Hail Cannons, the Devices That Supposedly Blast Away Bad Weather

They’re startlingly loud and scientifically unproven.

An old-school hail cannon in a castle in Slovakia. (Photo: Etan J. Tal/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Prior to the 1890s, humans attempted to modify the weather using rain dances, prayers, incantations, and bell ringing. Then came an exciting new form of weather modification technology: the hail cannon.

Employed to prevent or reduce hail’s deadly damage to crops, hail cannons can be traced back to an Italian professor of mineralogy, who in 1880 raised the idea of preventing hailstorm formation by injecting smoke particles into thunderstorms via cannon.

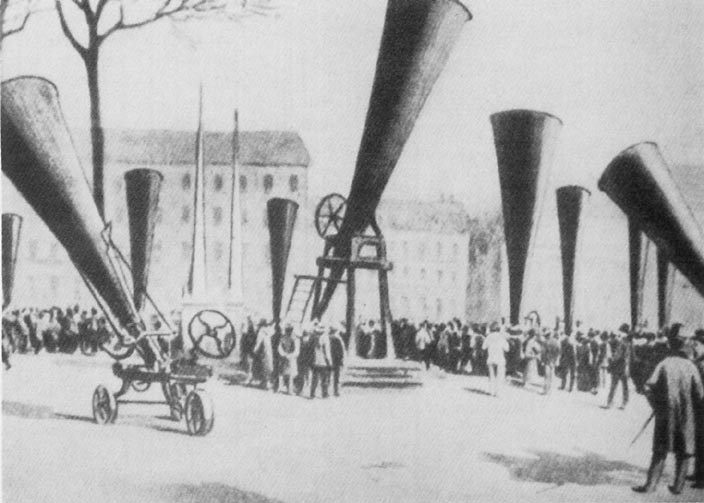

In 1895 and 1896, an Austrian wine grower named M. Albert Stiger conducted backyard experiments, culminating in a muzzleloading mortar pointing upward. The device looked a lot like an oversized, upright megaphone, made of sheet metal mounted on a wooden block.

Upon firing, the cannon would send a smoke ring whistling about 300 meters (984 feet) into the air—the concept being that the discharge disturbed atmospheric motions, forming a strong upward whirlwind that altered the formation of hail in approaching clouds.

Hail cannons were a farming fad in Europe for a short-lived moment, from 1896 to 1905. (Photo: Plumandon/Public Domain)

The first year Stiger tested the cannon, the surrounding area experienced no hail, prompting the swift construction of 30 more machines. The following year, in 1897: again no hail. Interest spiked, and mortars multiplied. Between 1899 and 1900, the number of cannons rocketed; for example, in the Italian province of Venice, the cannon count went from 466 to 1,630.

In 1899, Casale, Italy hosted the first hail suppression conference, followed by three more, which featured the 60 different models and some murmurings of skepticism. Even as enthusiasm spread, and the cannons popped up across Austria, Italy, France, Spain, and Hungary, a few officials were beginning to note inconsistent and unsatisfactory results. Hail cannon hardliners repeatedly wrote off the failures as instances of improper firing, shooting delays, and poor positioning.

By the time the fourth international hail suppression congress came around in 1902, officials had concluded that the cannons’ efficacy was neither proven or disproven. In 1903, the Italian government seized initiative, arranging a two-year experiment involving 222 cannons.

The result? Both testing areas experienced damaging hail, the cannons were publicly declared a failure, and within a few years, they had been mostly abandoned.

A modern-day hail cannon stationed on a farm in Germany. (Photo: ANKAWÜ/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Today, hail cannon technology still lacks any scientific evidence supporting its efficacy—but people continue to make and use the devices. Eggers, a New Zealand manufacturer, sells hail cannons for around $50,000 apiece. According to the company, the cannon works by generating shock waves that disrupt the initial formation of hailstones, turning them into slush or rain. It fires an explosive charge of oxygen and acetylene gas which travels at the speed of sound into the cloud formations above. When a storm is approaching, it goes off every four seconds, and continues firing until the storm has passed.

What today’s hail cannons lack in supporting evidence, they make up for in noise complaints. In 2005, Nissan’s factory in Canton, Mississippi vexed the local community with its “hail suppression cannons,” which purportedly vibrated water droplets before they formed into hail. At the time, the cannons fired automatically when triggered by certain weather conditions, sending loud and repeated sonic blasts into the air for extended periods of time. (According to a CNN report: “Car maker using ‘hail cannons’ at Mississippi factory. Neighbors annoyed.”)

Press play to hear what a hail cannon sounds like.

A few years ago, growing noise complaints from farming communities spurred a student at California Polytechnic State University to write a senior project on “Developing an Advocacy Program for Hail Cannons in Agricultural Practices.” In the 2012 paper, Jacob Diepersloot admits, “It is important to note that hail cannons are not scientifically proven machines.” He then counters, “Hail cannons have shown that they are a viable resource to protect crops from hail damage.” All of the farmers Diepersloot surveyed affirmed that the cannons limited their crop damage.

In an attempt at determining whether hail cannons have any meteorological effect, a reporter at a local CBS station approached the folks at the popular TV show Mythbusters, for their thoughts on the machinery. Jamie Hyneman, one of the show’s scientists, deemed hail cannons “a load of bunk” before noting that “the methodology makes the machine completely untestable.”

So the hail cannon myth, while not busted, continues to have about as much validity as the church bells of yore: both involve humans sending loud noises into the sky in the vain hope of changing the weather.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook