How the Women-Led ‘Bread Boycotts’ Changed 20th Century Food Pricing

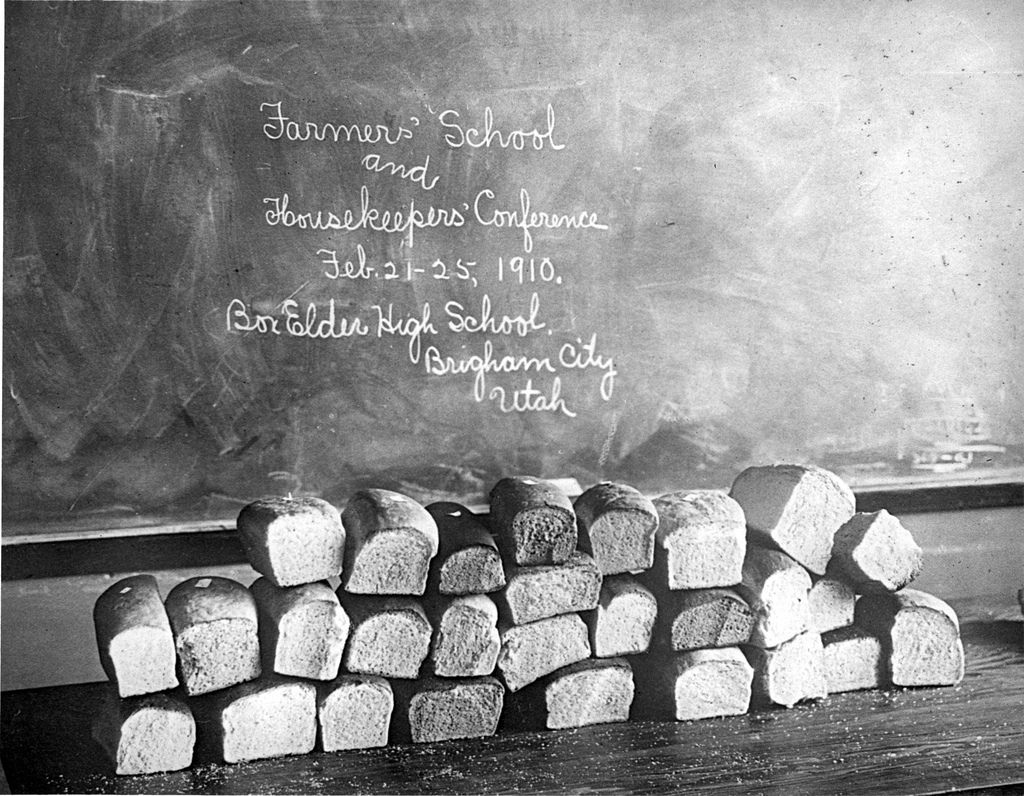

Leaves of bread piled up for a contest in 1910. Five years later, Chicago’s Clean Food Club called upon housewives to bake their own bread to protest rising prices. (Photo: Cornell University Library/flickr)

It all started in October 1966 when Mrs. Paul West (as she was identified by news outlets) complained to a Denver grocer that the price on a jar of olives had gone up four times in a month.

The grocer told her to “stick to your cooking and let us decide prices,” according to West, who recounted the incident for a LIFE magazine profile that labeled her a feisty provocateur.

A slip of a woman with an orderly poof of snow white hair, swooping cat eye glasses and dramatic eyebrows, the 52-year-old West promptly organized a boycott of five supermarket chains on behalf of her group, Housewives for Lower Food Prices. Within a week the boycott had swept across the nation and beyond, crossing the border to Canada. Food prices were rising everywhere, and people—especially the women who did the bulk of shopping for their households—were sick of it. West (who said she found picketing to be “unladylike”) said, “I’m not an organizer, I’m simply a housewife disgusted with food prices.”

West, though dogged, was no first. Although seldom recalled as a protest movement, women across the nation had been bringing food sellers to their knees for decades, especially bakers. Disenfranchised in any number of ways, the female capacity to buoy or bomb the markets was real. It was a power that they were only too happy to wield.

The Housewives League in action for WW1 food aid, New York. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In 1915, the housewives of Chicago balked when the Master Bakers’ Association announced their plans to raise bread prices. The Clean Food Club exhorted its membership to bake their own bread out of rye, corn and even potatoes. In 1921, organized New York City housewives didn’t even care if the price was low—they agitated for a better quality of bread. Their demands for a standardized loaf reached official ears, and the Deputy Commissioner of Markets, Louis Reed Weizmiller, convened a congress at City Hall to discuss a proposed boycott. Weizmiller didn’t doubt the women would get what they wanted.

“Mrs. Weizmiller contends that the housewives are in control of the situation,” wrote the New York Times. “If they want a standardized loaf, Mrs. Weizmiller said, they will be able to command it.”

In 1923, the Bread Committee of the Baltimore Housewives League called for a boycott of bakers that had ratcheted bread prices up to two or three times higher than usual. Three years later the Baltimore group were after the “bread gougers” again, trying to organize at least 1,000 women to march on the White House to reduce the cost of bread loaves by a cent. The organization’s president perhaps overstated the restorative power of toast when she told the New York Times, “Every day one reads of gifts made to carry on the work in children’s hospitals. We are doing a better work than this. We are trying to get the price of bread down so all children may have plenty of it and be so well nourished and healthy they will not need hospital cure.”

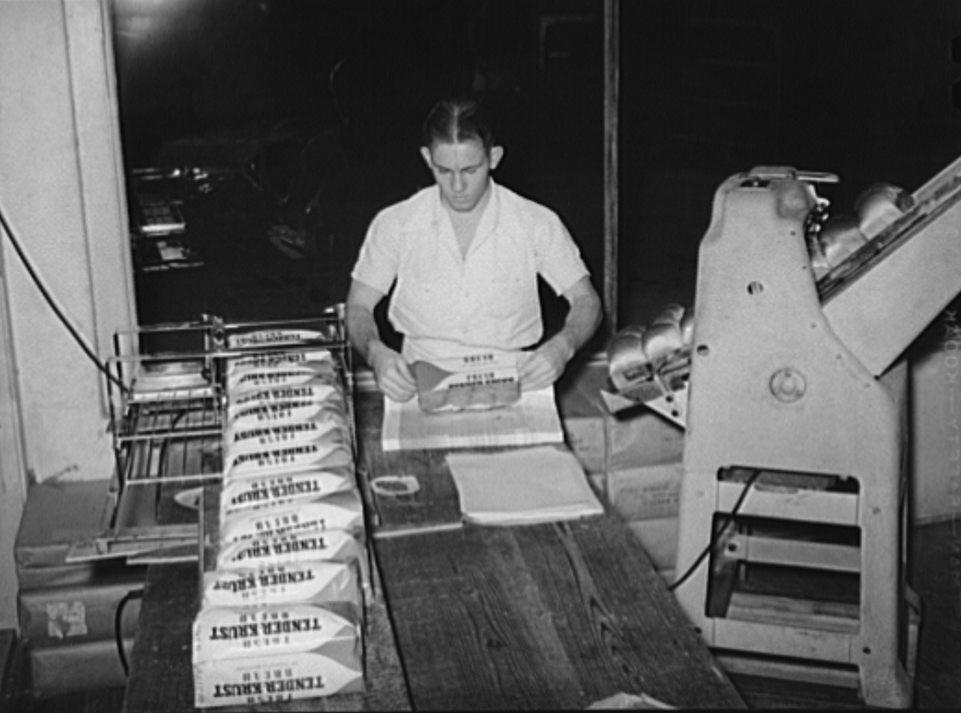

Wrapping sliced bread in San Antonio, Texas, in 1939. There was a short-lived ban on sliced bread during World War Two. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In 1943 it was an official effort to keep bread prices down that set off an uproar. In a wartime conservation and cost control measure, the government banned sliced bread, which was wrapped in a heavier weight paper than unmolested loaves. Both housewives and bakers balked; the unsliced bread was inconvenient and bakeries who owned their own slicing machines were allowed to continue selling sliced bread, putting others at a disadvantage.

The ban lasted about two months before being revoked. Although the pressure applied by housewives undoubtedly played a role, the government did not officially acknowledge this and newspapers snickered at their efforts. “Sliced Bread Put Back on Sale; Housewives’ Thumbs Safe Again,” read the Associated Press headline on March 8. The ban was particularly unpopular with “those housewives who were unable to find a good bread knife to buy,” the article continued.

Media jabs did not scare housewives away from wielding their economic power; in 1950 they successfully scuttled spiraling bread prices in Tennessee after four bakeries raised their prices. Stores stopped stocking their bread after women refused to buy it, and a baker in nearby Murfreesboro stepped in to supply cheaper goods.

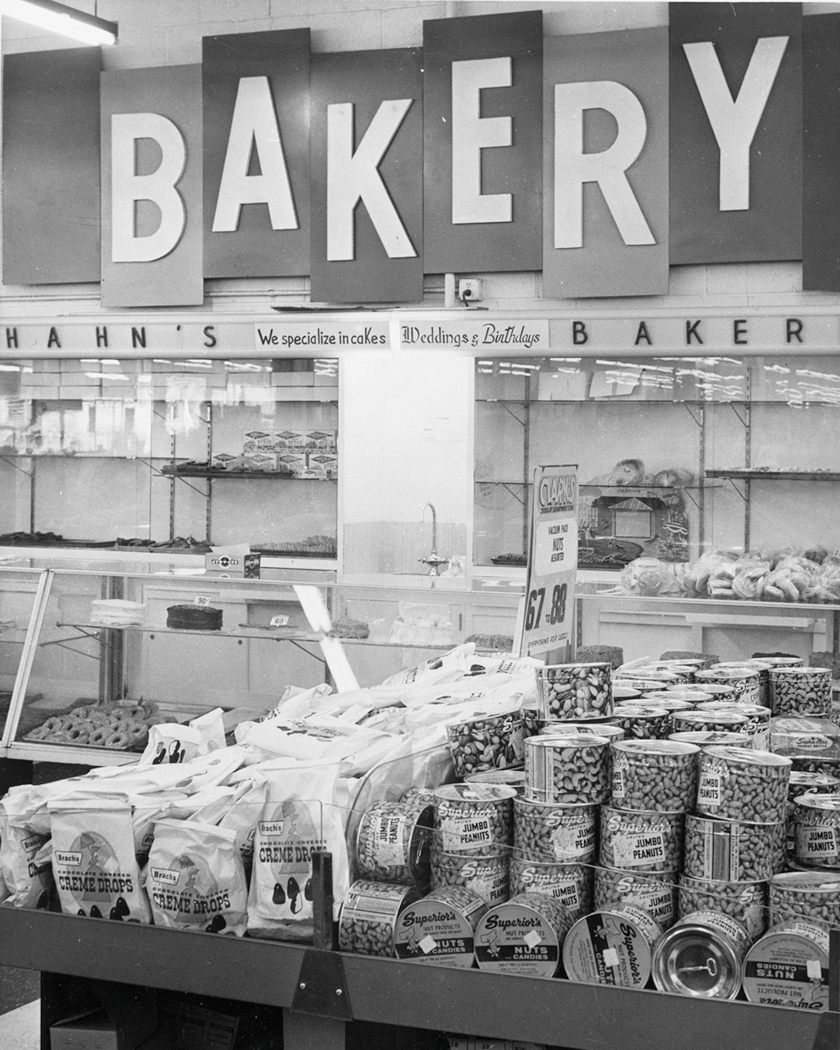

A bakery counter at Clark’s, North Carolina, c. 1963. (Photo: State Archives of North Carolina)

Whether West of the 1966 Denver-based boycott knew of these historic efforts to keep prices down is unknown, but it seems likely she would have heard of a successful bread boycott in Phoenix, Arizona that took place earlier the same year.

Like her predecessors, West garnered sneers. The New York Times called the protest a “ladycott”. One grocery executive (who seemed to have forgotten who buttered his bread) told LIFE, “The housewives are emotional. The logic of our balance sheet does not interest them.” Another sniped that “Maybe they need a recipe instead of a picket line.”

A Minnesota bakery, c. 1975. (Photo: US National Archives/flickr)

Critics claimed that the price climbs were inevitable and any reductions would be momentary; but The Federal Trade Commission agreed that West and her cohorts were right; at least when it came to bread and milk, supermarkets were overcharging to increase their profits. Two supermarkets lowered their prices the very first day of the boycott; the rest quickly followed suit. For decades, grocers had been attempting to swat away the concerns of customers because they were women; again they failed.

A spokesman for another outlet had a better grip on the situation: “Let’s face it, the housewife has a veto power over the whole food industry.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook