How America Joined Its Two Great Loves, Cars and the Outdoors

Auto camps were all the rage in the 1920s.

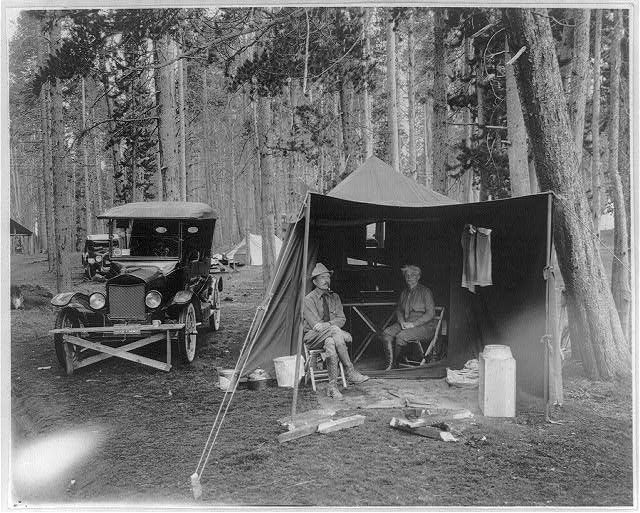

Camping at Lake Public, in Wyoming. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-41022)

One summer weekend in 1921, President Warren G. Harding went car camping. He rode out to western Maryland, where a fleet of cars awaited: under a soaring white tent, the president dined in the wilderness with Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and the other “Vagabonds,” who had spent every summer since 1914 exploring the country in a caravan of cars. Each year, their set-up grew more elaborate: in 1919, their camping trip required 50 cars, including one specially built to keep their food refrigerated.

Each year, the group picked a different destination. They might wander through the Smokies or up into the Adirondacks, or across New England, enjoying the outdoors and each others’ company around the campfire. And while the Vagabonds set-up might have been luxe for the era, they were enjoying the pinnacle of a fad that was sweeping America.

For a few short years, from about 1913 to the early 1920s, auto camping was all the rage. As new owners of automobiles, Americans were learning what it felt like to get in their cars and drive, away from the city, away from responsibility, away from real life. Although this trend lasted just a few years, it laid the groundwork for the ways Americans would travel for years to come: auto camps were the precursor to both motels and RVs.

Warren G. Harding dining with the Vagabonds. (Photo: Library of Congress)

“Auto camping began as an anti-institutional sport,” writes Warren James Belasco in Americans on the Road. The very first people to car camp did not want to commit to plans or destinations, so they packed gear that would let them feel at home wherever they happened to stop for the night.

They also realized that, with roads outside of cities still questionable, they might have no other choice. Early auto travelers would pull over the side of the road, perhaps on the edge of a farmer’s field, unfurl their tents and make themselves at home.

By the early 1910s, car travel was becoming common enough that farmers were becoming less hospitable to roadside campers, but cities and towns were looking to attract them. In 1913, the first year car ownership in America topped one million, Douglas, Arizona, opened the first city-run auto camp.

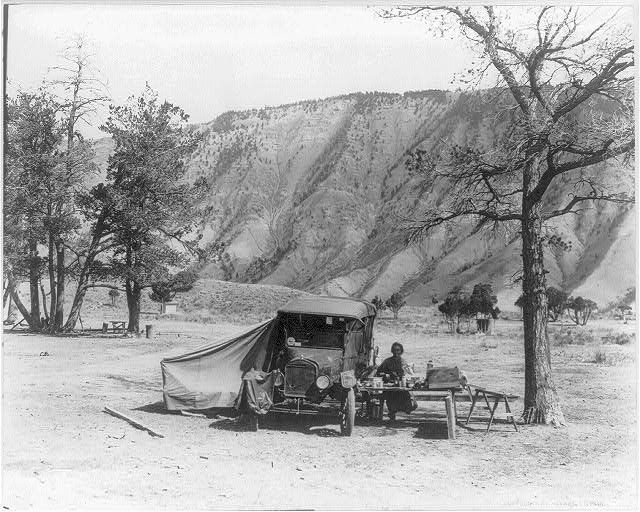

Car camping in Yellowstone. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-47337)

These auto camps began as simple affairs. They were located in parks or pleasant places outside of town, and each car occupied a designated area. There was a sense of camaraderie among campers, who gave each other “camp names” rather than asking for formal names and digging for details of life back home.

Soon, though, camps started competing to attract travelers. “It was like an arms race of amenities,” says Stephen Mark, the historian at Oregon’s Crater Lake National Park, who has researched the region’s auto camps.

Overland Park, in Denver, was the acknowledged leader: it was “the Manhattan of auto-camps,” with a three-story building at the center offering places to shower, cook, and do laundry. There was a grocery store inside, too, as well as a barber shop. In one season, more than 7,800 cars might come through this camp. One year, according to Places Journal, campers came to Overland Park from every state except Delaware.

Auto camp in 1923. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-npcc-24525)

By the 1920s, there were thousands of auto camps—one estimate puts the number somewhere between 3,000 and 6,000—and more than 10 million people trying out life on the road. Where once camps were free, some started charging a small fee for nightly use, and privately run camps opened to compete with municipal ones.

Soon, more permanent structures, usually small, flimsy cabins, were going up on campgrounds—no tent needed—and “motor hotels” that catered to auto travelers began pulling away campers who had never been that enamored of sleeping on a cot bed in the first place.

At the same time, camps started making accommodations for car campers who couldn’t fit all their gear in a normal car and wanted to bring a trailer along with them. Within about two decades, Americans had gone from camping on the side of the road to inventing car camping, motels, and proto-RVs.

A trailer in an autocamp. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-fsa-8a02653)

The original auto camps, so beloved in the 1920s, mostly disappeared during the following decades. In the 1930s, when more people were traveling to find work than to find leisure, auto camps gained a reputation as places where migrants workers would gather, as opposed to relaxing vacation spots.

Overland Park closed in 1930, and by the end of the decade, J. Edgar Hoover was excoriating tourists camps as the “new home of crime in America.” Visit one of these spots, he warned, and you risked a brush with “disease, bribery, corruption, crookedness, rape, white slavery, thievery and murder.”

Today, the best bet for visiting a classic auto camp is in Glacier National Park, which has two camps on the National Register of Historic Places. Any others that linger on are little recognized. “They tend to be unconsciously preserved,” says Mark—meaning they remain not because of any historic value but because they’re still in use.

Most of these camps, though, are ghosts. In Ashland, Oregon, where there were once camps with running water, gas stoves, electric lights, playground, wading pools, and a regular laundry wagon, one site became the park office. “You have to look really closely, but if you’re on the site, you can see where the municipal camp once was,” says Mark.

Auto camps left their mark in other, more intangible ways, though: they changed the way Americans thought about traveling the open road and exploring the country.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook