The Beetle That Goes Undercover to Steal From Foraging Ants

The high-risk, high-return antics of the parasitic highwayman beetle.

The jet ant’s working day is long, unfettered by union codes or health and safety regulations. The hours are unlimited, rest comes only in the form of hundreds of tiny power naps to propel them through the drudgery of their instinctual labor. Worker jet ants go out into the wide world (they range across Eurasia) to forage for honeydew from little insects such as aphids. When they find it, each fills its social stomach—part of the esophagus—with this sugary liquid. Next, like a bucket brigade, one worker ant pukes its sweet cargo into the mouth of colony-mate, who passes it onto another until the spoils of their labor make their way back to the nest (a process called trophallaxis).

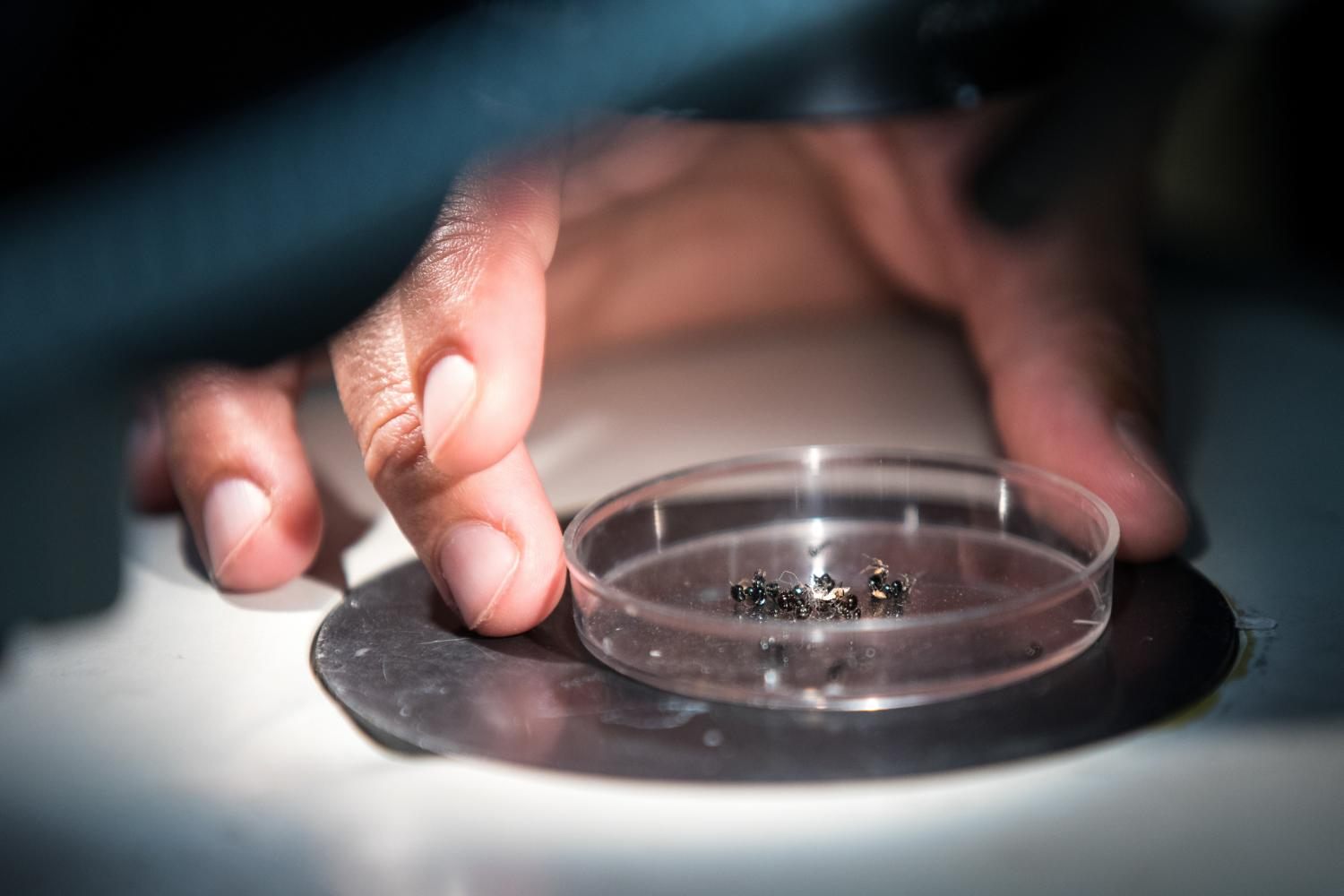

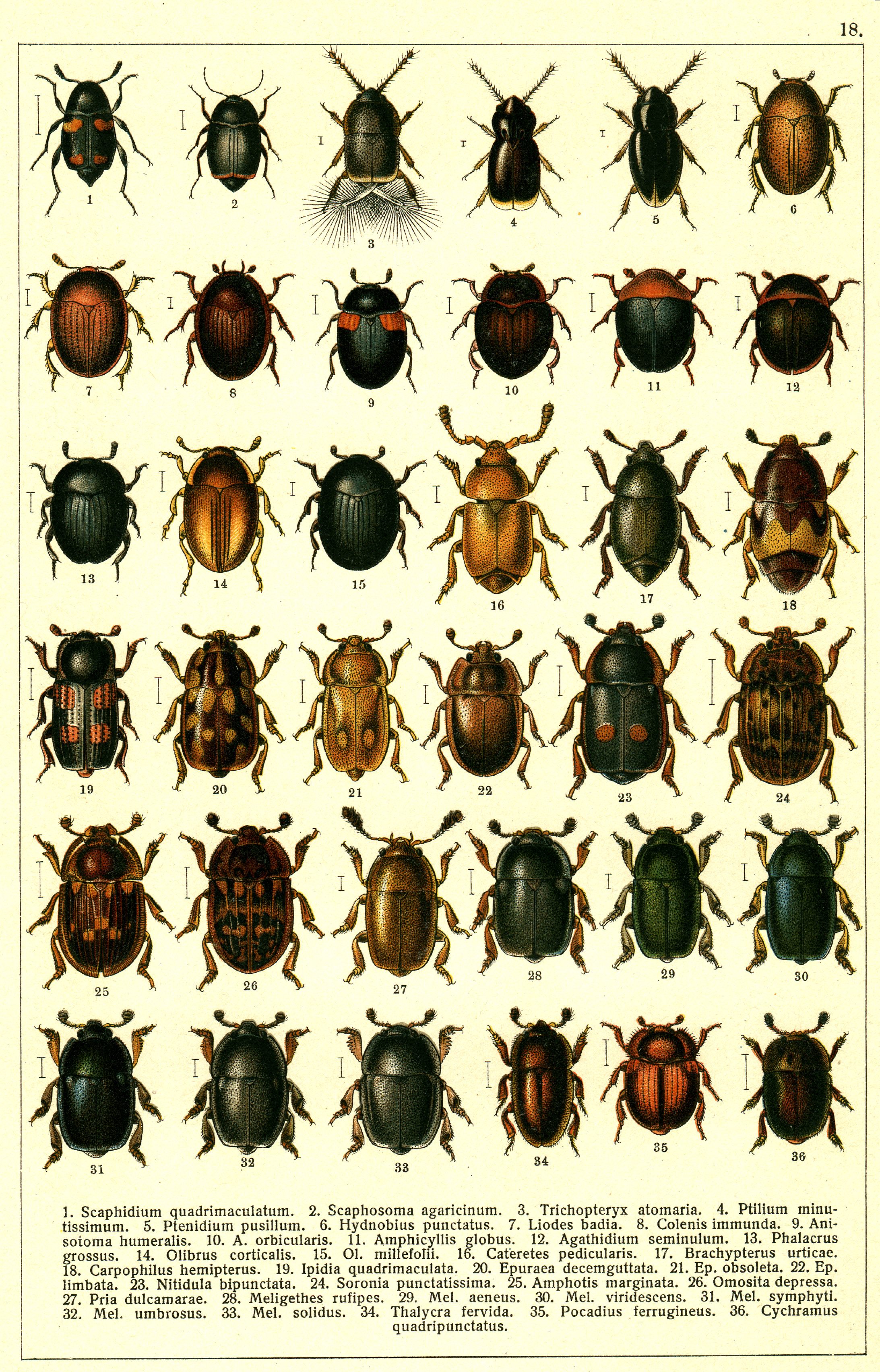

But there’s a sleeper agent that undermines this smooth operation: the nitidulid beetle, also known as the highwayman beetle. It risks life and limb by posing as an ant—exploiting their low-resolution eyesight and, likely, the bleary fug of months of working through the night—to steal food from the ants’ very mouths. The behavior of these parasitic bugs is under investigation, in a new journal article by Arizona State University researchers Bert Hölldobler and Christina L. Kwapich, in PLoS One.

The beetles hover at the entrance of the nest, waiting for foragers to return with their sugary booty. “Let me take that off your hands!” they suggest. Glands around their heads and mouths secrete a mysterious “appeasement compound” that distracts the hapless worker ant. “At the beginning of the interaction, where the food stealing is happening, the ant is transfixed by the secretion,” ASU postdoctoral researcher Christina Kwapich told ASU Now. The ant then leans in and gives the undercover agent everything it’s got—1.8 times as much honeydew as it would pass on to an ordinary coworker.

Workers inside the nest are more skeptical of these intoxicating strangers. And when their tricks fail, things can rapidly go south for the beetle. The punishment dished out to the thief by the ants is a brutal one. First, they try to flip the interloper over, and if they succeed, they tear off its antennae and legs—a slow and unpleasant demise. Fortunately for the beetle, Kwapich said, its hairy legs sometimes allow it to grip the ground and prevent this initial flipping. “When an ant perhaps notices the beetle isn’t an ant, the beetle can really suction itself to the ground. It makes a perfect little cup on the ground that’s difficult to pry up.”

As any successful embezzler knows, the key to success is not gumming up the works enough to get caught. The highwayman beetle seems to have figured this out, Kwapich said. “It’s not occurring at high enough numbers to affect the success of the colony.” The ants march on, and on, and on, for the good of the collective, while the highwayman is out only for itself.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook