Exploring the Underground Railroad, in Brooklyn

A statue of Henry Ward Beecher by Gutzon Borglum in the garden of Plymouth Church. (Photo: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock.com)

A statue of Henry Ward Beecher by Gutzon Borglum in the garden of Plymouth Church. (Photo: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock.com)

Walking today through the tiny neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights, from the Manhattan views offered by the Promenade, past the rows of historic brownstones and tree-lined streets, you will find an old church tucked away on Orange Street. Organized in 1847, Plymouth Church is one of the oldest congregational churches in New York.

And, at one time, it was among the most controversial.

Designed in the style of a New England barn and decorated with stained glass from the workshops of J&R Lamb,and Louis Comfort Tiffany, it is hard to imagine that once this serene place of worship was at the fierce and volatile center of the fight to abolish slavery. What is even more remarkable is what lies hidden underneath it, one of the principal stops on the Underground Railroad.

The church’s ideological stance was established in its very beginning, when church leaders recruited the inspirational abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher to be their first preacher.

A photograph of Henry Ward Beecher c. 1875 (Photo: Falk 949 Broadway/Public Domain /Wiki Commons)

A photograph of Henry Ward Beecher c. 1875 (Photo: Falk 949 Broadway/Public Domain /Wiki Commons)

Already by 1848, Beecher was well on his way to becoming, as one biographer put it, “the most famous man in America.” Having preached in the midwest for 10 years, he carried the nontraditional look of a frontiersman. He wore his hair long, and his flamboyant oratory style was filled with slang and street talk. According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “the privilege of partaking of the spiritual food which Mr. Beecher so spicily serves up hedbominally for his congregation.”

From from the beginning of his ministry at Plymouth, he was a devoted abolitionist. “I will both shelter them (fugitive slaves), conceal them or speed their flight” Beecher promised, “and while under my shelter, or under my convoy, they shall be to me as my own flesh and blood.”

With his powerful theatrical oratory he was renowned as one of the pre-eminent speakers of his day. So much so that Lincoln invited him to deliver the address at Fort Sumter, saying, “We had better send Beecher down to deliver the address on the occasion of raising the flag because if it had not been for Beecher, there would have been no flag to raise.”

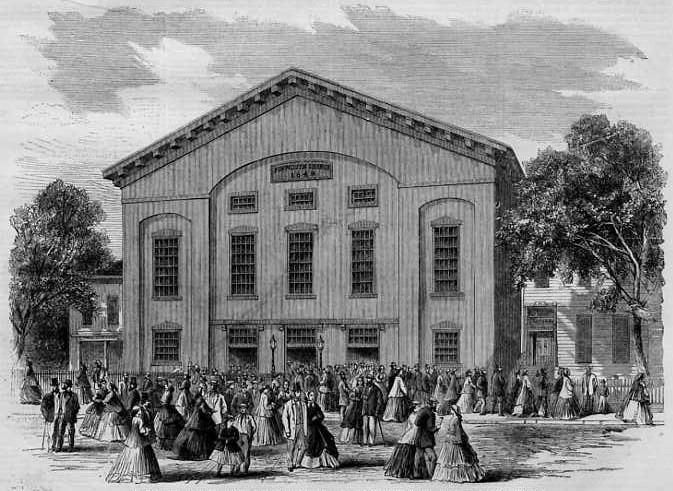

A wood engraving of Plymouth Church c. 1866 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The existence of this church, and what lies beneath its floor, have not gone totally unacknowledged. Devoted parishioner and long-serving member of the choir, Lois Rosebrooks has been serving as director of history ministry, giving tours by appointment as well as curating its own exhibit. We arranged to meet on a Monday afternoon, in a pew with a small silver plaque indicating that this is where Abraham Lincoln came to worship on February 26th, 1860. Such was Plymouth Church’s standing, that it remains the only church in New York which Lincoln attended.

Lincoln’s pew is marked with a silver plaque. (Photo: Plymouth Church/Flickr)

Lincoln’s pew is marked with a silver plaque. (Photo: Plymouth Church/Flickr)

Rosebrooks pointed out that while Beecher was the public figurehead, the fight against slavery enveloped the whole church. By its very definition, a congregationalist church was run by its own members. Not answerable to outside ecclesiastical supervision in the way say a Catholic church would be, it was the perfect independent group to lead the fight against slavery; prominent New York abolitionist Lewis Tappan freed the slaves held on the Amistad. Beecher’s sister, Harriet wrote one the 19th centuries best selling novel, the controversial anti-slavery book Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The first thing one notices about the Plymouth Church is its unorthodox interior. There’s no central aisle down which a bride would walk to the altar. Instead the church was designed, on purpose to resemble a theater: A stage juts out into the rows of curved seats.

Rosebrooks led the way behind the stage and a pipe organ that for many years was the largest in the United States. In the corner was a white door, and behind it, a narrow staircase underneath the church. Down the stairs, was a small ante-chamber with a bare earth floor and a heavy, cast iron door that at one point someone had written on in chalk “please keep closed.” The chamber led, in one direction to the opening to a tunnel.. In the other sat a large brick room, the air dry and cold, with dirt underfoot. A cavernous room, divided by old red brick archways, some charred from an old fire, the cavern led off into other, darker and more undisturbed chambers.

Plymouth Church interior. (Photo: Tony Fischer/Flickr)

Plymouth Church interior. (Photo: Tony Fischer/Flickr)

We were standing in one of most secretive places in America, hidden under the streets of Brooklyn Heights. This was one of the most important stops on the Underground Railroad, so much so it was known in hushed voices as “the Grand Central Depot’.”

This was the sanctuary underneath the church. With its low ceiling, it would have provided a perfect holding place. As Beecher claimed, “I opened Plymouth Church though you did not know it, to hide fugitives….I piloted them and sent them toward the North Star, which to them was the Star of Bethlehem.”

Returning to the antechamber at the foot of the staircase, a long narrow tunnel lined with wooden paneling gave off onto more smaller brick rooms, with the same archways and earth floors. In a 2007 New York Times article, Rosebrooks explains, “They were hidden in the church, we assume in the basement as that would the the safest place for them.”

Underneath Plymouth Church. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Underneath Plymouth Church. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The Underground Railroad is thought to have been responsible for the safe passage of as many as 100,000 slaves fleeing the South. Couched in secrecy and the railroad terminology of “stations”, “conductors” and “depots”, the Underground Railroad delivered escaping slaves through a clandestine system of sympathetic safe houses. With its proximity to the bustling docks of the East River only a few blocks away, the sanctuary crypts under Plymouth Church were ideally placed to be at the forefront of the Railroad.

Beecher’s involvement with the Underground Railroad started when he returned to his parish house located next door to the church to find a freed slave, Paul Edmondson crying distraught on his doorstep in 1848. Edmondson told Beecher of how his two young teenage daughters were being sold into slavery and headed for New Orleans as “fancy girls” He begged Beecher for help.

Slavery might have been outlawed in New York beginning in 1799 law (with all slaves legally freed by 1827) but the city was far from safe for free blacks. New York merchants and bankers dominated all aspects of the South’s cotton industry. Historian Frank Decker estimated that, “forty cents of every dollar paid for cotton ended up in the pockets of New York businessmen.” Organized gangs of slave catchers were dispatched from the South to track down and recapture escaped slaves. Their nefarious missions were authorized by Congress and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 that held that any found slaves “shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labour may be due.” The slave catchers didn’t confine their task to purely escaped slaves, but would often attack free blacks and sell them into slavery. It was amidst this treacherous atmosphere that the abolitionists of Plymouth Church went about their work.

Led by prominent underground railroad conductor Reverend Charles B. Ray, a group of abolitionists in New York had formed a “Committee of Vigilance” earlier in 1835 with the express mission of helping escaped slaves; “our first and practical business is to take charge of all escaping slaves......placing them where the slave pursuer can neither find nor molest them.” As Decker notes, “those seeking help knew how to locate people who would help.”

And the principal stop of the underground railroad was to be the hidden basement crypts of Plymouth Church.

In was in this atmosphere that Beecher accompanied Paul Edmondson to an abolitionist meeting held in the Broadway Tabernacle. What happened on the stage of the auditorium that night was as unorthodox as it was extraordinary; taking charge of the meeting Beecher held a slave auction for the two teenage girls, only a slave auction in reverse. Using his oratory talent and skill for the theatrical, Beecher pleaded with the audience for money with which to pay for the two girls. But rather than be sold into slavery, they were buying their freedom. Mocking actual slave auctions Beecher described the attributes of each girl. Patrolling the stage as though he were a boisterous slave auctioneer, he beseeched the crowd, “I would be ashamed if it were written down that such an assembly was gathered here......the poor pittance couldn’t be raised.” As the fervor inside the Broadway Tabernacle reached fever pitch, Beecher exhorted. “who bids? a thousand......fifteen hundred.....two thousand…twenty five hundred! Going, going, last call....gone!” And with that, Beecher and the generosity of the crowd saved Paul Edmondon’s daughters from a life of prostitution and slavery down in New Orleans.

A painting showing Henry Ward Beecher and Pinky. (Photo: Courtesy Plymouth Church)

Encouraged and inspired by the evening, Beecher brought his “mock slave auctions” to the congregation at Plymouth Church. From below the stage, the Grand Central Depot continued its secretive work delivering escaped slaves to safety while above ground, Beecher’s ministry grew and grew. In these days before the Brooklyn Bridge, so-called “Beecher boats” ferried thousands across the East River to hear him preach. He thundered across the stage stamping on the actual chains that had held John Brown. He conducted more and more slave auctions, persuading the congregation to buy freedom for slaves. The most famous auction occurred on February 5th, 1860, when Beecher and his congregation bought the freedom of a 9-year old slave girl from Washington DC, Sally Maria Diggs. Nicknamed Pinky, Beecher called her to the stage, telling the gathered congregation that she was due to be sold to the South for $900. As Beecher conducted his rousing mock auction the collection plate was passed around until over $1,100 was raised. Amongst the contributions was a ring given by local poet Rose Terry. Beecher took the ring and placed it on Pinky’s finger, telling her “with this ring, I wed you to freedom.”

Documenting the church’s work below street level is, of course, much more difficult than that above it. By its very nature, the Underground Railroad’s history is largely oral. If caught aiding a fugitive slave, the members of Plymouth church would be threatened with $1,000 fines or a year in prison. Beecher himself was threatened repeatedly. One letter to the church contained a drawing of a lynching and a note saying, “Henry Ward Beecher, here is the fate of all traitors. We are making a rope for you.”

But in the face of such violence, the members of Plymouth Church fought tirelessly to help the escaping slaves. In his memoirs, written in 1880s, Committee of Vigilance leader, and conductor on the Underground Railroad Charles Ray explicitly mentions that fleeing slaves were taken to and hidden at Plymouth Church. With no attic, closets or secret rooms, it seems likely that the slaves were given sanctuary in the chambers underneath the church. “With no written records, this is our assumption,” says Rosebrooks.

There is, however, evidence for the mock slave auctions, although the exact number held at Plymouth Church is unknown. The church records of the treasurer account for at least 7 groups of people between 1854 and 1860, and that the monies raised to buy their freedom ranged from $500 to over $10,000 for one woman and her seven children.

Today Plymouth Church remains a thriving ministry in the heart of old Brooklyn Heights. As well as an attached school, the church maintains a well-appointed exhibit telling the story of the remarkable events that took place here, both in public and underground. Perhaps the most remarkable artifact in the exhibit is the plain ruby set in a ring of 18 carat gold that Rose Terry gave to Beecher on February 5th, 1860 and which Henry Ward Beecher placed on the finger of Pinky, buying her freedom. Pinky moved to Washington, D.C. where she grew up to become a teacher helping to educate liberated slaves and married a lawyer. She returned to Plymouth Church in 1927 for the church’s 80th anniversary and gave the ring back to the church. It tells the story of a brave congregation that stood up against the evils of slavery led by their charismatic preacher Henry Ward Beecher. And of the secret chambers underneath the church which are still there today.

Interested in seeing the Plymouth Church and the Underground Railroad for yourself? Book a tour!

Exterior of Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims, Brooklyn. (Photo: Tony Fischer/Flickr)

Exterior of Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims, Brooklyn. (Photo: Tony Fischer/Flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook