The Gilded Age’s Only Female Tycoon Lived in Brooklyn To Avoid Taxes

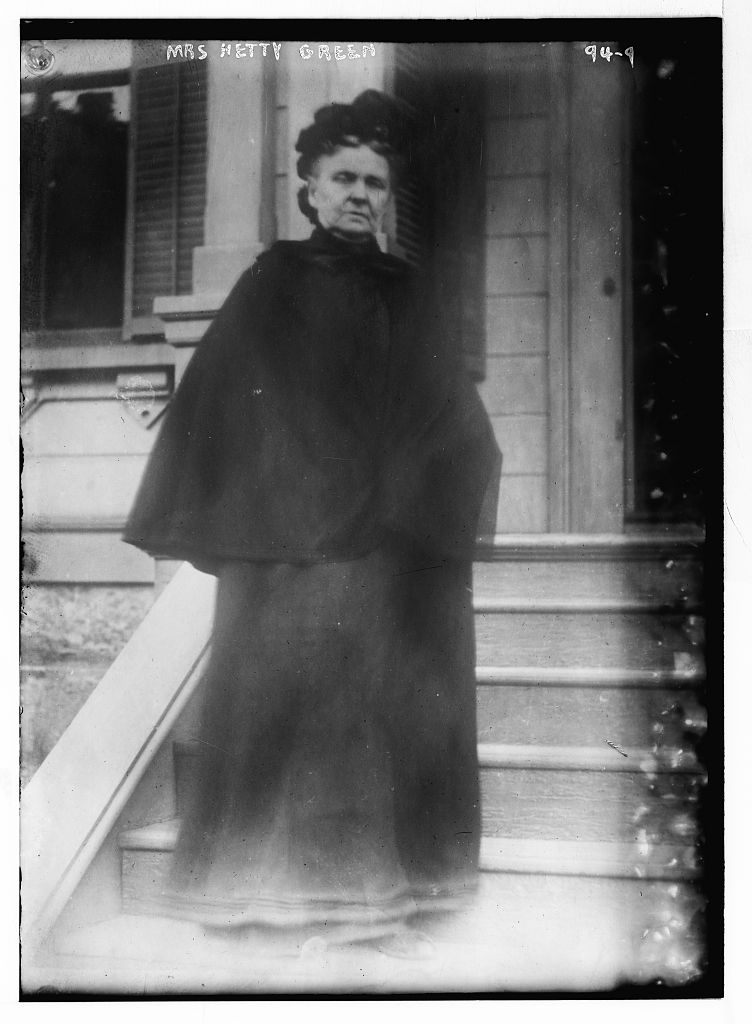

(Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

(Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Hetty Green, the newspapers said, was the richest woman in America.

She had so much money that by 1906, when she loaned New York City $2.5 million at the rather decent rate of five percent interest, she had become the city’s “largest money lender,”the Los Angeles Herald reported. That wasn’t the first time she’d stepped in to tide New York over (in 1898, she had given the city $1 million, at two-percent interest, for a four month bond) nor the last—in the 1908 financial crisis, she’d be there again, ready to lend to the city money.

As often as she helped the city through financial tough spots, though, Hetty Green never officially lived there. Long before it was cool or respectable, especially for New York’s elite, Hetty Green lived in Brooklyn.

In the Gilded Age, when fortunes were being made and flaunted, Green stood out in two ways: she was a woman—the only notable female financier of her time—and she didn’t like spending her money. In her 20s, she had inherited more than $5 million of the money that her Quaker father had made in whaling; when she died in 1916, she left more than $100 million. In today’s dollars, she would have been a billionaire. She made her money in railroads and real estate (at one point she owned large swaths of Chicago), and she was fanatical about not spending it, so much so that the Guinness Book of World Records named her “World’s Greatest Miser.”

Green was famous for her frugality but jealous of her privacy, partially because she resented reporters for telling tall tales about her and partially because she was paranoid. (She worried she might be assassinated.) She also had a reputation for meanness: she allegedly pushed her aunt’s favorite maid down the stairs, and it was rumored that when her son’s leg was injured, she took him to a free clinic, meant for people who couldn’t pay doctors. In her biography of Green, the writer Janet Wallach takes pains to argue that Hetty’s eccentricities were much maligned and exaggerated, mostly because she was a woman—that if she had been a rich man who dressed plainly and tried to save money, no one would have made much of it. But whatever the reason, Green’s actual life was not as clearly documented as her finances, making it hard to tease out which rumors about her are real and which are exaggerations.

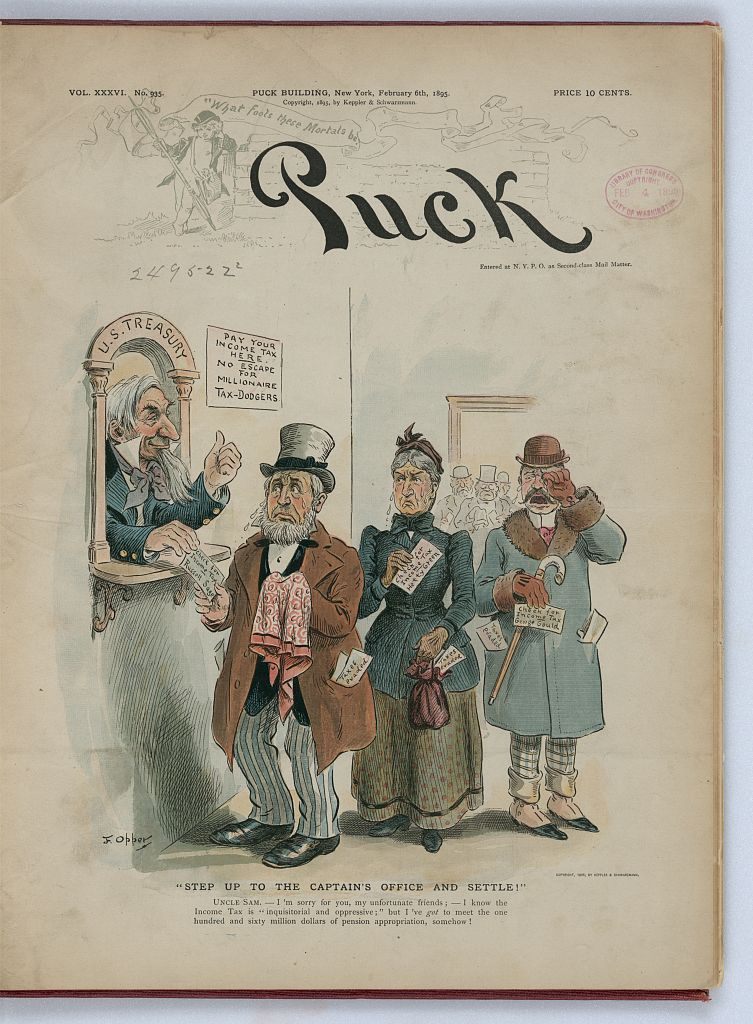

(Photo: Library of Congress)

It is certainly true, however, that after she and her husband separated and she moved to New York from their home in Vermont, Hetty Green did not do what most millionaires would have—buy a mansion on Fifth Avenue or some other tony area of the city. Instead, she lived in inexpensive hotels and boarding houses in Brooklyn, usually under assumed names, and paid $23 to $60 per month—that’s somewhere between $600 and $1,500 in today’s dollars and far less than she could have afforded, had she wanted to spend more. It’s as if Michael Bloomberg decided to live Ridgewood, Queens, to save money.

Green commuted daily to a desk at the downtown Manhattan bank that held her money and securities, and initially she favored Brooklyn Heights. “She has a modest room in a comfortable boarding house on Pierrepont Street, and lives in a quiet, unpretentious manner,” the Brooklyn Eagle reported, according to Wallach. Later, Green moved to Hotel St. George, on Pineapple Street, and for a while lived on Henry Street. She usually took public transportation downtown, and, as the Eagle wrote in 1893, most of the middle class people who passed her on Brooklyn’s streets had no idea she was one of the world’s richest women.

Green’s preference for Brooklyn, though, was a way to save money—and not just on rent. Much like today’s wealthiest people, Green preferred not to pay New York City’s high taxes, and she moved around in order to avoid establishing residency in any one place. Her attachment to Brooklyn lasted only as long as the tax advantage did: in 1898, when the five boroughs became one city, Hetty Green left Brooklyn for Hoboken.

Illustration from an 1895 issue of Puck magazine, showing Hetty Green, Russell Sage and George J. Gould standing in line and crying as they pass their income tax checks next to a notice that states ”Pay Your Income Tax Here - No Escape for Millionaire Tax-Dodgers”. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Even in New Jersey, though, Green moved frequently (in part to avoid the press). Only once in her life did she really make a concession to society’s expectations for a rich woman: when her daughter, Sylvia, was becoming engaged, Green moved the two of them to the Plaza Hotel for a short time. Once Sylvia was married, though, Green went back to Hoboken. New York wanted to believe that the luxury there had swayed her: In 1909 year, the New York Times reported that Green was thinking of finally buying a proper Fifth Avenue property.

“The story was that Mrs. Green had again grow tired of her Hoboken flat…The new house was to cost $650,000,” the paper reported. But it wasn’t true: “Mrs. Green, in Hoboken last night, said she had no intention of moving to Fifth Avenue.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook