The Story Behind the Bulletproof Photo Craze

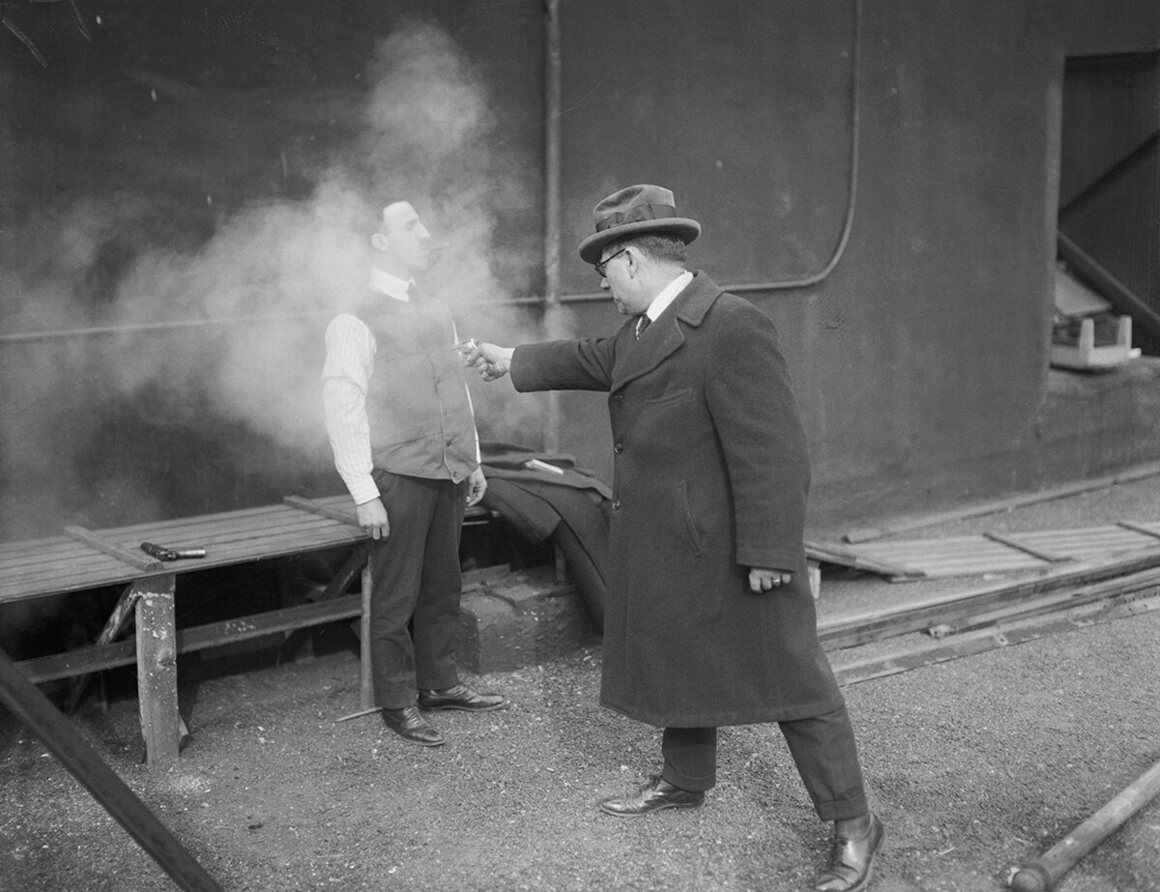

Men shot each other all the time, it seems, for publicity photos in the 1920s.

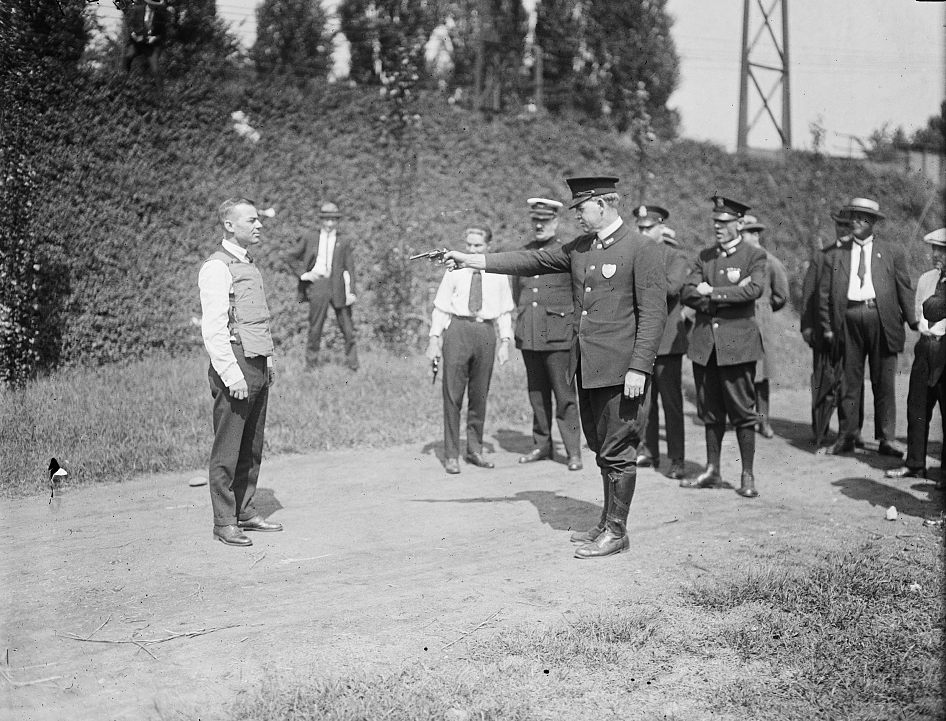

Testing a bulletproof vest in New York City, c. 1920s. (Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images)

On March 15, 1922, a news photographer captured this image of Leo Krause getting shot at close range near Carnegie Hall. Krause wasn’t a murder victim, though—he was a salesman who travelled the world demonstrating the death-defying superpowers that his patented bulletproof vest gave him. This was one of the first of more than 4,000 bullets he’d later estimate he’d been shot with in his 27-year career. And he knew that arresting images like this were the key to more sales.

Before internet memes, before Reddit, even before performance artists like Chris Burden took aim, swaths of vest salesmen hawked their wares with such proto-viral stunts. Prohibition-era mobsters and gangsters were increasingly turning to gun violence, and newspapers regularly printed photos of tests of bulletproof clothing and bulletproof glass. Here’s W.H. Murphy of the Protective Garment Corporation demonstrating his wares to a Maryland deputy sheriff:

Demonstrating a bullet-proof vest, c. 1923. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-hec-43388)

But the origin story of the bulletproof vest is far more complicated than readers at the time knew, and it was an image in a popular magazine that started the deception.

The February 15th, 1902, edition of Scientific American arrived bearing great news: ingenious inventor Jan Szczepanik, often referred to in the press as the Polish Edison, had recently unveiled the first “bullet and dagger-proof waist coat” out of tightly wound silk. As a result, the recent plague of assassination attempts against presidents and monarchs would no longer be as deadly. (“Such an effect would indeed be most beneficial,” the magazine drily noted.) The article went on to describe the vest’s effectiveness:

“Highly impressive and dramatic are the firing tests upon a live person, who, in the consciousness of his invulnerability, calmly and without moving a muscle exposes his breast, protected by the wonderful silk fabric, to the otherwise death-dealing bullets…The bullets rebound from the vest like hailstones from iron armor and drop to the ground with the point flattened.”

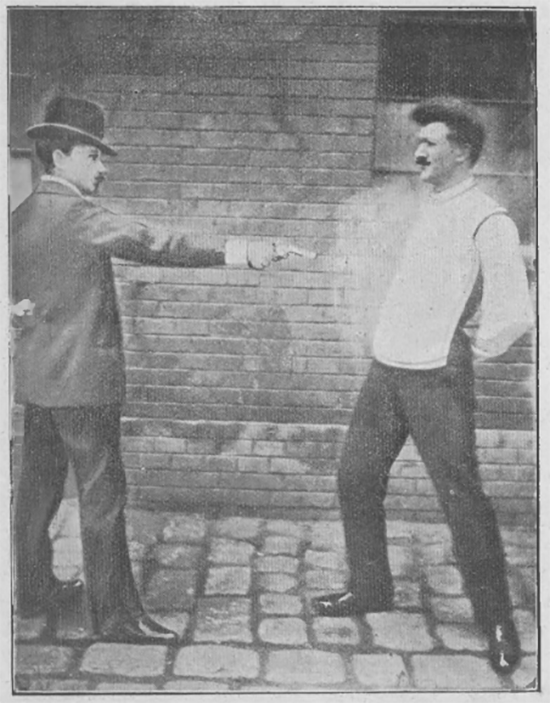

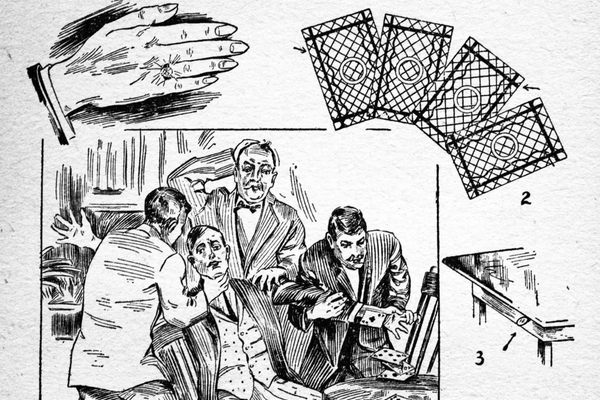

To drive the point home, the magazine included a soon-to-be iconic illustration of a dapper gentleman thrusting his vest-covered belly toward another top-hatted man who is firing a revolver at him from just a couple of feet away. It’s the first image of a bulletproof vest in action, and one of a series of bulletproof-vest-testing images that captured the public’s imagination during the early days of the 20th century.

Mr. Borzykowski shooting at Joseph, assisting in a bullet-proof armor. (Photo: Courtesy Slawomir Lotysz/ Ilustracja Polska, vol. 6, 1901/ Public Domain)

What Scientific American likely didn’t realize, though, was that by printing the image and the article, they were publishing Szczepanik’s propaganda. As a result of that bit of good PR, even today Szczepanik is often credited with inventing the bulletproof vest. As it turns out, though, he stole the glory from a Chicago-based Polish priest named Casimir Zeglen.

For the last decade, Slawomir Lotysz, a professor at the Institute for the History of Science in the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, has combed through archival Polish-language correspondence and newspapers to better understand the relationship between Zeglen and Szczepanik. A few years ago, he discovered an archive of Zeglen’s letters in Rome, which revealed the depths of the Polish Edison’s deception. Of course, casting doubt on Szczepanik in Poland is like trying to do the same about Edison here in the States. The Warsaw Museum of Technology recently hosted a special exhibit about the inventor, and he was recently honored with a stamp. “I am hitting a wall with my head here, in Poland, trying to tell the people truth about Zeglen,” Lotysz tells me. “Szczepanik is a statue—a hero as you say.”

Lotysz laid out the timeline for the development of the bulletproof vest in a 2014 paper in the academic journal Arms & Armour. It turns out that Zeglen the priest first got the idea to create a bulletproof garment in 1893, when Carter Harrison, Sr., the mayor of Chicago, was shot dead on his doorstep by a paranoid newspaper distributor. Zeglen had only recently been assigned by his church to minister to the huge Polish community in Chicago, and he was determined to do something about the violence in his new country. By 1897, he had patented his new method of weaving silk into layers thick enough to stop bullets; the world’s first soft armor. That same year, he started giving live demonstrations of his new technology. He’d don a vest and then have a soldier shoot him with a 7 mm pistol.

It was such a sensation that later that year, he took his show on the road to New York. Demand for his new vests became so great, though, that he realized that he needed to go to Europe, where the first mechanical weaving machines capable of creating large numbers of vests existed.

He first met Szczepanik in Vienna in early 1898, just after the inventor had been labeled a genius by none other than Mark Twain for devising a proto-television known as a telectroscope and a new process of mechanically applying images to fabrics. Szczepanik had the automated weaving technology to create Zeglen’s vests at scale, so the men signed an agreement and Zeglen returned to the States to keep marketing his invention.

For the next three years, Zeglen toiled in relative obscurity as he tried and failed to convince police departments to buy his incredibly expensive silk vests. But then, in 1901, a son of Polish immigrants caused the demand for bulletproof vests to go way up. That September, at an exposition in Buffalo, New York, the anarchist Leon Czolgosz walked up to President William McKinley and shot him twice in the stomach with a revolver. The president died eight days later.

Szczepanik immediately realized the impact the assassination would have on the bulletproof vest business, and decided to use his fame to muscle Zeglen out of the business. The first press he got was from the Polish magazine Ilustracja Polska, which likely commissioned the engraving above. The caption states it’s an image of Benno Borzykowski, Szczepanik’s partner in the textile industry, shooting his assistant Joseph in the backyard of his factory in Vienna. The arresting image was then picked up by the popular German weekly Illustrirte Zeitung before appearing in Scientific American a few months later.

When Zeglen saw the onslaught of publicity that completely failed to mention him, he was irate, according to Lotysz, the Polish historian. He travelled back to Poland to show off his patents and (unsuccessfully) attempt to convince the public that he was the true inventor of the revolutionary technology.

The final split between the men occurred in 1904, when Zeglen attempted to sell his technology to the Russian army, only to learn that Szczepanik had already visited them.

What eventually quieted the controversy, though, wasn’t publicity. It was technology. While silk was strong enough to deflect the bullets in 1900, in the ensuing years guns became much more powerful. By 1910, silk was no longer an effective barrier and the invention was useless. Szczepanik landed on his feet, becoming a Polish icon after inventing dozens of other items, from automated film to an electric rifle to a submarine. When Zeglen returned to Chicago to rejoin his church, though, the bulletproof monk found that after his long time away, his fellow clergymen no longer wanted him there.

Zeglen’s silk wasn’t strong enough to be effective by itself, but other inventors continued to search for new materials they could put in between bullets and human flesh. Leo Krause, for example, found he could create enough tensile strength to stop even more powerful bullets by creating a quilt of silk and overlapping metal plates. And with this new technology, he and others went out in the world seeking publicity and spreading the word one gunshot at a time.

Bonus:

We’ve partnered with our friends at Dinner Party Download to bring you an audio segment about this story—and a drink inspired by the priest and his silken vests.

Below is the cocktail recipe, The Father’s Bullet:

Locked and loaded by Kate Jerome, bartender at The Bedford in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood, where Father Zeglen’s former church still stands.

Ingredients:

2 ounces Bulleit Rye Whiskey (obviously)

1/2 ounce of Bénédictine (an herbal liqueur made by monks)

1/2 ounce pickled beet juice (to represent the color of sacramental wine and church. It’s also the color if the vest didn’t work…)

1 ounce lemon juice

1 lemon (for garnish)

Dash of orange bitters (to represent the bitterness Father Zeglen might’ve had in his heart after Jan Szczepanik got credit for the vest)

Instructions:

In a cocktail shaker add ice, Bulleit Rye Whiskey, Bénédictine, beet juice, lemon juice and orange bitters. Shake and then strain into a rocks glass with a large ice cube. Take three lemon twists, braid them together and wrap the braid around the ice cube like a little vest (or headband?) protecting the cube.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook