From Metal Coins to Venmo: A History of America’s Credit Cards

A charge account plate for Goldwater’s Department Store. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A charge account plate for Goldwater’s Department Store. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The credit card as we know it is more popular than ever. It’s also dying.

According to a 2013 Federal Reserve study, the number of credit card payments in the United States passed the number of check-based payments for the first time a few years back, and debit cards passed that mark way back in 2004.

Sadly for some, the magnetic swipe isn’t long for this world—the industry is switching to a chip-based system this year, and mobile payments threaten to put cards out to pasture soon after that. It’s not hard to imagine a world where your phone is your bank account and your credit card; think how easy it use to use Venmo or PayPal. Or, looking even farther, where biometrics or virtual reality come into the financial as well as the identity and entertainment spheres.

But you probably know a lot about credit cards today. What you don’t know is where they came from and why they became so popular. That story starts at the old general store.

During the 1800s, American general stores kept track of credit by writing customer names into a ledger. If a person didn’t pay up, a debt collector would likely show up at the person’s house. Unlike nowadays, when debt collectors flood your mailbox and won’t stop calling you, these debt collectors usually drove up to your home in a horse cart, with the words “debt collector” written on the side, and take your stuff back. Not exactly subtle—and if you’re being targeted by said debt collector, pretty embarrassing.

But credit was nonetheless useful back then. Loose change was a pain to carry around, especially for large purchases. Just like nowadays, it’s dangerous to walk around with a lot of money in your pockets ahead of a big purchase.

Eventually, credit cards came about as a way to solve the issue. The original credit cards came from department stores in the early 20th century, handing out metal coins or charge plates to track a user’s spending against their credit at the store. The coins were imprinted using ink to track the amount spent on a sheet of paper, along with the person’s address.

Metal charge plates, which either looked like dog tags or tokens, had a bit of status-symbol appeal. Often given leather cases, the devices have a nice vintage look, which means you can find them on eBay or Etsy, often selling for the low tens of dollars.

The Charga-plate. (Photo: Marilyn Acosta/flickr)

The Charga-plate. (Photo: Marilyn Acosta/flickr)

Despite the clear advantages of charge plates over a balance sheet, department store cards still had their problems. In 2001, Stan Sienkiewicz, then a researcher with the Federal Reserve of Philadelphia, wrote a report about early credit cards, highlighting the fact that these early versions of credit cards were limited to local businesses. “When a consumer traveled to another part of the country, the convenience associated with these cards was lost,” wrote Sienkiewicz in his report.

The leather case for the Charga-plate. (Photo: Marilyn Acosta/flickr)

The leather case for the Charga-plate. (Photo: Marilyn Acosta/flickr)

The stores actually liked this, however—because it tied consumers to that specific store, ensuring that there was baked-in loyalty. Other types of companies liked that baked-in loyalty as well, creating their own credit card variations and adding new features along the way.

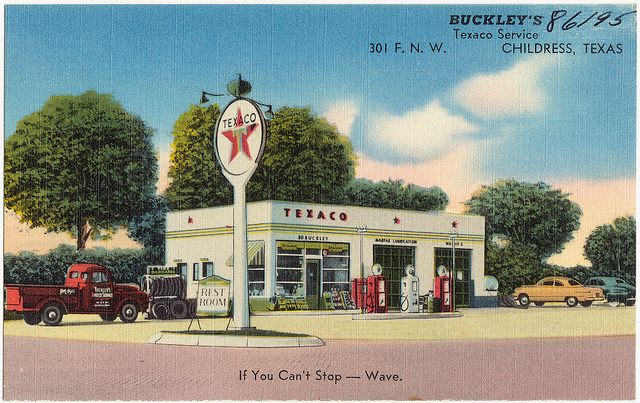

Transportation companies also got in the act. Early gas stations in the 1920s started offering cards of their own, taking advantage of the fact that travelers and commuters need to keep fueling up. Companies like Texaco, in producing their cards, decided upon a slightly better format than the department store dog tags: playing-card-sized pieces of paper. That helped to set a standard size for payment cards.

The airline industry proved to be a major innovator in the credit realm. In 1936, American Airlines started issuing the Air Travel Card,which is generally considered the first “charge card” in history. Over time, it added two key innovations to the credit card model: upon its launch, it utilized a numbering system that tied a specific user to a specific number. Then, in 1969, the Air Travel Card became the first to include a magnetic stripe—doing so more than a decade before mainline credit card providers did the same. (We have IBM to thank for that stripe, by the way.They invented it in the 1960s.)

Texaco offered paper cards for fuelling up in the 1920s. (Photo: Boston Public Library/flickr)

Texaco offered paper cards for fuelling up in the 1920s. (Photo: Boston Public Library/flickr)

The banking industry, surprisingly, didn’t find a lasting path into the credit card game until 1958, when Bank of America created its first national card, the BankAmericard. (Some earlier manifestations existed, but on a local level.) That card is notable not just for being one of the first introduced by a bank, but also for leading banks to work together so they could offer cards of their own. By the 1970s, the card service was spun off, and it became better known as Visa. Mastercard, meanwhile, came along in 1966 as the Interbank Charge Association.

Finally, the technology industry found its way into the game in 1984, when the online service Compuserve began offering an “Electronic Mall” to its members. This service effectively became the first major online shopping service, and—by proving that credit card numbers could be transferred electronically—set the stage for Amazon and company to come along a decade later.

For all the innovations of firms that tripped into handing out credit over the years, the public mostly was familiar with credit cards for decades thanks to the work of two companies: Diners Club and American Express.

The former firm, when it launched in 1950, was primarily focused upon the restaurant industry as a way to allow consumers to pay for their restaurant bills with the help of a monthly bill, rather than being required to carry around cash. It was an idea that saw quick uptake—20,000 people had signed up for the cards within its first year of service.

A common story around the Diners Club is that the company’s founder, Frank McNamara, forgot to bring money with him to a restaurant, but that’s largely considered untrue. American Express, which went after roughly the same kind of market, eventually stepped in and became the big player, usurping Diners Club over the long run. But unlike Diners Club, AmEx didn’t start out as a credit card company. In fact, its history was a lot weirder than that.

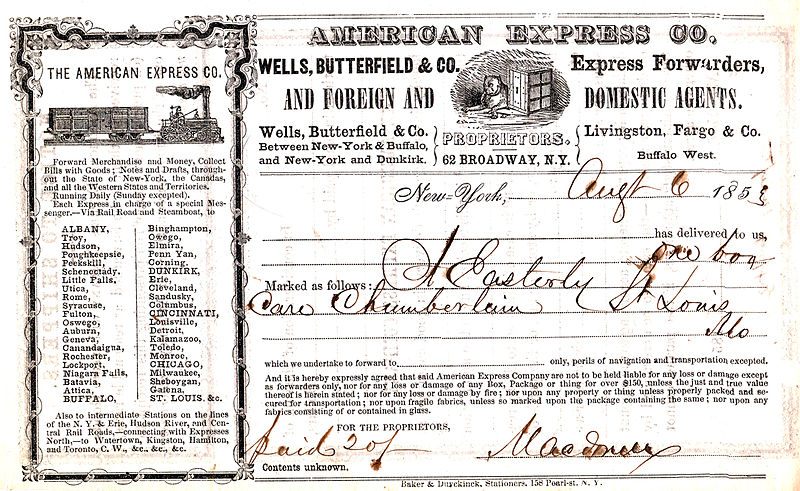

Much like Wells Fargo, American Express got its start thanks to two guys named Wells and Fargo. In fact, it was the same two guys, and there was also a third guy named Butterfield.

Henry Wells, William G. Fargo, and John Butterfield were active in the fast-moving express mail service, with Wells and Fargo often competing against Butterfield. They eventually decided to join forces, forming American Express in Buffalo, New York, back in 1850.

An American Express shipping receipt from 1853. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An American Express shipping receipt from 1853. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

“The express companies served as a lifeline to the growing nation. Intrepid express men, typically on horseback or driving stagecoaches, traversed from the eastern cities to the western frontier, transporting correspondence, parcels, freight, gold and currency, among countless other goods,” the company writes in an article about its history. “American Express quickly earned a reputation as the best in the fledgling industry—the company that delivered, literally.”

(Wells and Fargo eventually started working on offering banking services to the then-budding California market, and that bank became nearly as iconic.)

So how did AMEX get associated with credit cards, anyway? Basically, they found their way to cards through some of their earliest financial offerings—the money order and the traveler’s check. These two products, which are considered as good as money in most places, eventually gave AMEX a pseudo-bank-like status—albeit one that for decades had significant interests in the travel industry—and by the time that Diners Club cards became a big deal, the credit card industry seemed like a natural fit for AMEX, which began to offer its own card in 1958.

A1960s-era Master Charge and Interbank sign. (Photo: Bradley Gordon/flickr)

A1960s-era Master Charge and Interbank sign. (Photo: Bradley Gordon/flickr)

The company’s reach in the travel market ensured that the card could be used in tens of thousands of places, and eventually the company became a massive conglomerate known for promoting an array of colorful cards—first gold, then platinum, then black, now blue.

Many believe mobile payments will be the future of consumer credit, dispensing with the tiny cards. But the newer start-up players have already hit some snags.

First of all, someone needs to tell the American public that there’s a good reason to change. As little as two years ago, the U.S. was projected to do only half as much business in mobile payments as the Asia-Pacific region. Fraud is a big issue. But perhaps the most embarrassing concerns a start-up named named ISIS. For obvious reasons, last September, the firm changed its name to the less-terroristy Softcard.

Unfortunately for them, they decided to do so a week before Apple Pay came out. That was the beginning of the end, and back in March, the firm closed its doors entirely.

A sign for Isis Mobile Wallet. (Photo: tales of a wandering youkai/flickr)

A sign for Isis Mobile Wallet. (Photo: tales of a wandering youkai/flickr)

You can find one relic of this utter failure on eBay,where someone was selling an American Express Serve card with ISIS branding. The card literally says “Serve ISIS.”

A Colorado Springs man was quick to point out the unfortunate nature of the card last year, tipping off a local television station after a shopkeeper noted the unfortunate branding.

“I just want to have people be aware of … this card that’s going around and they’re getting in the mail,”Wayne Davis told KKTV of his gift card. “It shouldn’t say ‘Serve ISIS’ on it, cause that that’s pretty bad … I just don’t want anyone to get hurt over a dumb credit card.”

American Express says it started using “ISIS” on its cards years earlier simply because it liked the name.

Let’s chalk this one up to being yet another weird footnote in AmEx’s long journey through package delivery to plastic discs.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook