Forgotten Heritage: Wind Tunnels of the Jet Age

The side view of a propeller rig at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

The side view of a propeller rig at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

For decades, the town of Farnborough, located around 40 miles southwest of London, was the United Kingdom’s prime testing and development hub for propeller-driven planes, jet engines, and gas turbines. Two test sites, the National Gas Turbine Establishment (NGTE), and its precursor, the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) of Farnborough, made use of dramatic wind tunnels and massive fans to trial the latest prototypes in aviation.

Their facilities are no longer in use, but these hulking pioneers of the jet age still remain visually stunning. Matt Emmett of Forgotten Heritage Photography has visited the sites several times to capture their staggering scale.

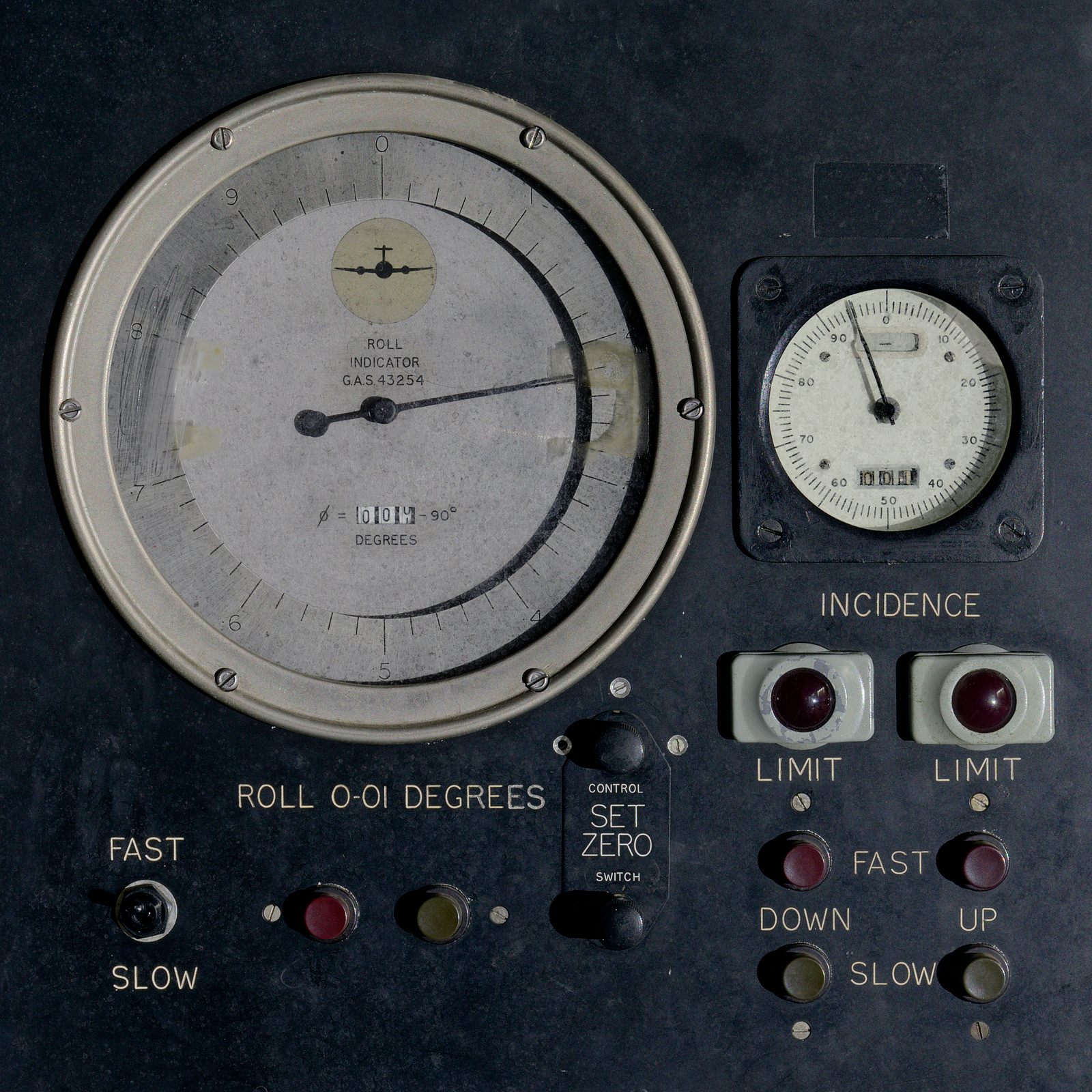

Control desk in the naval engine testing area at the National Gas Turbine Establishment (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

Atlas Obscura: Can you give us a brief history of the NGTE?

Matt Emmett: In 1940, Frank Whittle and his company Power Jets developed the first British-made jet engine to power a plane in flight, the Gloster Meteor. Over the next six years, after much success developing the technology further, the company was nationalized due to heavy government investment and merged with the gas turbine wing of the nearby Royal Aircraft Establishment. A location was secured for this new company in Fleet and the NGTE was born.

Over the next 50 years, the NGTE designed and tested the prototypes for most of the UK’s military jet engines and naval gas turbine engines.

What was its purpose, and why is it now in disrepair?

By the time World War II had ended, the threat of the Luftwaffe had passed, but in its place was a new threat: Russia. The Cold War had begun. The NGTE, or Pyestock, as it was also known, had became a focal point in the efforts to counter this new threat. We needed new planes with new capabilities, able to out-perform whatever it was the Russians were developing. This secret arms race was essentially the driving force in pushing British science and engineering know-how forward at an incredible pace.

During its life-span, the establishment was the leading site of its kind in the world. Between its conception and the turn of the next millennium, Pyestock was responsible for the design, testing and development of virtually all of the UK’s military fighter jet engines and navel gas turbine engines. Five altitude test cells were built on site to provide a testing environment for sub-sonic and super-sonic flight. These closed loop systems used compressed air generated in a vast turbine hall known as the Air House. From this building, a mass of high-pressure blue pipes snaked outwards and across the town-sized site. The fast-moving air within could be channelled together to create even higher pressures and forced at incredible speed into any one of these four test cells.

The Cell 4. It was was built to fly Concorde’s Olympus jet engine at Mach 2 and a lowered air pressure to simulate 57,000 feet. When tests were run, it was synced with the national grid—but only at night, when electrical demands were lower. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

The Concorde project even had its own test cell on site, Cell 4. An extra power plant was built to accommodate this beast and marvel of engineering, which was capable of flying the planes’ Olympus 593 engines at Mach 2 and at a simulated cruising altitude of 57,000 feet. Even with the Air House and the extra on-site power generation, Cell 4 engine tests could only be carried out at night due to the demand it placed on the national grid. People living nearby experienced the effects of the tests as house lights dimmed and a low rumbling roar could be heard from up to several miles away.

As time progressed, new technologies such as computer simulations advanced to the point they were able to accurately predict some of the data that physical testing had been providing. With the huge cost of running the site becoming hard to justify, it was gradually closed down in stages, with the last staff leaving the site in 2000.

During 2013 the site was demolished to make way for a vast retail distribution depot, which still hasn’t been started. All the history and world-leading technology was simply bulldozed into the ground with nothing saved for future generations.

The vast 24’ diameter fan prop blades at the Farnborough wind tunnel. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

Why did you want to photograph the NGTE?

I initially went to the site to help a friend learn the basics of photography. He’d just bought his first DSLR and had suggested we do the first lesson on location. He had picked out this location after seeing pictures online and told me we would have to avoid the security patrols at the site. It made me nervous, but we went ahead and climbed over the fences in February of 2012.

That first trip changed me totally and I was instantly hooked. This site began my obsession with photographing abandoned locations, and indeed my particular fascination with industrial remnants.

The Cell 1 jet engine test area at the now demolished Pyestock NGTE. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

What’s the scale of the NGTE facility?

The site was the size of a small town, around 1.5km (0.9 miles) north to south and 1km (0.6 miles) east to west. It featured around 11 very large buildings and a multitude of smaller service buildings. Each building had a purpose that often provided a service needed by another of the buildings. In effect, the site worked like a single entity or huge machine. It was incredibly complex and expensive to run but it worked wonderfully well. At its height it employed 1600 staff.

What kind of equipment still exists at the NGTE?

During my 11 trips in 2012, I tried my best to see the entire site and almost managed it. There were power stations, turbine halls, offices, workshops, laboratories, cooling towers, treatment plants and the five pressure sealed altitude test cells where the actual engines were put through thier paces at the correct atmospheric pressures and at the correct speeds. The fastest cell (4) could ‘fly’ the Olympus engines of Concorde at Mach 2 and at a simulated (low-pressure) altitude of 57,000 feet.

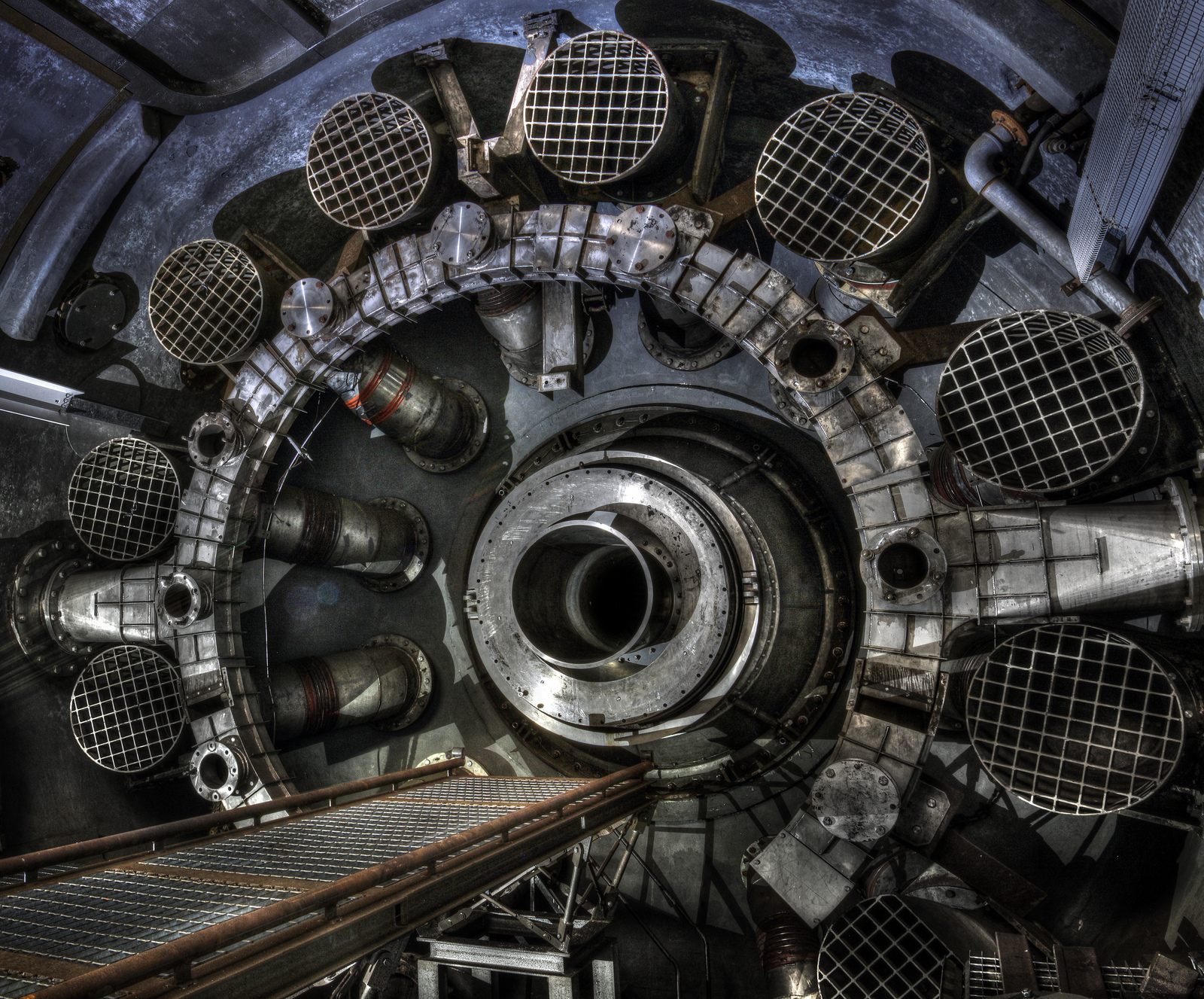

The interior of the Cell 4 plenum chamber, air was pumped into this vast space to build pressure before being forced through a narrow aperture and into the engine testing capsule. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

How does it feel to be in a place that was once so essential, and is now redundant?

Very exciting and quite sobering too. Such important work was carried out there and it changed the course of the future, in that it paved the way for the commercial passenger planes we take for granted so much now. It also made me sad that such a wonderful place with so much history could be simply destroyed.

Could you give us a bit of background on the RAE in Farnborough?

The Royal Aircraft Establishment predates the NGTE and was the precursor site, with early testing very much focused on propellor-driven planes. The site had been working on the aerodynamic properties of wings, propellors and airframes since 1917. Many of the names associated with the development of aviation are closely linked with the RAE. There are three surviving wind tunnels on site out of the five that used to exist. The largest is the Q121 24’ low-speed tunnel, where testing of entire airframes could take place. The R52 transonic tunnel and the smallest and fastest tunnel located in the R133 building. The tunnels have been largely locked down since the site stopped aerodynamic testing and are not open to the public.

The control room and observation deck at the R52 wind tunnel at the Farnborough RAE site. The viewing ports into the working section of wind tunnel can just be made out on the left. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

When and how many times did you visit the wind tunnels – and how did you get access?

I had been trying hard to gain access to the RAE for a photo shoot for around a year and a half. After extensively shooting the NGTE, getting access to shoot here felt like completing the set. After many emails, the site owners agreed to allow me in for two shoots, once to shoot at the Q121 tunnel and a second trip to shoot the R52 tunnel.

A panel in the R52 wind tunnel control room. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

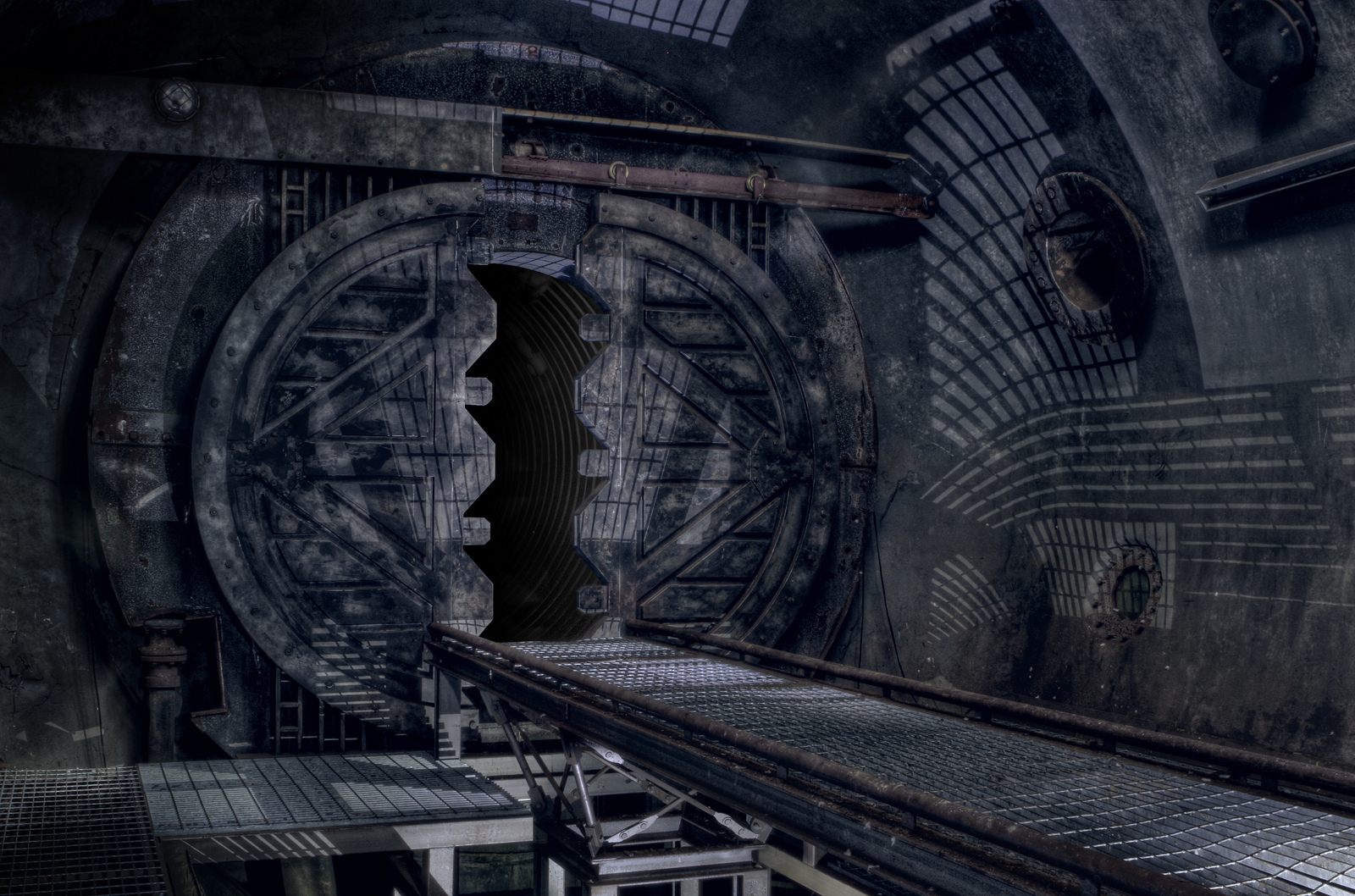

The Cell 3 blast nozzle. It was capable of producing winds in excess of Mach 1 and is also located inside a sealable chamber where pressure could be lowered to simulate high altitude. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

The Cell 3 blast nozzle. It was capable of producing winds in excess of Mach 1 and is also located inside a sealable chamber where pressure could be lowered to simulate high altitude. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

The turbine hall at Pyestock. Rows of turbines helped to generate a large amount of the suction needed to create supersonic airflow within the various testing cells nearby. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

Cell 3. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

Dial control switch within the turbine hall at Pyestock NGTE. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

Looking into what was the world’s most powerful jet engine test cell. It was built to test the jet engines of Concorde at a wind speed of over 2000mph and at an atmospheric pressure of 60,000 feet. (Photo: Forgotten Heritage Photography)

Find more of Matt’s photos of abandoned sites at the Forgotten Heritage Facebook page, Twitter account, and on forgottenheritage.co.uk.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook