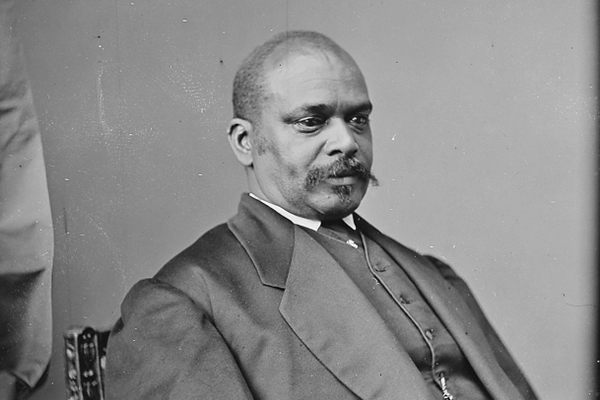

The 19th-Century African-American Actor Who Conquered Europe

And why you might never have heard of Ira Aldridge.

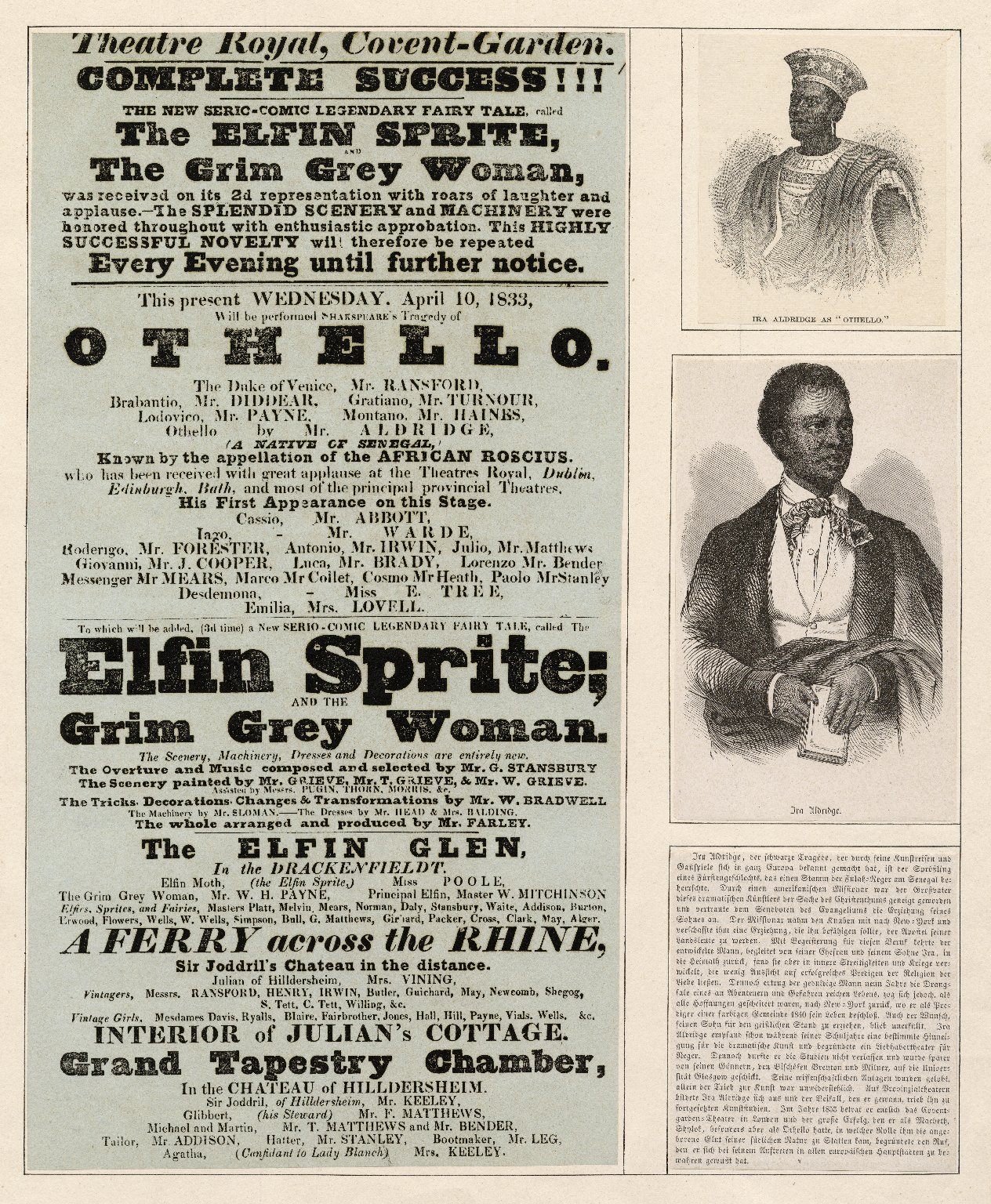

In 1824, a young, black New Yorker named Ira Aldridge set sail for England. Within 10 years, he was performing Shakespeare in London’s Covent Garden. By the time 20 more had passed, he had performed for royalty across Europe, made audiences laugh and weep, and been heralded one of the great actors of his age.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the slave trade flourished, free African Americans and their descendants still weren’t eligible for citizenship, and runaway slaves were supposed to be returned to their owners, no matter which state they were apprehended in.

Aldridge’s career as an actor was exceptional, and not just for a black actor at that time. He traveled farther, was seen by audiences in more countries, and won more medals, decorations, and awards than any other actor of his century. But, somehow, this 19th-century great slips under the radar. He seems to be too American to make it into British or European theatrical histories, and, because he performed almost exclusively in Europe, tends not to appear in American ones. For most of his career, Aldridge traveled from place to place, on short-term engagements that made it hard for him to build a reputation in any one spot. “As a luminary,” writes scholar Bernth Lindfors in the introduction to Ira Aldridge: The African Roscius, “he was more a comet than a fixed star—here today, gone tomorrow—and as a consequence, he shines less brightly now.”

In addition to his career of rare achievement on the stage, Aldridge used his platform and status to fight slavery, even from across the Atlantic. Traditionally, Shakespearean plays ended with what is known as “a jig,” an unscripted “dance song game” that came after the story itself. They might parody the story, or just act a kind of crude farce. Aldridge, on the other hand, used those moments to speak out. At first, he simply played his guitar and sang, but by the time he was 25, in 1832, he began reciting poetry that he had written himself.

I risk my all upon thy power

Life, son, yea, country, too

To free my brethren, fetter’d slaves

From sinking in inglorious graves.

Aldridge’s activism wasn’t limited to the stage. Throughout his lifetime, he also donated significant amounts of money to the abolitionist movement and the Negro State Conventions. Audiences and reviewers took note. A German review of a play mentions his involvement in the story of a family of five slaves who had escaped from Baltimore to New York. “By the power of the [Fugitive Slave Act], the family was captured and was soon to pay a high price for their desire for liberty in the land of freedom.” The family members were scattered across the United States, and the daughters’ fates were uncertain. Aldridge saw the case in the papers and immediately sent a large sum of money to a New York society to help them. “This is the way,” wrote the paper, “in which he uses his income.”

Aldridge was born free in New York in 1807 to a lay preacher and straw vendor, Daniel Aldridge, and his wife, Lurona. His mother died when he was young, and his father hoped his son might follow in his professional footsteps. Instead, Aldridge fell in love with the stage—and with Shakespeare.

At the time, black actors were limited to performing at the African Grove Theater, between Bleecker and Prince Streets in lower Manhattan. The theater was one of the earliest attempts to create a black theater in New York, with a black cast, crew, and (mostly) audience, made up of “free and slave, middle-class and working-class” alike. It was also, apparently, where Aldridge saw his first Shakespeare play, and later made his start as an actor.

But the African Grove couldn’t, or didn’t, last. There are no records of it after 1823, and at least one source claims it was “mysteriously burned to the ground” in 1826. Aldridge seems to have realized that he would never achieve his dreams as an actor as an African American in America, and took the earliest opportunity to leave. “The only recourse for a serious, determined and aspiring young Negro actor was to emigrate,” write his biographers Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock (his daughter). So, at the age of just 17, he accepted employment on a ship headed to England, never to return.

Almost as soon as Aldridge made it to the United Kingdom, he began to distinguish himself. During 18 months of study at the University of Glasgow, he won “several premiums” and a gold medal for excellence in Latin composition. Though he quickly found work at London’s Royal Coburg Theatre—playing the lead role of Oroonoko in The Revolt of Surinam in 1825—the London press was extremely hostile to him, and predicted that he would never find profitable employment on the stage, or posited that a black man shouldn’t be there at all.

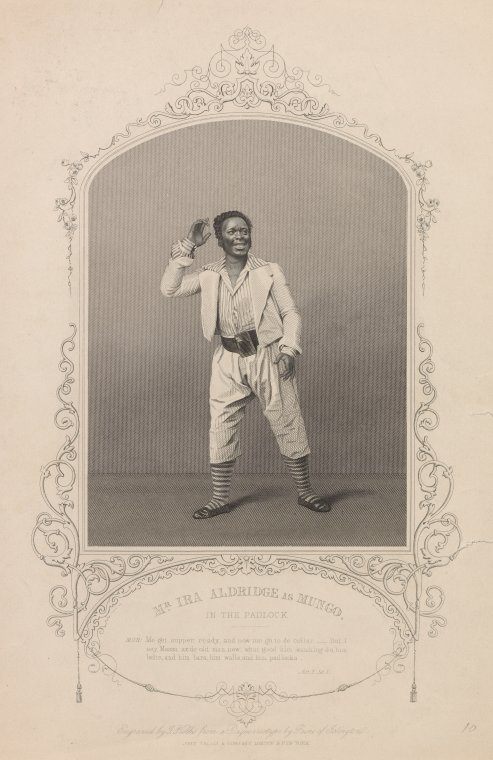

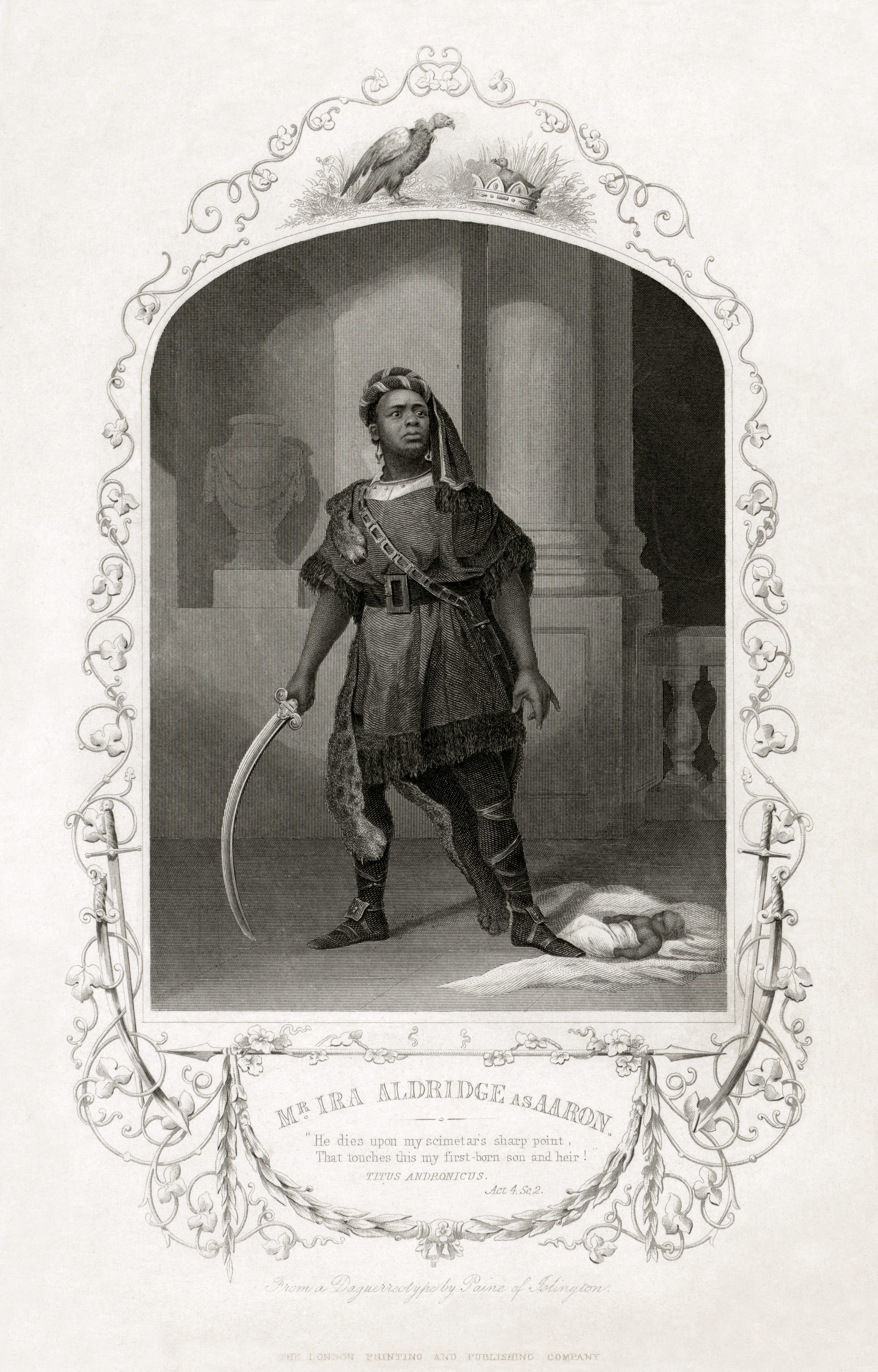

Aldridge then began to tour provincial British cities. For seven years, he went from one town to another—Manchester, Halifax, Edinburgh—playing a variety of “black” roles, including Oronooko, Othello, and Mungo in Charles Dibdin’s The Padlock. Audiences loved him, particularly as he gained experience and confidence. In time, the press eventually came around as well. Back in New York, in 1853, The New York Times quoted a Viennese paper’s review of his Othello: “… an eminent artist, enrapturing as well by the simpleness and truthfulness of his performance in general, as by the power with which he marked the most violent eruptions of passion.” Aldridge never performed in, or returned to, New York after he left.

Soon, Aldridge had exhausted the traditional “black” roles, but, as an able, versatile, and very popular actor, began to play traditionally white ones. (For these, he was often expected to don a wig and white make-up.)

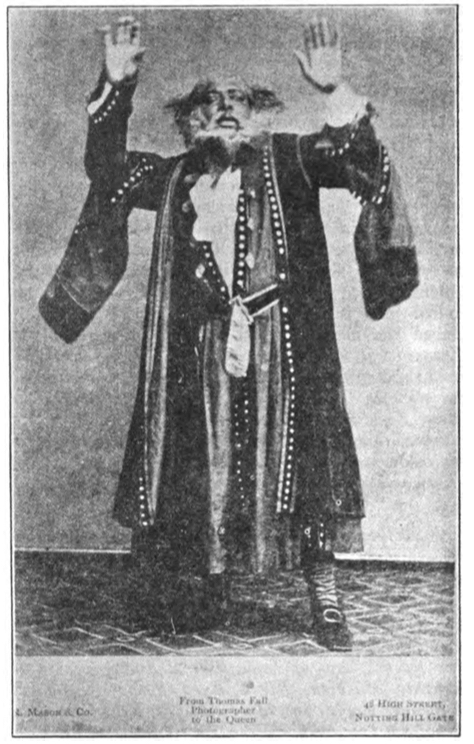

In these, too, he excelled. “When he played Iago in the city of Moscow, in Russia,” priest and historian George Freeman Bragg wrote in 1914, “a number of students who had witnessed the performance unhitched the horses from the actor’s carriage, after the play, and dragged him in triumph to his lodgings. In Sweden and Germany and England, his name was a household word.” Aldridge played Shylock, Macbeth, Richard III, Lear, and a host of other Shakespearean and non-Shakespearean leads.

Even in very strange theatrical contexts, Aldridge shined. In Germany, for instance, he played Othello with an entirely German-speaking cast—he alone spoke his lines in English. A Le Nord correspondent watching the show reviewed it, and him, rapturously. “For the first time, we had seen a tragic hero talk and walk like common mortals, without declamations and without exaggerated gestures. We forgot that we were in a theatre, and followed the drama as if it had been a real transaction.” Aldridge’s talent saw him decorated by royals, and he eventually married one, Amanda von Brandt, a Swedish countess who was his second wife. (He had no children with his first wife, but at least six with three other women, including von Brandt.)

Aldridge died on August 7, 1867, in Poland, two years after slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment. Many of his obituaries, the journal Opportunity noted in 1925, began with the same prophetic, though damning, observation. “… He is the only actor of Color that ever was known, and probably the only instance that may ever again occur.”

Today, Aldridge’s success is celebrated, but in notably limited ways compared to other 19th-century performers, such as Sarah Bernhardt, Ellen Terry, or Colin Firth-lookalike Edwin Forrest. One of the red velvet chairs in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon bears his name, as does a blue English Heritage plate in London. A plaque recently unveiled in Coventry commemorates his time there, during which “he gave a number of speeches on the evils of slavery,” the BBC reports. “When he left, people inspired by his speeches went to the county hall and petitioned for its abolition.”

In the Royal Shakespeare Theatre Ira Aldridge has a seat named after him #blackhistory #aldridgestory pic.twitter.com/MSilf17KjE

— The RSC (@TheRSC) October 7, 2016

Aldridge seems to have been an early example of African-American expatriation—when outstanding black artists left the United States to excel elsewhere. Racism certainly existed in Europe, but there were still more opportunities for them there. Almost exactly 100 years after Aldridge left, the entertainer and activist Josephine Baker went to Paris to make her name. Twenty years later, writer James Baldwin did the same.

The struggle for recognition of African-American actors continues today. Since the Academy Awards began in 1929, only 6.4 percent of acting nominations have gone to non-white actors, and few actual awards. Only four black men and one black woman have ever won Best Actor or Actress. In Britain, things haven’t been much better. British Film Institute research from 2017 found that nearly 60 percent of films produced there in the previous 11 years had no black actors in any role. And several black British actors, such as David Oyelowo, Idris Elba, John Boyega, and Chiwetel Ejiofor have found their mainstream success in Hollywood.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook