The Lost Constellation Meant to Honor a King’s Escape

The oak tree that sheltered Charles II once had a place in the night sky.

In 1651, after the Battle of Worcester, Charles II—who would go on become the king of England—climbed a tree. The future monarch would later claim to have ensconced himself in the branches of an oak in Boscobel Wood while his enemies (troops who fought the Royalists over how England should be governed) passed just below. Legend has it that “he had to stay there, dead quiet, until they buggered off,” says Matthew Edney, a geographer at the University of Southern Maine.

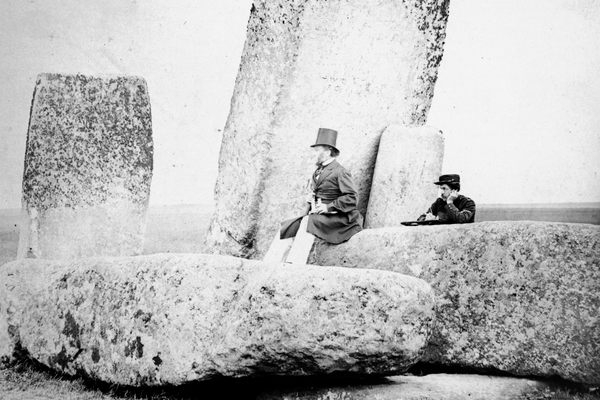

The hiding spot, dubbed the Royal Oak, was commemorated on pieces of pottery and, once the monarchy was restored, with a holiday. It was also—for a little while, at least—mapped onto the cosmos.

In 1676, years before he observed the comet that would carry his name, a young astronomer named Edmond Halley set up an observatory on the volcanic island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. From this far-flung speck of land, he intended to catalog the stars of the Southern Hemisphere. Halley returned to England with a slew of observations, in which he eventually included a new constellation, Robur Carolinum, or “Charles’s Oak.” The once-arborially-besieged king had become a patron, and had made Halley’s journey possible.

It wasn’t uncommon for astronomers and cartographers to transplant earthly concerns—political allegiances, debts, cultural values—into their maps of the heavens, Edney says. In national mythology, the oak tree had become a protective symbol for the monarchy. “This is a way for Halley to curry favor with Charles II,” Edney says. Halley said as much himself. When he presented his findings to the Royal Society, he included a note that read, “In memory of the hiding place that saved Charles II of Great Britain etc., deservedly translated to the heavens forever.”

In addition to maintaining the king’s good graces, Halley’s constellation was also a relatively straightforward way to resolve (or at least obscure) an issue that had long confounded astronomers with a penchant for constellations: the fact that the stars don’t always organize themselves into an imagined image.

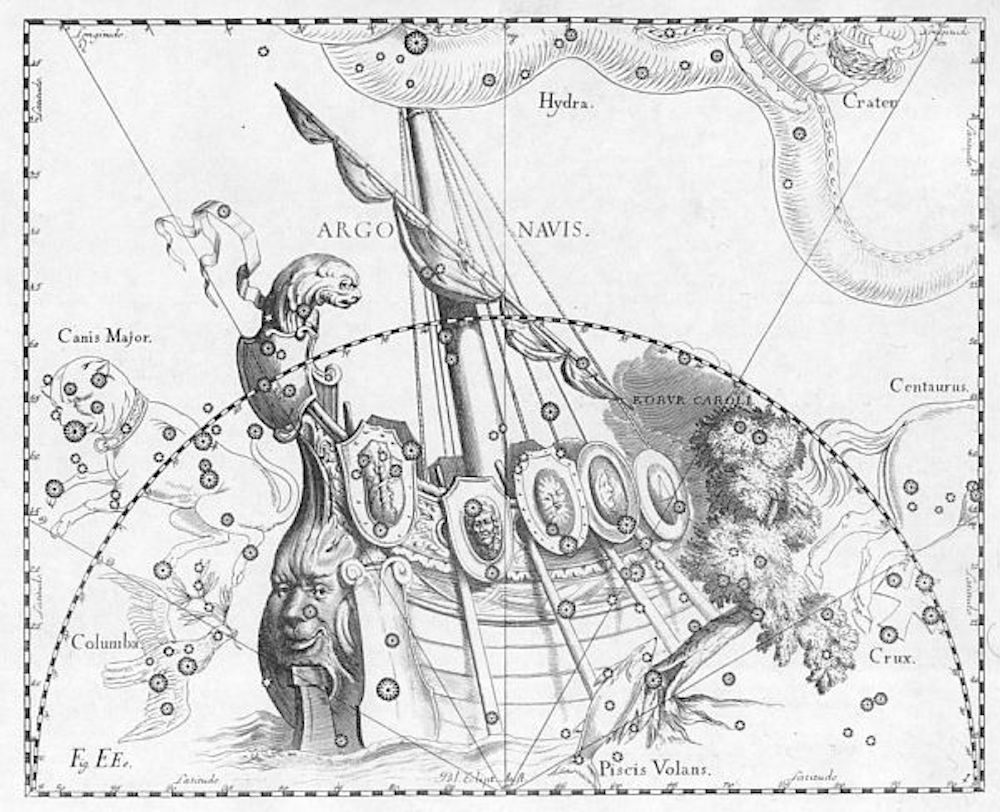

Take Argo Navis, named for the mythological ship that Jason and his compatriots took in search of the Golden Fleece. “Nature did not exactly oblige in giving astronomers a complete set of stars with which to define the ship,” writes the astronomer and author John C. Barentine in The Lost Constellations: A History of Obsolete, Extinct, or Forgotten Star Lore. A handful of stars could credibly form the hull, mast, and other parts, but nothing quite resolved into the prow. To compensate, Barentine continues, “those seeking a figural depiction of Argo were left to come up with ad hoc ways to hide the fact that part of the boat was literally missing.” Cartographers sketching the constellations disguised its absence with a strategically placed atmospheric flourishes—a cloud or a boulder. Halley’s plopped a tree in its place, obviating the need to actually complete Argo Navis.

The French were not on board. As Barentine notes, “there was probably some patriotic chauvinism involved, since to include the oak would have honored the king of a foreign country that still claimed ceremonial sovereignty over France.” In any case, the tree wasn’t rooted for long. Describing constellations in the 1750s, the preeminent French astronomer Nicolas-Louis De La Caille rapped Halley’s knuckles over “detaching” some stars from Argo Navis; it wasn’t proper to have the stars belong to both. De Caille added that he “cannot approve of the fashion in which Mr. Halley took them to make up his constellation.”

Back on Earth, an oak still stands on Boscobel’s grounds, and is often described as a descendant of the one where Charles II hid. And another answer was found to the Argo Navis conundrum—it was broken up into a handful of smaller, perhaps more coherent constellations, but the tree did not find its way back in.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook