France’s Legendary Haunted Lighthouse Has First Resident Since 1910

Tévennec Island and Lighthouse, located in the Raz de Sein (Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Calcineur).

For French sailors, hell can be found off the coast of Brittany.

Between the French mainland and the Île de Sein is a stretch of water known as the Raz de Sein, infamous for its violent currents. The lighthouses dotting the uninhabited islands along the waterway are difficult to reach and can house at most two lighthouse keepers living in austere conditions—earning the lighthouses the nickname “hell” from sailors and lighthouse keepers. Hell has been empty since the lighthouses were automated, but yesterday one man began a two-month residence in one of hell’s most haunted towers.

Tévennec has a special reputation among the lighthouses of Brittany as the location of hauntings and madness. In Breton mythology, death is personified by Ankou, who protects graveyards and gathers the souls of the deceased. Allegedly, boats sailing the Raz de Sein without an engine are carried by the current directly to Tévennec, leading locals to claim it is the home of Ankou and a gathering place for the souls of dead sailors.

When the lighthouse was first established in 1875, the French government classified it as a lighthouse requiring a single keeper, and like any good spooky story, eerie happenings began immediately. According to legend, the first lighthouse keeper, Henri Guezennec, was driven insane by ghostly voices demanding he leave. After the same fate befell Guezennec’s replacement, the government reclassified Tévennec as a two-man lighthouse, but the additional keeper doesn’t appear to have ended the strange happenings. According to Le Télégramme, crucifixes were embedded into rocks on the island in an 1893 attempt to exorcise it, and in 1897 the French government began recruiting married couples to keep the lighthouse, in the hopes that companionship would ease the loneliness experienced on the isolated isle. Louis and Marie-Jacquette Quéméré lived on the island with their three children, a cow, and no documented encounters with ghosts. The lighthouse was automated in 1910, and Tévennec remained uninhabited until yesterday, when Marc Pointud set out on his ambitious plan to inhabit the island for 60 days.

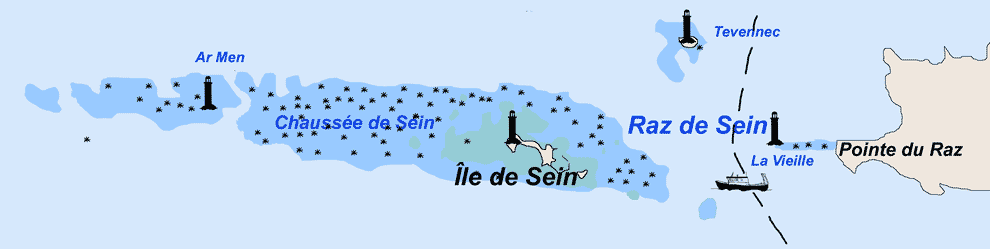

A map of the Chaussée de Sein and Raz de Sein, where lighthouses like Tévennec are nicknamed “hell” (Illustration: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain).

Marc Pointud is the president of the National Society for Heritage, Lighthouses, and Beacons (Société Nationale Pour le Patrimoine des Phares et Balises, SNPB for short), an organization founded in 2002 to advocate for the preservation and restoration of France’s lighthouses. Last year, Pointud announced his intention to occupy Tévennec for two months in a bid to raise funds for the SNPB’s efforts towards renovating the lighthouse and converting it to an artist’s retreat.

The project received some media attention in France when it was crowdfunded last summer, with VICE France interviewing Pointud about his plans. Yesterday, French newspaper Le Télégramme reported on Pointud’s departure for Tévennec and the beginning of his residency. The article highlights the difficulty of the project—Pointud and his supplies reach the lighthouse by helicopter in an operation described as “delicate,” noting that the helicopter’s pilot, Pierre de Brissac, is “not impressed” by the landing options.

Despite the logistical difficulties, there’s a clear enthusiasm for Pointud’s project among those with a connection to Tévennec; attendees yesterday included Michel Plouhinec, a lighthouse keeper whose great-grandfather was stationed at Tévennec for 15 years, along with the grandchildren of the Quémérés. Pointud explained to The Connexion that restoring the lighthouse will cost over 200,000 euros due to the difficulty in transporting materials to the island, spurring the need for publicity to attract sponsors.

But he is also embarking on this project to honor the memory of the lighthouse keepers, who spent years of their lives in hardship—with or without ghosts—to operate Tévennec: “I am proud to enroll in the tradition of the great guards who once dared, in much more difficult circumstances than me, to face the sea in places like this.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook