Will ‘Flameless Cremation’ Catch On?

Bio-cremation techniques make burning the dead look old-fashioned. So what’s stopping people from choosing it?

From flaming Viking funeral boats to the efficient infernos of modern crematoriums, humans have a long history of using fire to dispose of our dead. But traditional cremation practices can produce a number of toxic emissions, including high levels of mercury. Today, some funeral homes are embracing an alternative from the exact opposite end of the elemental spectrum, by using water to “cremate” the deceased. Trigger warning: things are about to get clinical.

Technically called “alkaline hydrolysis,” the process of using nothing more than water, heat, and a small amount of chemicals to break down a body is also known as “bio-cremation,” “resomation,” or simply, “flameless cremation.”

“It was our firm that coined the term ‘flameless cremation,’” says John McQueen, president of Anderson/McQueen Funeral Homes in Florida. Anderson/McQueen was one of the first businesses in the world to provide the service commercially, in 2011, and they are still one of only a handful of outfits in the world that offer flameless cremation to the general public.

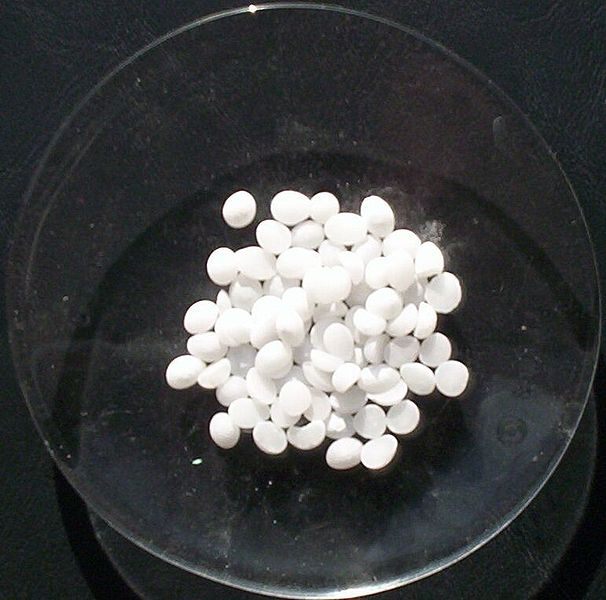

The process is relatively simple. A body is placed into a machine much the same way it would be placed into a traditional cremation oven. Once the chamber is sealed, it is filled with a mixture of 95 percent water and 5 percent lye (potassium hydroxide) and heated up to over 300 degrees. After a few hours, the chemicals and heat have done their work dissolving the soft tissue, and all that’s left are bones and a brown chemical liquid. “It looks like iced tea basically,” says McQueen. As an odd side effect, the process also preserves and cleans artificial implants such as pacemakers or hip replacements.

The now-brittle bones are then pulverized, just like they would be after a fire cremation, and given to loved ones as ashes. The effluent liquid is then added to the local wastewater supply like any other sewage.

Due to the extreme heat used during the process, the effluent is completely sterilized, and the chemicals break down the soft tissue to well below the level of DNA or RNA. McQueen stresses that there are no identifiably human components left in the effluent. “The city of St. Pete has said it’s probably the cleanest thing to go down our sewer system. Because of the lipids in the body, it acts sort of like a soap,” he says.

Depending on the type of machine being used, the process can take anywhere from three to 12 hours. McQueen’s machine, a high-end computerized model that weighs the body and automatically calculates the necessary fluid levels to use, can dissolve a body in three to four hours.

Flameless cremation produces no fumes or smoke, and requires much less energy, space (“Technically you could put one of these units on the tenth floor of an office building,” says McQueen), and maintenance than traditional flame cremation. So why hasn’t this cleaner, gentler, more efficient method caught on? Well, it’s complicated.

“The funeral industry is a very slow industry to change. It’s based in tradition,” says Ryan Cattoni of the bio-cremation firm AquaGreen Dispositions. Both Cattoni and McQueen say that the funeral industry, which is largely governed by the closely held death customs of the cultures in which they operate, is often resistant to new ways of doing things. It can be hard to convince people to try something else. “In all honesty there are a lot of funeral directors out there that don’t like the idea of the bio-cremation,” says McQueen. “There’s a lot of funeral directors out there that don’t actually think it should be called cremation.”

Another major obstacle facing the adoption of flameless cremation is that it isn’t technically legal in a lot of states. “Every state has cremation and funeral directing rules and regulations that classify methods of disposition,” says Cattoni. “Some states don’t have the wording in their regulations to allow it.” Cattoni himself had to lobby to change the laws in Illinois, where his company is based, just so they could operate. Even in Europe, where the process was originally developed, it is almost universally illegal. McQueen estimates there are about 15 states in the U.S. where flameless cremation is currently legal.

Then there is the cost. McQueen says he spent $450,000 on his flameless cremation system, as opposed to the cost of a traditional flame crematorium, which he says is only around $150,000. Consequently, the flameless cremation option is more expensive than a traditional disposition, but not by much. For instance at the Anderson/McQueen facilities, the difference to the customer, no matter how extensive the overall funeral and cremation package, is just $145.

Obstacles aside, a growing number of families are opting for the process when it is available. McQueen says that about half of his clients choose flameless cremation for its ecological benefits, while the other half choose it because they just don’t like the idea of a loved one being burned. Cattoni has seen a similar trend. “I’ve found the people who like the process are the people who like the idea of no fire or burning,” he says. “Whether it be for religious reasons, or it’s just in our DNA that when we see fire, we see danger.” McQueen says that one his former clients has been quoted as saying that flame cremation reminded her of the Holocaust.

As environmental regulations make it more and more difficult and expensive to operate flame crematories, flameless cremation may one day become the industry standard. But considering how slow the funeral industry is to evolve, and the difficulty some have in getting over the “yuck factor” of a body dissolving, it’ll probably be a while. “It won’t be in my lifetime,” says McQueen. “It might be when my son’s sitting in this chair.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook