In Istanbul, You Can Find Old Prisons in Restaurants, Mosques, Even 4-Star Hotels

Scattered around the city are some of the most notorious jails, if you know where to look.

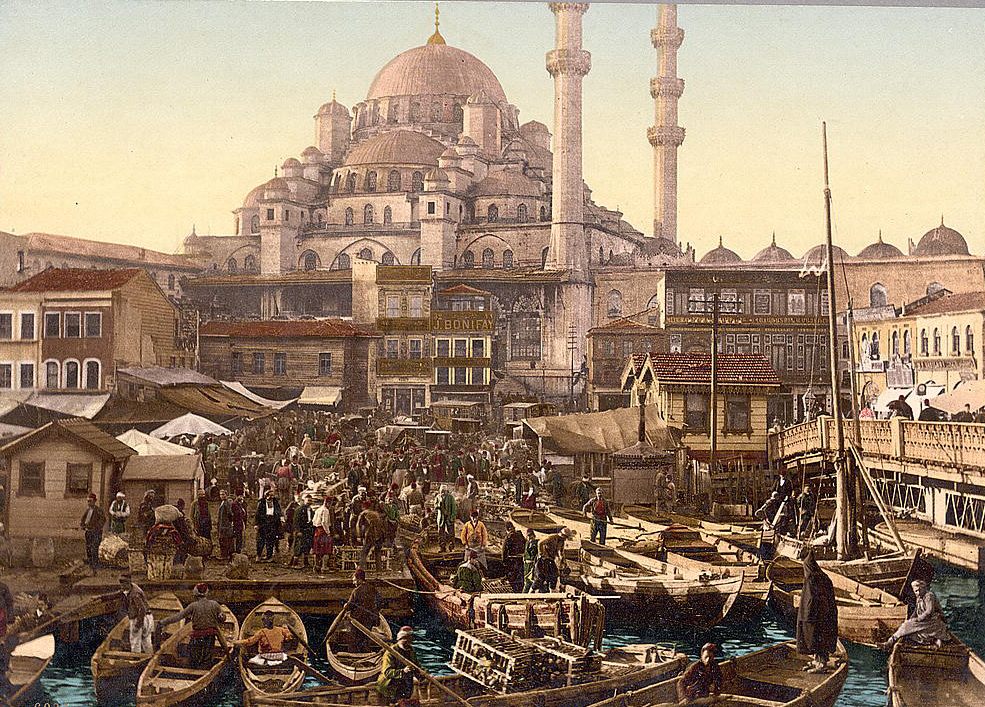

A photochrom of Istanbul, c. 1890. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-03047)

If we know anything about Turkish prisons, we probably learned it from the 1978 film Midnight Express, loosely based on Billy Hayes’ memoir of the same name. Hayes later apologized to Turkey for the unrealistic brutality of Turkish characters in the film.

The real story of Turkish prisons is as long and multi-layered as the country itself—starting with the Byzantines and taking on different forms through the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic. The Ottomans’ strong relations with European powers meant that there were even British and Russian prisons in Istanbul. This is also the city of reinvention, so expect to find prisons in the most unexpected places: a restaurant, a hotel, or a mosque. While other cities might hide their prisons away, Istanbul has adapted them to the pace of the megacity. But the eerie traces of the past remain like prisoners’ scratches on the walls.

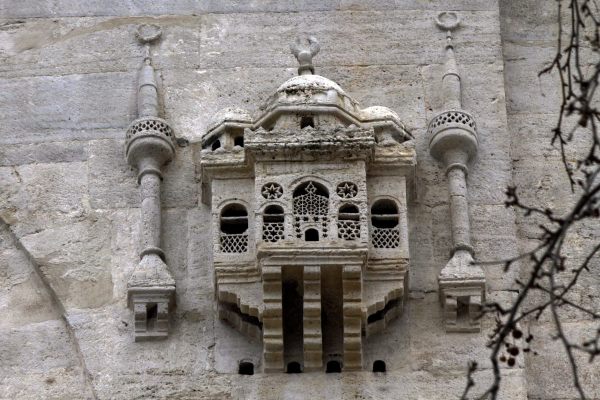

Inside the Yeralti Mosque, Istanbul. (Photo: Ggia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Yeraltı Camii (underground mosque) in Karaköy is one of the few subterranean places of worship in the Islamic world. But its earlier history is even more remarkable. The Byzantines built this space as the dungeon of Kastellion Tower, which held one end of the giant chain that stopped enemy fleets from entering the Golden Horn. Its conversion to a mosque is linked to the first Arab siege of Constantinople in 674-687. During the siege, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad called Süfyan bin Uyeyne was captured and died in the dungeon. Around 1,000 years later, a Sufi dervish saw Uyeyne’s grave in a dream, and one room of the mosque holds his tomb. Yeraltı Camii is one of the most popular places of worship in Istanbul during the month of Ramadan.

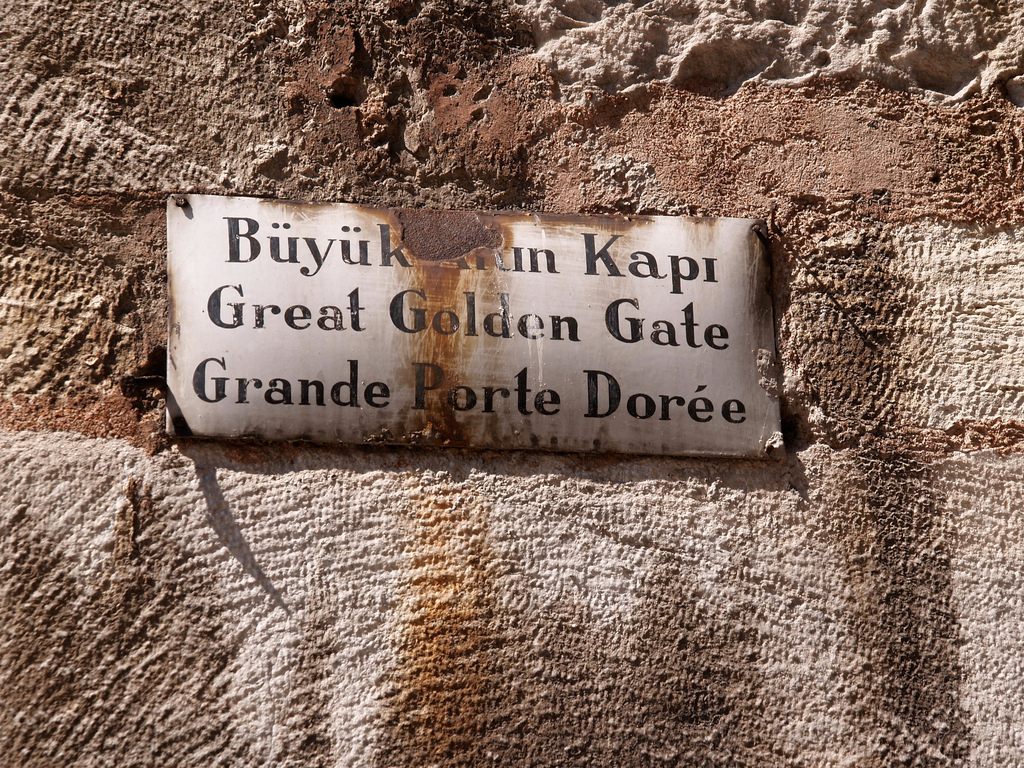

A sign for the Golden Gate. (Photo: Dave Proffer/CC BY 2.0)

When Emperor Theodosius expanded the city’s land walls to the west in the 4th century, he also ordered the construction of a processional entrance called the Golden Gate. At first the castle around the gate was used as a reception room for visiting kings and ambassadors. Later it became an infamous dungeon whose Turkish name is Yedikule, meaning “seven towers.”

In the Ottoman era this was the prison for foreign ambassadors who had offended the sultan. The novelist Leo Tolstoy’s ancestor Count Pyotr Tolstoy was imprisoned in the Yedikule dungeons for four years, returning to Russia in 1714.

A view of the Golden Gate, taken from outside the walls. (Photo: Greenshed/Public Domain)

But the more unsettling prisons are those that you can walk by without even noticing. To the west of the Galata Bridge in Eminönü is an innocuous-looking 19th-century building that holds jewelry shops and a restaurant on the top floor. Its former use is betrayed by the name Zindan Han, meaning “dungeon caravansary.” A section of the city walls used to run along this shore of the Golden Horn, and the tower attached to the 19th-century building was a Byzantine prison.

The Turkish name Baba Cafer Kulesi comes from a Muslim ambassador Baba Cafer who was imprisoned and died in the dungeon. Similar to the story of Süfyan bin Uyeyne and the underground mosque, Baba Cafer’s tomb became a pilgrimage site for Muslims. Despite this sacred heritage, the Ottomans continued to use the tower as a prison for women and debtors. These poor souls used to shout from the windows at passersby, begging for enough money to pay off their debts.

Yedikule Fortress, Istanbul. (Photo: TripMapGuide.com/CC BY 2.0)

On a quiet street close to the iconic Galata Tower is a restaurant called Galata Evi. Today it serves a mixture of Turkish, Georgian, and Russian dishes influenced by the Tatar co-owner Nadire Göktuğ. From the outside, there is little evidence that this building began life in 1904 as a British prison. The men and women confined here were guilty of civil crimes, and graffiti saying “three months” and “seven months” shows that most prisoners did not remain here long. With the occupation of Istanbul after World War I, Galata became a British-controlled zone and the prison was turned into a police station. The building was also a base for British spies working against the Turkish nationalist movement, and the headquarters of the British army force was located in the St. Pierre Apartment just across the street.

Galata Tower. (Photo: Harold Litwiler/CC BY 2.0)

The most unlikely spot for a former jail, though, might be the swanky Four Seasons in Sultanahmet, which used to be an Ottoman murderers’ prison. The impressive square-plan building with guard towers and a central courtyard was built around 1918. Orientalist touches such as patterned tiles around the windows and muqarnas-style corbels are features of the Neoclassical Turkish architecture that developed in the late Ottoman era. The original prison was closed in 1969 and then reopened in 1980 as a military prison. Famous leftists such as national poet Nazım Hikmet and novelist Orhan Kemal were held here, as Kemal recalls in his memoir “In Jail With Nazım Hikmet.” Socialist revolutionary Deniz Gezmiş was also held in Sultanahmet prison before his execution in 1972.

The Four Seasons Hotel in Sultanahmet. (Photo: Gryffindor/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Close to the iconic Sirkeci train station is a neoclassical building that looks little different from the surrounding hans and offices. But despite its plain appearance, there are many people alive today who shudder at the sight of this building. Sansaryan Han in Eminönü was built by Armenian architect Hosep Aznavour in the late 1800s. The owner Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan left the building to the Armenian Patriarchate, but in the 1930s ownership passed to the Istanbul Governorate.

From that time to the 1990s this was the Istanbul Police Headquarters, which was notorious for its torture of political detainees. The unfortunate Nazım Hikmet also spent some time here, as did humorist Aziz Nesin and folk musician Ruhi Su. Former inmates called Sansaryan Han “the coffin house” because its cells were shaped like upright coffins, not allowing the prisoners to lie down.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook