How to Decode the Hidden Secrets of Havana’s Streets

Hand signals, street signs, color-coded uniforms, and more.

As a visitor to Havana, Cuba, it’s easy to feel like you’re missing something. Since the revolution in 1959, Cubans have found ways to get what they want, even if buying a house once meant getting a sham marriage to the previous owner or eating well meant buying food on the black market. For every official system, it can seem like there’s another, less official way of getting by, working just out of sight.

But some of Havana’s secrets are easier to decipher. Most places have codes, and as a visitor it can feel like they’re secrets to be unlocked. Here’s a quick key that’ll help decode some of the basics.

There are two official currencies.

Cuba has two currencies, the Cuban peso, or CUP, and the convertible peso, or CUC. Most Cubans get their salaries in CUP; foreigners uses CUCs. The bills are the same size, but there’s an easy way to tell them apart. CUP feature the faces of national heroes; CUCs feature monuments.

There’s a symbolic connection between CUPs and CUCs, though: the same denomination will honor the same hero in both currencies. So, for example, a 5 CUP bill has a bust of Antonio Maceo, second-in-command during the Cuban revolution, and the 5 CUC bill shows the Havana monument built in his honor.

No one calls Avenida Salvador Allende by its official name.

Originally, this street, the first connecting old Havana to the stately Vedado neighborhood, was named after the Spanish king Charles III—and among locals, it’s still known by its old name, Avenida de Carlos III.

Before you can hail a collective taxi, you have to know where you’re going.

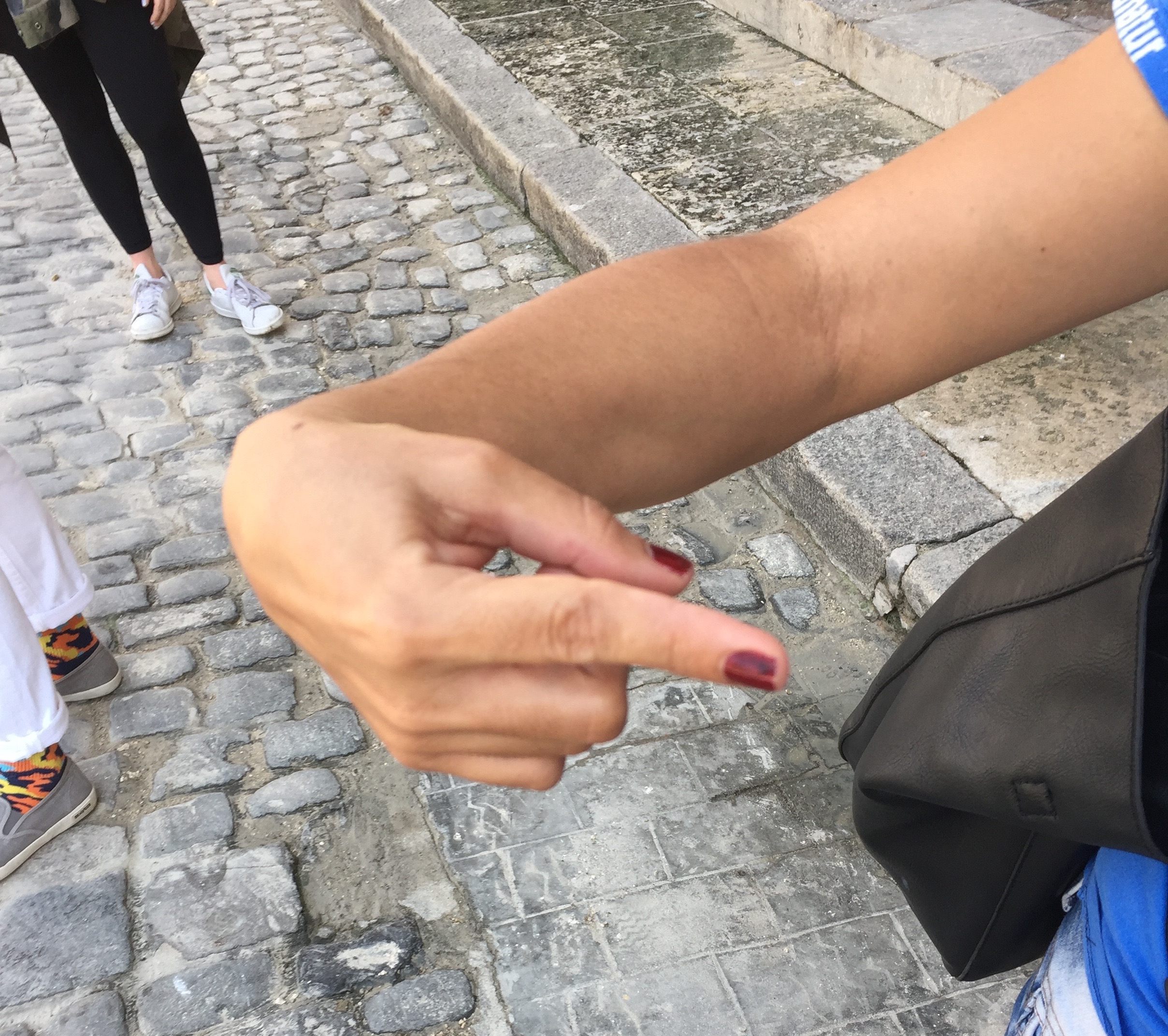

To avoid the overcrowded buses, many people use “taxis collectivos”—old cars that run regular routes along the city’s major thoroughfares. Not all the taxis on a particular street are going the same way, though, and they will only stop to pick up passengers that are going in the same direction the driver’s headed. Riders can indicate which route they want with hand signals. For instance, if you’re on the east side of Avinida Rancho Boyeres, you can signal that you’re headed to Vedado…

…Old Havana…

….Carlos III…

…or straight ahead.

Many of the cars belong to the government.

All-gray license plates with numbers starting with P are privately owned. A blue strip on the left-hand side of the license plate indicates it’s a government car—and more likely to be made after 1959 and imported from China.

Since 2014, the government has been selling imported cars, but at an incredible mark-up. Before that, the only way for a private person to buy a car was to get a letter of permission from the government, which, on the secondary, underground market, were worth about $2,000.

Uniforms are color-coded.

Elementary school kids wear red shorts; middle school students wear mustard-brown pants and skirts; pre-college students wear dark blue bottoms and light blue tops. If you see groups of young people wearing sharp white shirts and black bottoms, they’re likely studying to go into the tourism industry.

Teenagers also color-code themselves.

Havana teenagers who are passionate about pop identify as mikis (after Mickey Mouse), and girls in this group often wear tight, bright pink outfits or dye their hair the same shade. Emo kids wear black, as do friki teengagers, who spike their hair and wear tattoos.

A cute little park can mean a building didn’t make it.

Many of Havana’s buildings are in bad shape, but even after the Office of the Historian of Havana designates a building for restoration, families can choose to stay or to move out. Often they stay, because there’s a real risk the renovated building will house fewer families and not all of the previous residents will be able to return. Because of these and other delays, some buildings can’t be saved, and after they’re torn down, the city will turn the empty lot into a pocket park.

If you see this sign on a house, you might be able to stay there.

Casas particulares are private homes that pay a fee to the government in order to operate as guest houses.

A white bust of a man’s head means you’re outside a school or other government building.

It’s Jose Marti, another hero of the Cuban Revolution. There’s also a giant statue of him in the Plaza de la Revolucíon.

The numbered stones low to the ground aren’t a secret code.

They’re street signs.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook