How a Forged Sculpture Boosted Michelangelo’s Early Career

Fake it ‘til you make it.

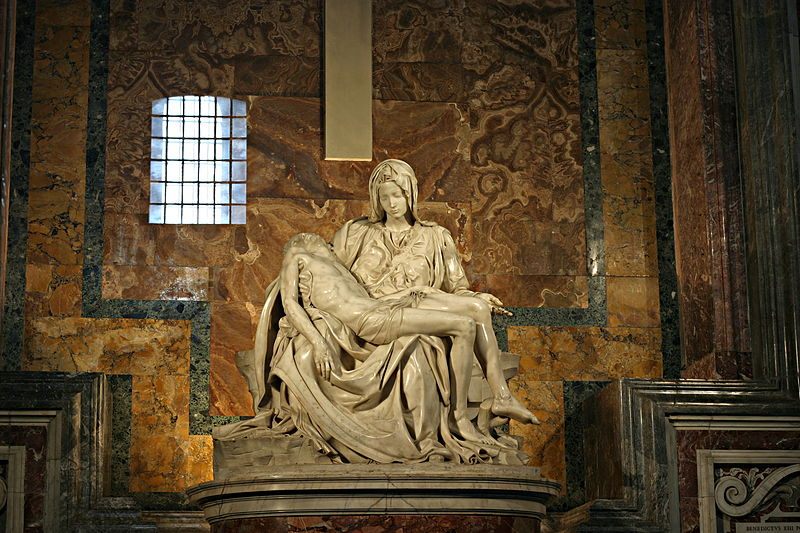

If you’ve seen any of Michelangelo’s artworks in person, you have probably felt the same awe that millions of pilgrims to the Sistine Chapel have experienced, while staring up at his singular ceiling frescoes. With masterpieces like the Pieta and the astonishing statue of David, he is decidedly one of the most influential artists in the history of the western world. But what most people don’t know is that, at the beginning of his career, Michelangelo was a forger.

In his teenage years, he was a protege of Lorenzo de Medici—also known as Lorenzo the Magnificent—and studied under some of the most respectable sculptors of the time. In his circle, he quickly gained a reputation for talent that went far beyond his years and experience.

But despite his promising future, back in 1496 he was just another starving artist trying to find ways to fund his art. At 21, he had the talent and the passion, but not the name necessary to sell his work at a profitable price. He was also working in Florence at the beginning of the Renaissance, when many art collectors were more fascinated by the idea of possessing some of the classical sculptures that were just beginning to be unearthed, than in acquiring contemporary art.

Faced with this dilemma, Michelangelo opted for the seemingly logical solution: he forged a classical sculpture by artificially aging it.

Or so one version of the story goes. In The Lives of the Artist—considered the first art history book of the western world—Giorgio Vasari complements this version with another one: Instead of Michelangelo, it was the art dealer Baldassari del Milanese who took the sculpture, which depicted a sleeping cupid, and buried it in his vineyard in order to age it.

Whether it was Michelangelo’s or Milanese’s idea, the statue was artificially aged and successfully sold as an antiquity to an Italian Cardinal named Raffaele Riario. Everything went according to plan until the victim of the pair’s astuteness became aware that he had been duped.

One could assume that the Cardinal’s hurt ego and depleted wealth would incur his wrath against the young artist. It seems, however, that his indignation was centered on Milanese, who had to give his part of the money back. As for Michelangelo, not only was he able to keep his cut, but he also received an invitation from the Cardinal to come to Rome, an opportunity that proved essential to his career.

Why would the Cardinal reward the artist who had taken him for a fool? To fully comprehend this attitude, it is necessary to grasp the artistic environment of the time. According to art historian Noah Charney, author of The Art of Forgery, far from valuing originality, Renaissance patrons of the arts admired artists who could reproduce the works of their masters. A good imitator proved that he had true potential. Therefore, being able to forge an ancient Roman statue showed the incredible talent Michelangelo had. Rather than hurting his career—as it would now—it helped propel him to fame.

As to the fate of the sculpture, it was returned to Milanese, the shady art dealer who had sold it. Reportedly, when Michelangelo asked for it back, the dealer refused, saying he would smash it to pieces before returning it. Instead, he sold it again, and kept all the profits. From there, the sculpture moved around, as it was sold or gifted to new owners, and even taken as a bounty in the sacking of a palace.

At some point in the late 17th century, the sculpture was transported to England, where it disappeared. The treasure is believed to have perished along with countless other priceless pieces in the devastating fire that reduced London’s Whitehall Palace to ashes. Once the largest palace in all of Europe, the splendid Tudor house was brought down by a linen that was left to dry close to a fire. This was the last anyone saw of Michelangelo’s controversial cupid.

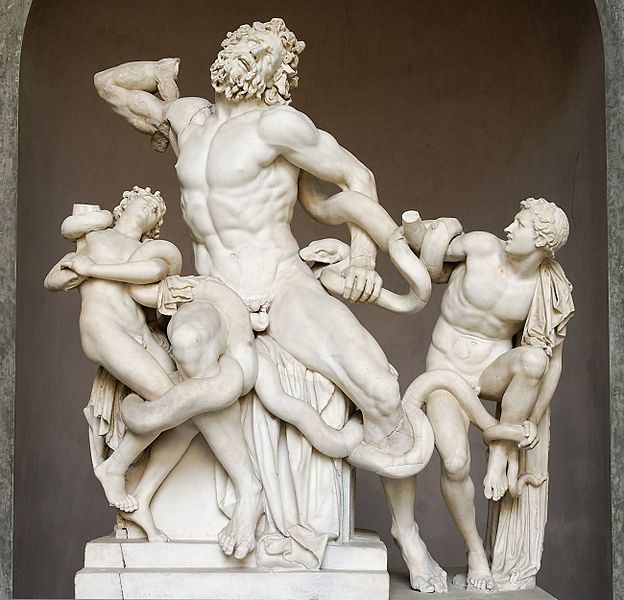

No other verified forgeries are known by this Renaissance master, though his past has aroused suspicion about the authenticity of other great works. The famous statue of Laocoön and his Sons has been viewed as a stunning sculpture from Greek antiquity since its discovery in 1506. Now, art historian Lynn Catterson is spearheading an investigation on whether the sculpture could be another one of Michelangelo’s forgeries.

The suspicion arose not only because there are early sketches from the artist that resemble this statue, but also because it was unearthed from the backyard of one of his close friends. This coincidence resulted in Michelangelo being commissioned to restore the sculpture. Though the legitimacy of the claim has been heavily questioned, there is no doubt that the great artist’s less enviable past life has followed him.

In the eyes of the world, however, Michelangelo is the embodiment of a true artist, so much so that the adoring public seems to have turned a blind eye to the less inspired works he created at the beginning of his career.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook