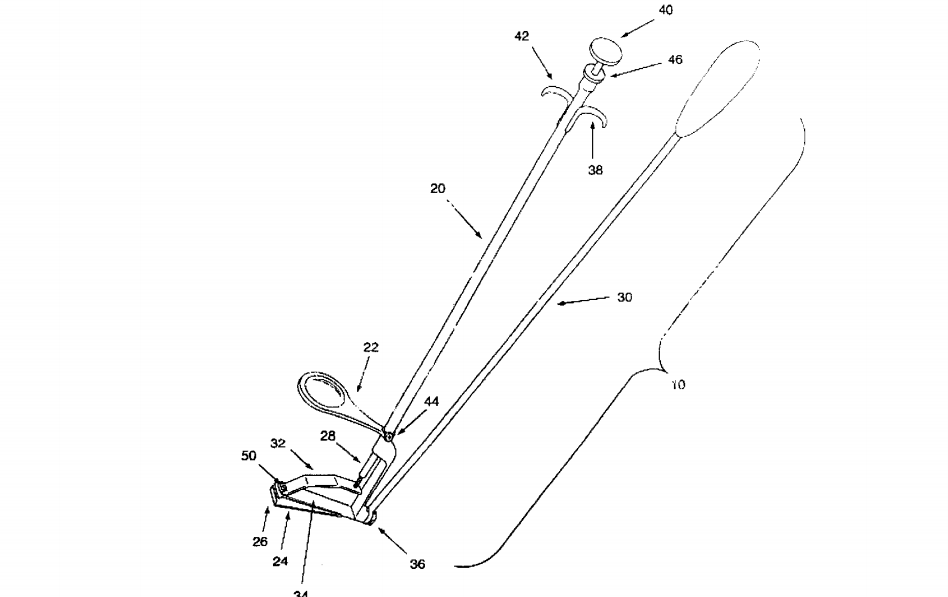

Really long clippers: Combining the first two items in a wacky way is the Antioch Clipper, a device introduced in 2011 to make it possible to clip toenails without bending over at the waist—which may be of benefit in some cases, but lends itself to a design that is best described as a combination nail clipper and pair of tongs.

Really expensive clippers: Do you really need the world’s best nail clipper at your disposal, as the Khlip Ultimate Clipper describes itself? Perhaps not, even though it “gives you increased control and leverage as you trim your nails” due to its award-winning design. A Gizmodo review really says it all: “The Klhip Ultimate Nail Clipper Is Ultimately Just Expensive.”

Going electric: The Vanrro V1, a futuristic nail clipper, is looking for support on a crowdfunding site, though the term clipper is actually a misnomer—it’s really a nail grinder, kind of like the sort they sell for dogs. But the attempt has only raised $210 so far, and a similar effort shut down with no notice whatsoever last month. Hey, at least the clippers don’t support IFTTT.

But maybe the real issue isn’t the clippers—but that you don’t know how to clip your nails the right way, to ensure they’re even all the way around. Fortunately, there’s plenty of advice on that.

“Look at all ten nails and pick out the shortest, or that with the smallest amount of ‘white’ at the tip,” notes Deborah Lippmann a celebrity manicurist, in an article at GQ. “Use that nail as a reference to ensure all nails are being filed to a uniform length and shape.”

Lippmann also recommends using an actual emory board on your nail, treating your cuticles right so as to avoid hangnails, and to leave a sliver of “white” at the top of the nail.

The best-looking fingernails, in other words, aren’t cut with anything special, they are just the ones with the most TLC.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook