How One Photographer Finally Convinced a President to Give Him Full Access

The job was meant to be capturing official handshakes, but it turned into documenting history.

President Johnson meets with candidate Nixon. (Photo: Yoichi Okamoto/Public domain)

It might be said that official White House photography began with a very unofficial photograph of Eleanor Roosevelt.

As the story goes, Roosevelt was out riding her horse when she was spotted by Abbie Rowe, who was then working for the public roads bureau. According to some he was doing manual labor, a tough job for anyone, but particularly for Rowe, whose legs had been damaged by polio; other versions hold that he was already at work as a photographer, documenting the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Either way, when Rowe saw the First Lady, he took her picture, and she was charmed enough that they began a relationship.

Soon, Rowe was working as photographer for the National Park Service, and in 1941, he was given a new assignment. His job would be to photograph the president.

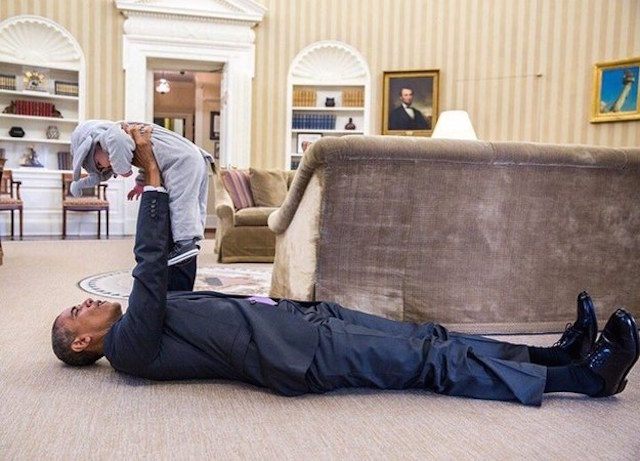

So many babies to make faces at, so little time. (Photo: Pete Souza/Public domain)

Today, it’s almost a given that the public will be given a glimpse inside the President’s world. Since 2009, we’ve seen President Obama at work and play, and the Obama kids goof around and grow up. There are pictures of the president making silly faces at so many babies, and a picture of the president and his staff watching, live, the assassination of Osama bin Laden.

Photographs like these can have a huge impact on the American public’s relationship with our president: the photographs can “affect the image and memory of their term and how the public perceives the president,” says Michael Martinez, an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, who’s studying presidential photography.

But the tradition of hiring an official photographer, with virtually unlimited access to the President and his family, snuck into the White House. Go looking for the first “official” White House photographer, and you’ll find more than one.

Abbie Rowe was still working for the White House when JFK took office. (Photo: Abbie Rowe/Public domain)

The first president ever to be photographed was John Quincy Adams, who sat for a daguerreotype in his 70s.The first president to sit for a photograph during his presidency was William Henry Harrison, who was photographed at his inauguration in 1841. But that photo’s been lost. The oldest surviving photograph of a sitting president, taken in 1849, is of James K. Polk.

But Rowe was the first photographer to regularly document a president’s activities. At first, his assignment had him covering President Roosevelt’s most official public work—ceremonies, major announcements, visits from foreign ambassadors and leaders. At the time, the White House press corps, was strongly, sometimes forcibly discouraged from taking photos of the president in his wheelchair or getting in and out of cars, and Rowe’s official photos followed suit. It’s easy to imagine, though, that Rowe, who suffered a more mild disability from polio, would be sympathetic to the president’s desire to emphasize his strength rather than focus on his weaknesses. After a few years, Rowe did start to get a closer view of the president, too. His photos still covered the “pomp and symbolism” of the president’s work, but the situations were more intimate meetings, with kids or artists or recently pardoned turkeys.

It was John F. Kennedy, though, who first saw the potential for a photographer to tell a story and to reveal the interior life of a presidency. Kennedy had a harem of photographers. Jacques Lowe documented Kennedy’s campaign and continued to follow the president during his first years in the White House. Stanley Tretick, who took the famous picture of JFK, Jr., under the president’s desk, never worked directly for JFK, but the president promised him regular exclusive access. By that point, government photographers, usually from the military, were also regularly assigned to do the job Rowe had pioneered, documenting official events.

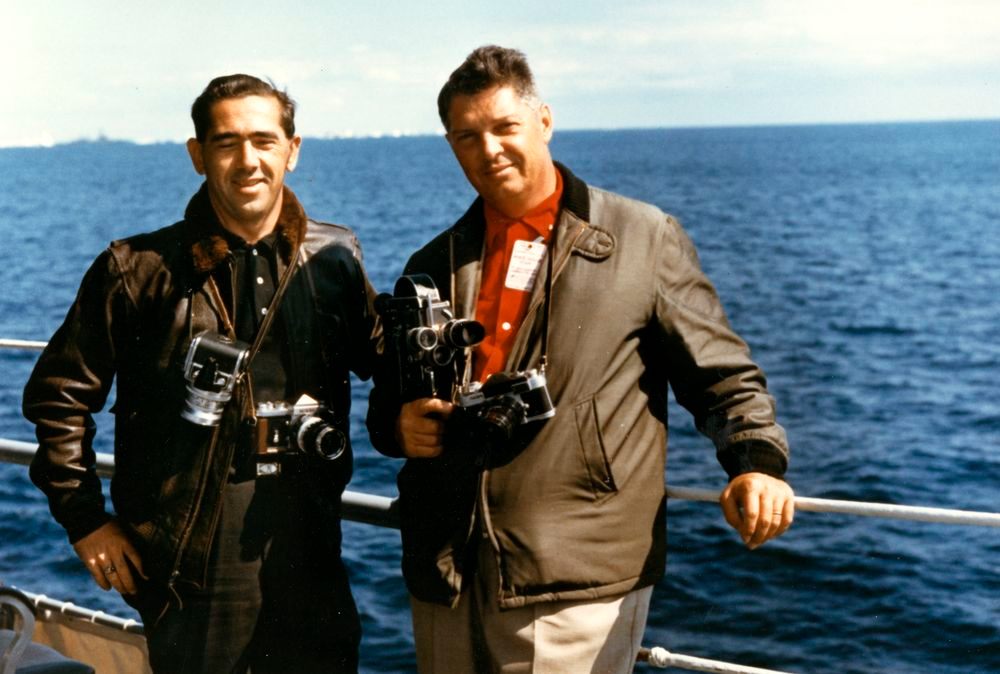

Cecil Stoughton (right), and Robert Knudsen, another White House photographer. (Photo: Robert Knudsen/Public domain)

Among all Kennedy’s photographers, though, one, Cecil Stoughton, is often called the “first official White House photographer.” Stoughton worked for the Army’s Public Information Office and after covering Kennedy’s inauguration, he was assigned to the White House full time. A large part of his job, along with other staff photographers, was to document official events: he’d sit waiting for a buzz from the President’s secretary before rushing to the Oval Office to take a couple of pictures. But he also developed a close enough relationship with the First Family that he’d be allowed to take photographs of more intimate moments and travel with them. He started taking home videos of the family on vacation.

One particular set of photos cemented Stoughton’s place in history, though. He was traveling with the president on Nov. 22, 1963, the day JFK was assassinated. After the president had been shot, when Stoughton heard the vice president was getting on a plane back to Washington, he got on it, too. The result: that series of iconic photos of Lyndon Johnson being sworn into office.

That was the one of the first iconic moments in which a White House photographer served as a documentarian of global news, that would have otherwise been dark to the public forever. Stoughton knew it, too. In Esquire’s account of the day, he tells Johnson’s people, “This is a history-making moment, and while it seems tasteless, I am here to make a picture if he cares to have it. And I think we should have it.” There’s so little room in the space he has to ask Johnson, Lady Bird, and Jackie Kennedy to back up. Jackie’s blood-stained skirt is cut out of the frame.

The famous photo of Johnson’s swearing in. (Photo: Cecil Stoughton/Public domain)

After that, the job changed. In the Johnson administration, the president hired a photographer directly for the first time, and that photographer argued for unrestricted access—enough leeway that he could frame the story himself.

Johnson had met Yoichi Okamoto as vice president. The photographer had been working for USAID and had documented a few of the vice president’s trips abroad. Johnson had seen how the photographs of the Kennedy family had helped create an aura around the president; he wanted a photographer, too. He proposed that Okamoto join the White House as his official photographer, working for the president.

Before Okamoto agreed, he made a proposal of his own: He didn’t just want to photograph Johnson when Johnson wanted to be photographed. He wanted more unfettered access—to be able to document presidential history as it was being made.

Okamoto had more availability with Johnson than any photographer had ever had to a president before. He could walk into the Oval Office without being announced. He spent as many hours as he could at the White House. “You just have to be there all the time,” he told one of his successors. “You can’t not be there.”

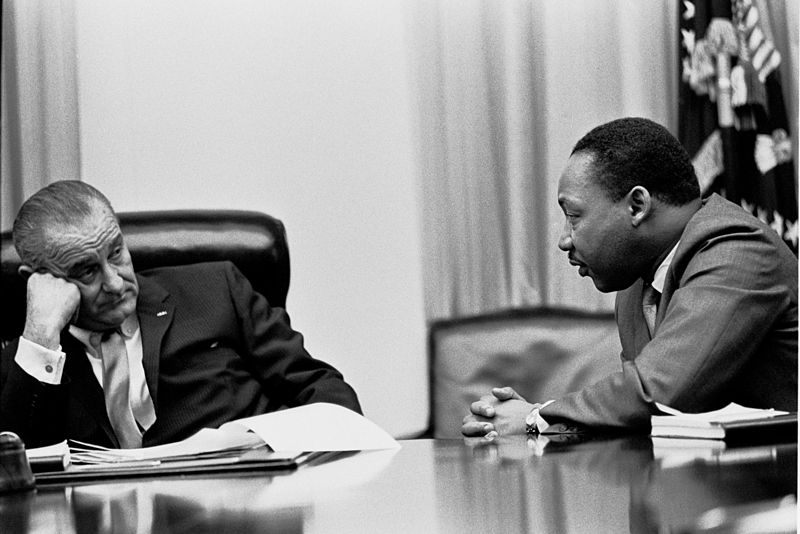

LBJ meets with MLK. (Photo: Yoichi Okamoto/Public domain)

Because he was there all the time and because he didn’t have to wait for Johnson to call him to work, Okamoto photographed his president holding meetings from his bed in the morning, arguing with aides, laughing, scoffing, shaking hands with throngs of voters, meeting with Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Richard Nixon, getting his hair cut, in the hospital during and after surgery, swimming in the White House pool, petting his dog.

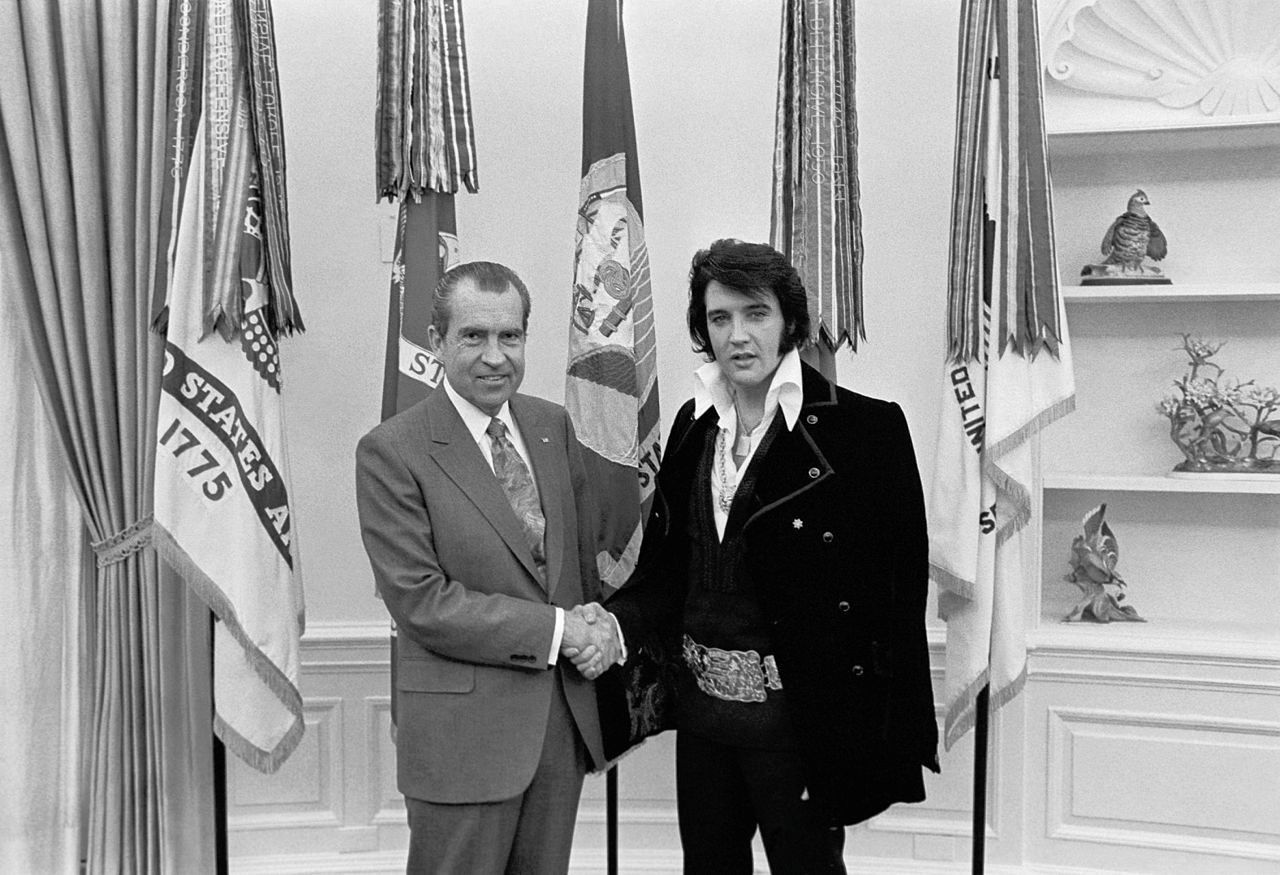

Not every White House photographer after Okamoto enjoyed the same amount of freedom. Nixon kept his photographer, Ollie Atkins, at arm’s length, and the photos that came from the White House, up until Nixon’s resignation, returned to the hand-clasp, meet-and-greet style of the past. (The famous picture of Nixon and Elvis shaking hands is typical of this.) The Clintons also preferred to keep some of their privacy. Jimmy Carter didn’t have a personal photographer at all; he offered the job to Tretick, who’d photographed JFK, but the photographer turned him down. “’I didn’t feel he wanted an intimate, personal photographer around him,” he told the New York Times.

Nixon meets Elvis. (Photo: Ollie Atkins/Public domain)

But some presidents—Ford, Reagan, both Bushes, and now Obama—let their photographers into the day-to-day life of the president. It’s a job that’s intimately connected, especially now that digital images can be distributed so quickly, with the public relations aspect of the presidency, the shaping of a positive image of the president. But it also has to succeed on its own terms. ”To be able to see the people in real moments, to see their human side, I think is valuable,” says Martinez, the professor.

Photojournalists who cover the White House, though, worry that those “real moments”, when shot by a staff member, don’t tell the whole story. The Obama administration has provided the public with a steady-stream of feel-good pictures of the President while keeping White House doors closed to independent photographers, and in 2013, the White House Correspondents’ Association wrote, in a letter to the White House press office, that “officials in this administration are blocking the public from having an independent view of important functions of the executive branch of government.”

Social media has brought visual messaging to whole new levels during Obama’s presidency, as well. While some White House reporters have groused about their lack of access—the current president has conducted 274 q-and-a sessions with press corps as of August, compared to George W. Bush’s 581—Obama has given a record number of interviews. Many of the accompanying images come directly from Pete Souza’s camera, as it’s incredibly convenient to download a free, high-quality photo in the public domain.

Regardless, there can be something special that comes out of a long term, day-to-day relationship between a photographer and his subject. Okamoto was the master of this. “Nobody had done it that way before, and pretty much nobody’s done it since,” President Ford’s photographer, David Hume Kennerly, said in a Times interview. It’s still the standard to aim for—to capture those moments of tension, grandeur, and mundanity that make the president seem both powerful and real.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook