How the World Became A Giant Ant Colony

Argentine ants on the move in California. (Photo: Mark Moffett/Adventures Among Ants)

Blasting out from their little corner of the world, they colonized continents, subdued native populations, and controlled territories stretching for hundreds of miles. Pathologically devoted to their queens, these determined explorers let nothing stand in the way of their dogged desire to conquer the world.

No, we are not talking about the Roman legionnaires, British Redcoats, or even Napoleon’s Revolutionary Army. The world is being taken over by Argentine ants, and humans are to blame.

On the surface, there is nothing particularly remarkable about the Linepithema humile, or Argentine ant. These tiny, carnivorous insects originated in the subtropical borderlands between northern Argentina, southern Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Individually inept due to their small size (when compared with other worker ants who can be orders of magnitude larger, and much more effective fighters), the Argentine ants function best within a group.

During the 16th and 17th centuries Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores made inroads into the jungles of Brazil and Argentina searching for El Dorado. On their return trips home, often enduring months of hardship and harrowing storms at sea, they were hailed as heroes. They were also unwitting vectors for some surprisingly capable guests.

Deep in the jungles, the damp 16th-century gear of our intrepid explorers proved fertile ground for ants to establish miniature colonies. The colonies continued aboard the creaky wooden ships–amazingly rationing their resources to survive months at sea for the return trip home. As shipping traffic to the New World intensified, so did the mass migration of ants. By 1850, a fully functioning Argentine ant colony had been established on the Madeira Archipelago, one of Portugal’s busiest trading hubs in the Atlantic.

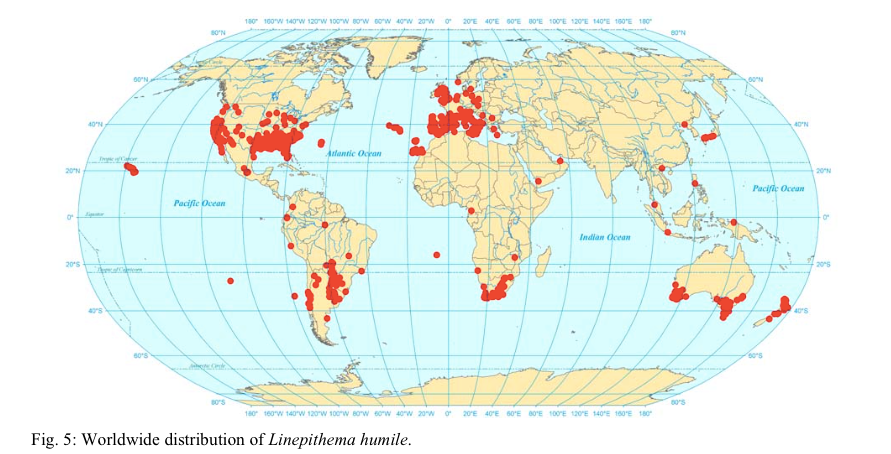

From the islands of Madeira, Argentine ants hitched rides wherever humans happened to be traveling. Japan, California, Australia, and the Mediterranean coast of Europe are now all hosts to invasive populations.

From their native range in Argentina, the L. Humile has spread across the world. (Map: Andy Suarez/”Worldwide Spread of Argentine Ant”/Myrmecological News)

In their native range, Argentine ants maintain relatively small, genetically distinct colonies that come into frequent contact with each other. Constant warfare is the status quo both between adjacent colonies, and with other ant species vying for control of territory and resources. This strife serves to check population levels, and prevents any single colony from spreading out of control–crucial for maintaining genetic diversity.

In the Argentine ants’ introduced populations, this intra-species infighting doesn’t exist at all. And this lack of conflict among the far-flung colonies is due, amazingly, to the way the ants smell.

According to Dr. Mark Moffett, an entomologist from the Smithsonian Institution, and one of the world’s foremost experts on ants, individuals from a particular colony recognize and communicate with each other based on chemical scents imprinted onto their bodies. In a Scientific American article from December 2011, he writes: “Ants, too, recognize one another by means of chemical cues [hydrocarbons] on their body surface, and they attack or avoid foreigners with a different scent. Ants wear this scent like a national flag tattooed on their bodies.” This “national flag”–a permanent birthmark—is what separates ant colonies from one another, and maintains order in their native Argentina. Within introduced populations, however, it is this same system of recognition that goes haywire, and allows colonies to reach magnificent sizes.

The humble Argentine ant worker. Individually tiny, massive as a colony. (Photo: April Noble/Ant Web)

Introduced populations of Argentine ants commonly share the same scent, and will act peacefully towards each other. This happens due to a process called genetic drift, writes evolutionary biologist David Queller in a June 2000 Nature article. In the smaller introduced populations, gene variability is reduced. This creates a genetic bottleneck, where all the ants in the introduced population are born with more homogeneous genes. The Argentine ants’ genes imprint the scent on their bodies through which they differentiate each other. When millions of ants are born with the same scent, they are tricked into thinking that they are kin, and will even attend to each other’s queens as if they were their own.

Genetic drift has given rise to the notion of “super-colonies” of Argentine ants: Billions of queens and workers actually making up what amounts to a singular colony spread out and disjointed over a huge area of land. In a series of experiments conducted at the University of Tokyo, Argentine ants born miles apart recognized each other as part of the same colony. Though they were born to different queens, and would never interact under natural circumstances, they had enough scent-similarities to act as friends. Yet, Argentine ants from outside of the super-colony were always met with violence. As always with ants, violent interactions demarcate the boundaries of territories.

We aren’t discussing minor introduced populations here—what we are seeing is a tidal wave of L. humile super-colonies wiping out native species. In California alone, Argentine ants have claimed over 500 miles of coastline. In Europe, these ants have expanded their territory almost 4,000 miles across the Mediterranean Coast. And, according to the University of Tokyo, these huge ranges function as singular super-colonies, larger than a significant portion of the member states of the United Nations.

How big can this worlwide ant colony get? In their native lands, colony size is limited by aggressive neighbors. In introduced populations, there are no L. humile neighbors to speak of, so the colonies can keep growing and reproducing queens and workers with the same “national flag” scent. Because Argentine ant queens stay with their original colony, introduced populations can expand indefinitely without the limitations imposed by neighboring colonies.

L. Humile closeup. (Photo: April Noble/Ant Web)

Reached by phone, Dr. Andy Suarez, an entomologist at the University of Illinois, said that this process of Argentine ant migration is only accelerating. He explained that a few hundred years ago, it took the ants months of traveling—not to mention the careful maintenance of resources—by ship to reach new continents. Now, in the modern era of hyper-connectivity and air travel, Dr. Suarez says, “Within 48 hours, all two places in the world are connected.”

With humans as their primary vectors, the speed at which Argentine ants can migrate to exotic new locales is unprecedented.

So how did a seemingly innocuous species of ant native to a tiny corner of South America become poised for world domination? According to Dr. Moffett, the answer lies, strangely enough, in the mathematics of the World War I. An English engineer named Frederick Lanchester deduced that, if many fights occur simultaneously in one area, the side with the greater numbers would always prevail regardless of the individual fighting power of the troops. The Argentine ants follow this law to a T. Because of their similar scents, and resultant ability to form super-colonies, introduced populations of Argentine ants are able to wield massive labor forces. Any native species are simply outnumbered and overwhelmed, ceding control of territory easily to the invaders.

There is one thing that could halt these monsters from taking over the world completely—climate change. Dr. Suarez has mixed opinions about the future viability of invading Argentine ants as lower genetic diversity equates to less adaptability for changing and difficult conditions. While climactic conditions currently favor the spread of L. humile super-colonies in the Mediterranean and California, the next few hundred years may prove to be the ultimate test, giving the native populations a chance to rise again.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook