How Nigerian Romance Novelists Sneak Feminism Into Their Plots

A still from the movie version of So Aljannar Duniya, the first work published in Hausa by a woman. (Image: Youtube)

Say you’ve run into a spot of trouble–some relationship issues, or family drama, or your friends are angry at you. Or maybe it’s worse–you’re in a discriminatory situation, or even a dangerous one. You need help from someone smart; someone who really gets it. Who do you turn to? If you’re living in Kano, Nigeria, you’ll probably do the opposite of what you’d do anywhere else. You’d pick up a romance novel.

Littattafan soyayya, or “books of love,” are a special kind of soapy fiction unique to Kano, Nigeria’s second-largest city. Written and read mostly by women, the works deal with issues ranging from living with HIV/AIDS to fighting for your education to marrying young, all wrapped in a love story and bound in brightly-colored covers emblazoned with smiling female faces. Authors publish the books through collectives, and sell them to their thousands of fans at roadside stands and market bookshops–in the same markets that, lately, are better known as attack sites for suicide bombers.

To Western readers, the phrase “books of love” brings to mind bare-chested Harlequin clones gazing soulfully out from supermarket checkout racks. But littattafan soyayya is less Danielle Steel and more Leo Tolstoy. Though generally serialized into small, affordable pamphlets, like Victorian novels once were, complete works are often 500 pages or more, says Dr. Carmen McCain, a scholar of Hausa film and literature at Kwara State University Malete in Nigeria. The characters need this much space to achieve their creators’ myriad purposes. Over many chapters, your average littattafan soyayya protagonist may lose and find love, but she also might deal with intergenerational conflict, seek an education, or learn how to strive for equality in her marriage.

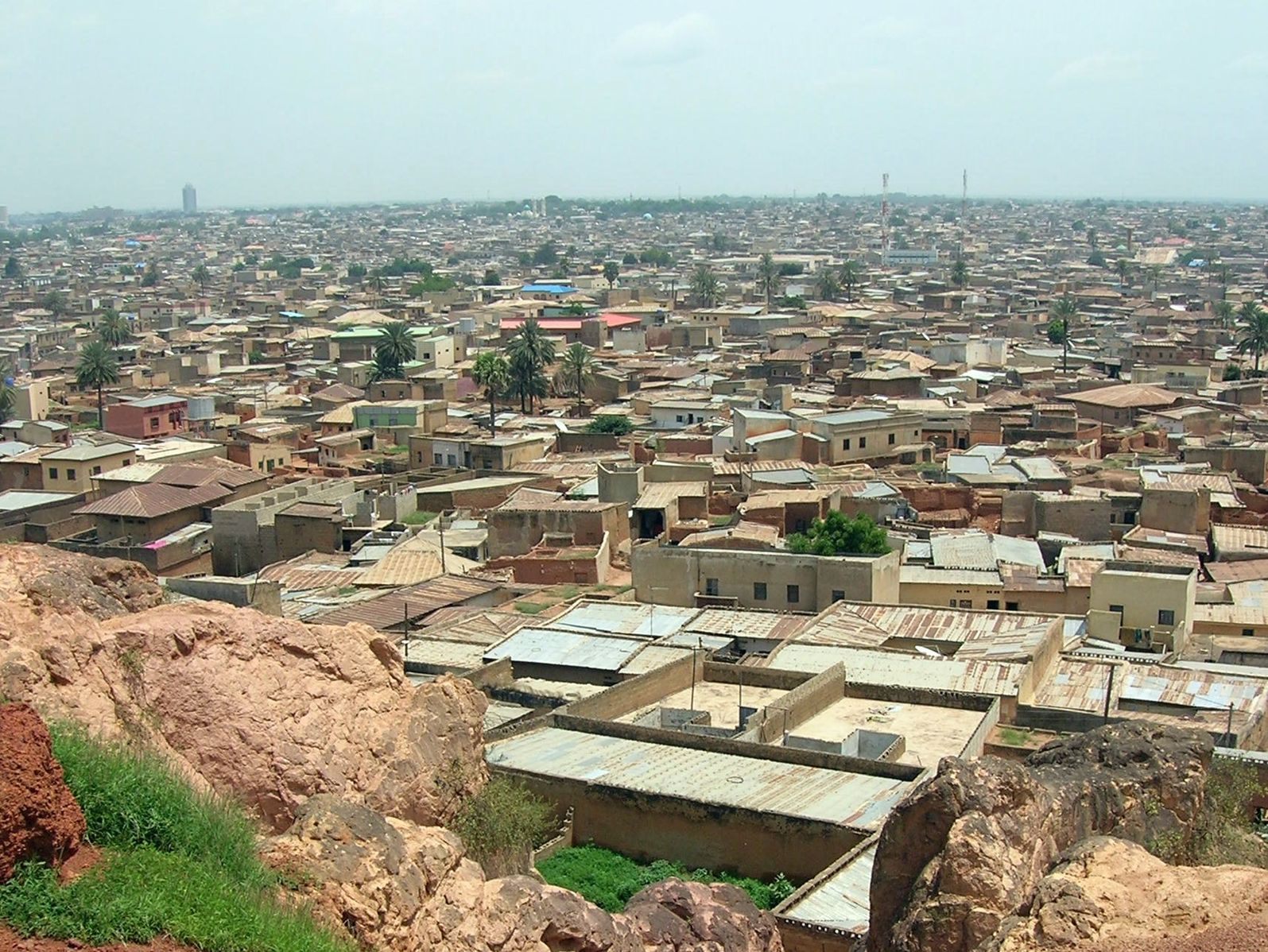

An aerial view of Kano. (Photo: Shiraz Chakera/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

This genre is a subset of Kano market literature–a broad term that encompasses the many and diverse works written in Hausa, a language native to Nigeria. Browsing the markets today, you can find everything from thrillers to highbrow novels to mythical adventure fantasies. “I’ll see people in taxis and at weddings and on film sets reading novels,” McCain says. “You see them quite a few places.”

But, as scholars Graham Furniss and Abdalla Uba Adamu wrote in a 2012 paper, this now-thriving scene grew out of collapse. In the 1980s, they explain, the Nigerian economy crashed, and traditional publishing outlets crumbled along with it. This put Hausa writers in a perilous financial position–but instead of capping their pens, they circled up, forming writing groups and self-publishing their works with the help of a new tool, the personal computer.

A decade into this new business model, “a number of novels began to focus on the boy-girl relationship, demurely and within a framework of Islamic propriety.” But it wasn’t until 1980 that the subgenre really took off, thanks to So Aljannar Duniya (roughly, “Love is a Paradise on Earth”), an interracial romance that won a writing contest and was formally published. In the words of Furniss and Adamu, it was this book that “really set the world alight to [Hausa] love-story writing.” The author, Hafsat Abdulwaheed, was the first woman to ever publish a book in Hausa.

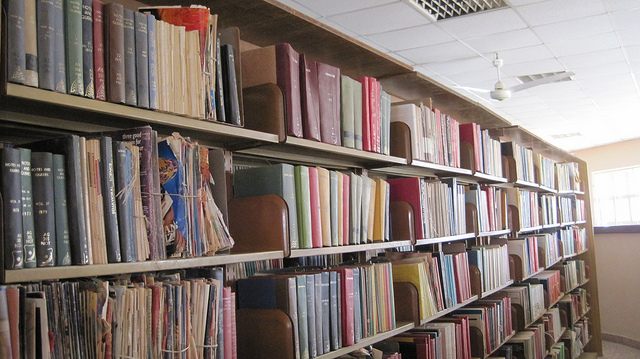

Bookshelves at Bayero University in Kano. (Photo: Michael Sean Gallagher/Flickr)

Fast forward to the 2010s, and, as editor Rakesh Khanna writes in the introduction to a Hausa work, female writers “now dominate the field.” Some of these women live in purdah, a Muslim tradition that dictates married women stay indoors at almost all times. A few are presences in Kano’s thriving movie scene, Kannywood, where they write and direct screenplays based on their novels. Some are members of Kano’s many writing groups, while others “are just kind of writing at home” and getting publishing help from friends, says McCain. Regardless, they dedicate their free time to writing complex, multi-part stories for their fans–younger generations of women who, Khanna writes, “make up the bulk of the readership.”

“The books are often credited as being partly responsible for the marked rise in literacy among Hausa women,” says Khanna.

For many of the most influential littattafan soyayya authors, this was all part of the plan. Bilkisu Salisu Ahmed Funtuwa, a prolific and bestselling member of the scene, told an interviewer she is galvanized by the difficulties women face when marriage interferes with their schooling. “I realized that through the medium of writing, using the little talent God gave me, I could put into the heads of these girls ideas–through entertainment and enlightenment–to appreciate the importance of education,” she said.

In Funtuwa’s works, even plot points that might seem shallow at first glance are, in the context of the novels, suffused with larger issues. For instance, in Funtuwa’s Sa’adatu Sa’ar Mata (“Sa’adatu the Lucky Woman”), when the main character is going through a rough spot in her relationship, her parents and grandparents suggest she buy a love potion. Although Sa’adatu doesn’t believe in such potions, she must find a way to compromise with prior generations, and, as Funtua explained in an interview, to reconcile the presence of this “age-old tradition” with newer knowledge. (Sa’adatu ends up swapping out the potion for milk, honey, meat and dates, and eventually lives happily ever after.)

The frankness of the wisdom on offer has rankled some critics, though, who blame foreign influence for what they see as nontraditional or anti-Islamic messages in the works. The early 2000s saw the formation of a the Kano State Censorship Board, along with several state-organized book burnings. In 2007, tensions came to a head when the state censors announced they would begin requiring writers to register individually with the board, and to seek line-by-line approval before releasing their works. The writers went on strike in protest, and the Association of Nigerian Authors had to broker a truce, says McCain.

Things remained tense until around 2011, but have cooled down since then, says McCain. Such showdowns remain common in academic settings, though, where littattafan soyayya is often taken less seriously than it deserves. As author Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, whose works are a common sight in secondary school classrooms, said an interview, “if I had that much soyayya in it, the education people [wouldn’t] put it in the syllabus.”

Because of this, translation of littattafan soyayya into other languages is often “a labor of love,” says McCain, who has undertaken some of it herself. As a result, English language readers who would like to learn more about the genre have a limited number of entry points (though one, an upcoming photography book called Diagram of the Heart, looks exciting). One good place to start is Sin is a Puppy (That Follows You Home), a twisty, acerbic tale of one relationship’s effect on a community by soyayya pioneer Balaraba Ramat Yakubu. Released by Indian publisher Blaft in 2012, Sin is a Puppy… is the first full-length contemporary Hausa work by a woman to be published in English, and is available on Amazon in both paperback and Kindle editions.

A few years before the translation, Yakubu was interviewed about her work. After expressing her desire to see her works in other languages, she brought the conversation back to her guiding principle: appealing to her current audience. “Whenever I write or talk, I side with women,” she said. “All I want is for women to get their rights. That’s what my books are about and what I stand for.”

Update, 2/2: This article has been updated to correct several chronology and translation mistakes. We regret these errors.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook