Inside the Brutal French Guiana Prison That Inspired ‘Papillon’

Entrance to the Transportation Camp. (All photos: Coen Wubbels)

Entrance to the Transportation Camp. (All photos: Coen Wubbels)

Our guide waits for us while we assemble beneath the words “Camp de la Transportation,” carved above the sole entrance gate of the former penal colony of Saint Laurent de Maroni. This far flung site in French Guiana, an overseas department of France located just above Brazil, was once home to some 70,000 convicts that had been banished from France.

The whole entrance feels too clean, too tidy, too innocent for a place with such a brutish past. Built in 1850 on the orders of Napoleon III, the penal colony, located along the Maroni River, became the arrival and processing point for criminals who had been sentenced to prison and hard labor in French Guiana.

Over a period of almost 100 years, between 1852 and 1946, tens of thousands of convicts lived and worked in Saint Laurent de Maroni. The camp was home to murderers as well as prisoners who were shipped halfway across the world for having committed minor offenses. One of the most well-known inmates was Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish-French officer wrongly accused of treason, who spent four years incarcerated at a notorious prison there called Devil’s Island.

But the prisoner who told the world of Saint Laurent de Maroni in the most memorably gritty detail was French author Henri Charrière, whose incarceration and escape memoir Papillon became a worldwide best-seller when it appeared in 1969. It was later turned into a Hollywood film starring Steve McQueen.

Trail signs in the forest where prisoners were set to work..

Trail signs in the forest where prisoners were set to work..

In 1931, at the age of 25, Charrière was sentenced to life imprisonment and 10 years hard labor for a murder he claimed he never committed. He had been in prison for 11 years before he finally succeeding in escaping. Using a bag of coconuts as a raft, Charrière moved with the tide until he arrived on the shores of Venezuela.

He settled there, eventually becoming a citizen and a restaurateur. The camp and penal colony where Charrière was held in French Guiana became notorious some three decades later, with the publication of Papillon.

Charrière’s book, a combination of his own experiences and those of other inmates, details the brutal life of inmates in the penal colony, his numerous escapes and recaptures, and torturous sentences in damp dark cells, including solitary confinement on Devil’s Island.

Remnants of door bolts that locked individual cells.

Remnants of door bolts that locked individual cells.

The book’s stories of punishments, tight living conditions, dirt and abuse conjured an image of a prison camp that is dark, sinister, and haunting. It is surprising, therefore, to enter a large, open, and sunny courtyard shaded by a big mango tree.

The site underwent extensive renovations in the 1980s, after which it became a Historic Monument in 1994. The original walls, plastered and with peeling terracotta paint, are still intact. Brick columns hold up the shaded patios around the buildings.

Jungle where prisoners were set to work.

Jungle where prisoners were set to work.

While most of the vegetation that engulfed the buildings after the camp closed in 1946 was removed during the restoration, new vines and trees are sprouting from the walls’ fissures again. It is unsafe, and thus prohibited, to enter these buildings. Here, in the tropical climate of French Guiana, anything that isn’t constantly maintained is doomed to rot away very quickly. The buildings are now protected by new aluminum roofs.

We move on to a long wall on the left-hand side, labeled “Blockhaus 1” and painted pink with small, barred windows along the top. The guide uses a key to open a wooden door which leads to the second section of the transportation camp. Here the energy is different, the air heavy. It is here, behind a locked door, that the true horrors took place. Despite the renovations, this part of the site remains an eerie place.

The barracks containing the prisoner’s sleeping quarters.

The barracks containing the prisoner’s sleeping quarters.

The prisoners—bagnards—worked from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. They constructed their own jailhouses with bricks made of the local red clay, as well as all other buildings in the colony, including the hospital, courthouse, jailhouse, and the railway to the sub community of St. Jean. Jobs varied from hard labor such as logging wood, cutting cane, and construction to the less strenuous jobs like household work or maintaining the gardens outside the jailhouse.

The camp was organized according to classifications. The guide leads us along the different sections of the Quartier Disciplinaire—the disciplinary quarters. On the right side, serious criminals lived in barracks with about 40 people. On the other side, other convicts had their own section, also with collective cells containing rows of concrete beds along the walls. At night their feet would be bolted to a metal bar.

An individual cell for the more dangerous prisoners.

An individual cell for the more dangerous prisoners.

The most dangerous prisoners had their own, claustrophobic cells of about 1.8 by 2 meters. Some are ghostly-looking with vines and fig roots entangling the walls, others have been restored. The convicts slept on planks with a wooden block for their heads and with leg shackles.

Even released bagnards lived here, in a separate section. Anybody who had completed his sentence had to stay another five years in the colony of French Guiana, which was Napoleon’s solution to developing the colony. Until they had earned enough money to live outside the jailhouse, or to return to France, they lived inside the prison of Saint Laurent de Maroni.

The weathered walls of the barracks remain standing, many of which have been freed of vegetation that was about to tear down the whole structure. Only three large mango trees in the open section between the barracks were allowed to stay. Parts of cell bars and manacles remain in place, most of them corroded. Many doors rotted away or have been removed. The place is silent. People slept here with dozens of others, not being able to turn around because their feet were chained, not having any private space. Even the bathrooms at the far end are just an open space.

Another individual cell.

Another individual cell.

Bodies and spirits were broken here. With so many people living in such small quarters, fighting and death among the prisoners were common. In most cases they weren’t punished. As the guide explained, “Why punish them, which only required paperwork. It was easier to let nature take its course and let them die of harsh labor, tropical disease or a failed attempt to escape.”

When a guard got hurt or killed by a prisoner, the guillotine was brought out into the open section between the two rows of barracks. The execution of the prisoner was done by another bagnard, after which an official would speak the words, “Justice has been served in the name of the republic.”

In the rainforest are still a few graves of old prisoners.

In the rainforest are still a few graves of old prisoners.

Chercher la belle—escape—was in the minds of many inmates. According to the guide, up to 80 percent of attempts failed. Prisoners might manage to leave the prison grounds, but most got stuck in the rainforest. If they succeeded in getting to Suriname or Venezuela and were caught there, local authorities would send them back to the camp.

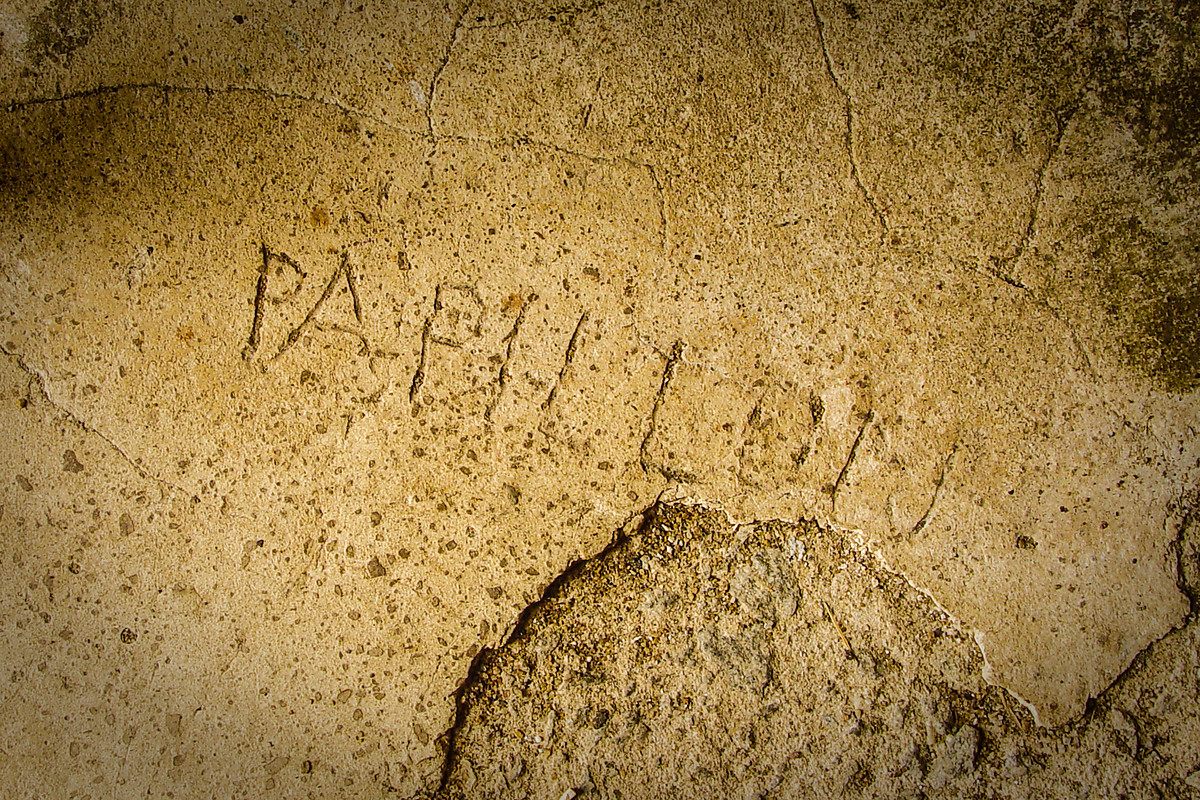

The guide saved the main attraction for last. The one word for which most visitors take the tour—Papillon—is carved into the floor of cell 47, in the far left corner of the Camp de la Transportation. It is testimony that Papillon once lived here.

Papillon’s name carved in the floor of cell 47.

Papillon’s name carved in the floor of cell 47.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook