How the Nazi Salute Became the World’s Most Offensive Gesture

Hitler invented German roots for the greeting—but its history was already filled with fraud.

The Olympic Salute, Gra Rueb, c. 1928 (Photo: Vincent Steenberg/CC BY-SA-3.0).

Recently, a certain politician’s practice of asking his supporters to recite a “pledge to vote” at his campaign rallies has led to rampant, politicized speculation that the “pledge” has some sort of ulterior significance.

maybe she accidentally glued her fingers together and was just trying to point pic.twitter.com/erG5schu1C

— Olivia Nuzzi (@Olivianuzzi) March 12, 2016

Specifically, some are taking the Trump campaign’s combination of inflammatory, racism-tinged statements and nefarious supporters as reason to compare the pledge salute to the infamous Nazi salute mandated throughout Germany during Hitler’s time in power. Its association with one of the most horrific regimes in world history has overwhelmed any other context for the gesture in our collective memory.

But historically, similar salutes have been used for entirely different reasons, and even Hitler acknowledged he was not the first to institute it.

In the 20th century, the Nazi salute was used widely by fascist governments and groups, including the Italian Fascists and the Spanish Falangists. These extremist groups, and particularly the Italians, collectively advanced the idea that the salute originated in ancient Rome, according to Martin M. Winkler’s The Roman Salute: Cinema, History, and Ideology. However, Winkler’s exhaustive research into ancient Roman accounts and depictions of military salutes unearths no evidence that the so-called “Roman salute” ever existed.

The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David, 1784 (Public Domain).

In fact, Winkler traces the salute to more recent artistic depictions of ancient Romans, beginning with Jacques-Louis David’s 1784 painting, The Oath of the Horatii. According to Winkler, the painting, which depicts three brothers saluting their father and pledging to protect Rome, “provided the starting point for an arresting gesture that progressed from oath-taking to what will become known as the Roman salute.” Other neoclassical artists began to depict similar poses, and the myth was perpetuated through the early 20th century as it spread throughout depictions of ancient Roman society, including an early 20th century stage production of Ben-Hur. The myth was so widespread that it is believed to be behind the adoption of the official Olympic salute, which stopped being used after the rise of Nazism.

The Italian Fascists promised that their government would restore Italy to the glories of ancient Rome, so advancing the myth of the Roman salute was certainly in their interest. It’s odd, then, that Hitler would choose to adopt a salute that had such distinctly non-German associations. But Hitler contrived a distinctly German “take” on the salute, recorded in Hitler’s Table Talk (January 3, 1942):

I made it the salute of the Party long after the Duce had adopted it. I’d read the description of the sitting of the Diet of Worms, in the course of which Luther was greeted with the German salute. It was to show him that he was not being confronted with arms, but with peaceful intentions. In the days of Frederick the Great, people still saluted with their hats, with pompous gestures. In the Middle Ages the serfs humbly doffed their bonnets, whilst the noblemen gave the German salute. It was in the Ratskeller at Bremen, about the year 1921, that I first saw this style of salute. It must be regarded as a survival of an ancient custom, which originally signified: “See, I have no weapon in my hand!”

Essentially, Hitler fabricated a Germanic history to the salute to circumvent accusations that his regime had adopted a non-German custom. There is no historical evidence regarding the use of a “German salute” to greet Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms—but Luther’s supporters did hope that his appearance at the diet would help loosen Rome’s political power over Germany at the time. It’s possible Hitler chose his fabrication to subtly undermine the idea that the salute was Roman in heritage.

Regardless of the origin story used, fascists groups consistently manipulated a false history to imply that they would return their nations to mythologized “golden years.”

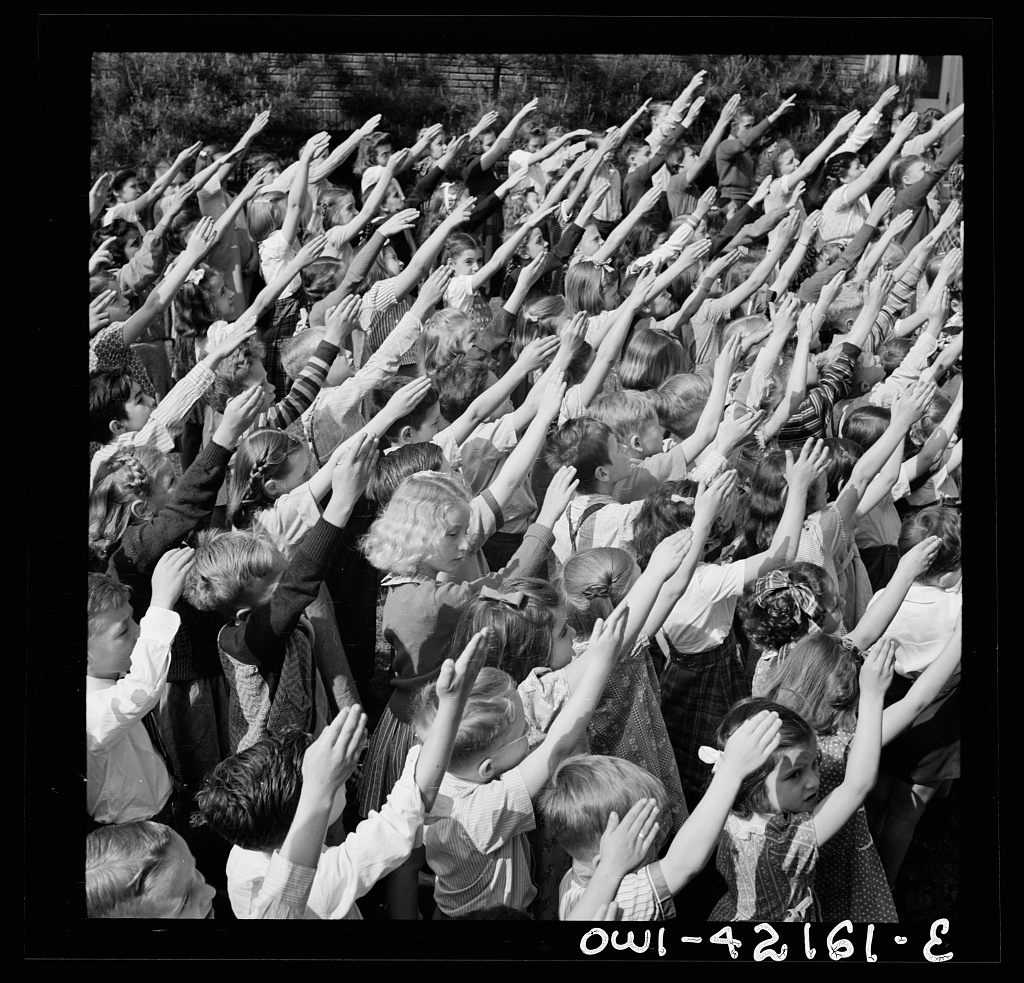

Southington, Connecticut. School children pledging their allegiance to the flag in May, 1942 (Photo: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection/LC-DIG-fsa-8d35173).

While the “Roman salute” was entirely invented, one salute existed prior to the rise of fascism that was very similar to the Nazi salute. Its origins? Entirely American. As CNN explained in 2013, the Pledge of Allegiance was written in 1892, as part of a campaign to bring American flags—and an increased sense of patriotism to a country still recovering from civil war—to classrooms around the country. The effort was spearheaded by Daniel Sharp Ford, owner of Youth’s Companion magazine, who asked Francis J. Bellamy to compose a Pledge of Allegiance. The pledge was a widespread hit, but Ford still felt something was missing. So, Youth’s Companion instructed pledge reciters to perform a salute, which CNN describes:

The Bellamy Salute consisted of each person—man, woman or child—extending his or her right arm straight forward, angling slightly upward, fingers pointing directly ahead.

With their right arms aiming stiffly toward the flag, they recited: “I pledge allegiance…”

For decades, the Bellamy salute was entirely uncontroversial. But by the mid-1930s, comments on the salute’s similarity to Nazi and other fascist salutes began emerging. According to CNN, a particular concern was that fascist propagandists could crop the American flag out of pictures of U.S. citizens reciting the pledge, thus manipulating the images to imply American support for the Nazis or other fascists.

Therefore, Congress passed an amended Flag Code on December 22, 1942, decreeing that the Pledge of Allegiance “be rendered by standing with the right hand over the heart.” The unfortunate association was severed, and the Bellamy salute quickly faded from memory. The salute’s fraudulent history has been largely forgotten but its symbolic potency remains.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook