The Rare-Book Thief Who Looted College Libraries in the ’80s

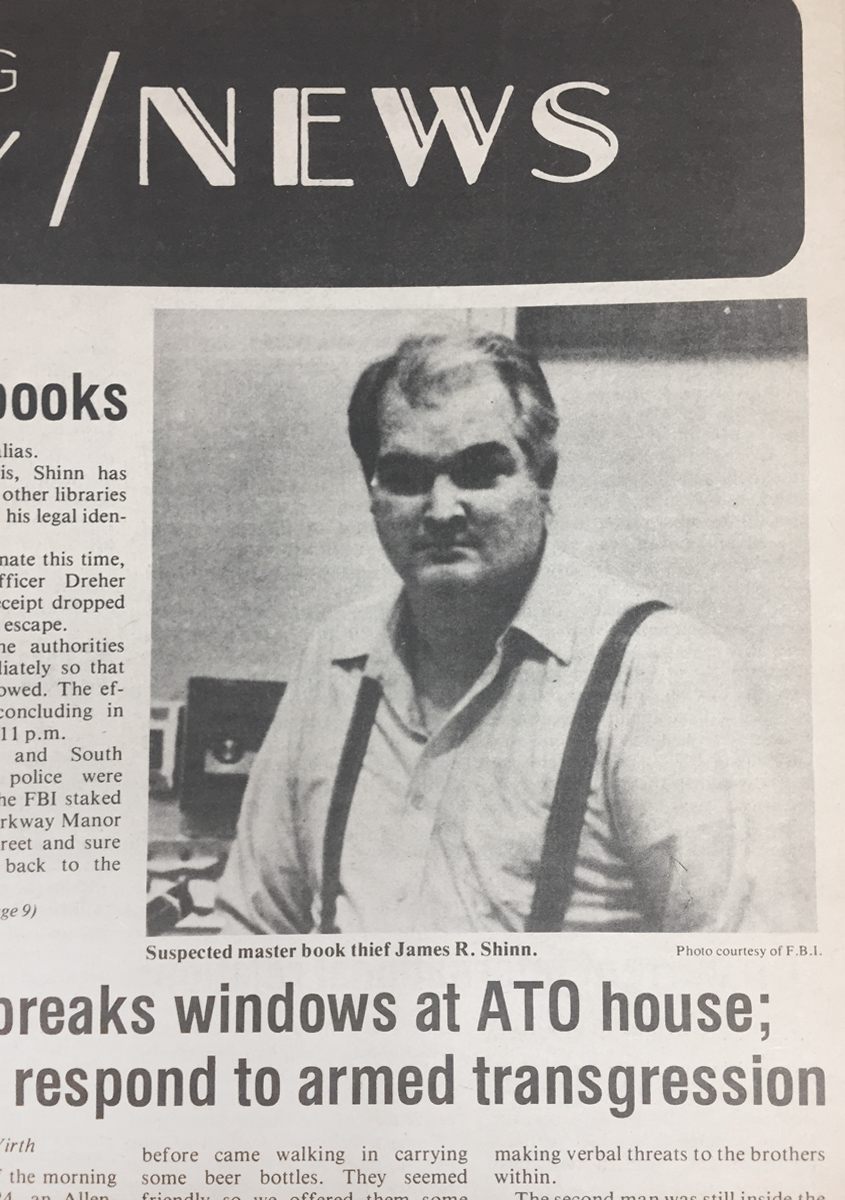

By passing as a professor, James Richard Shinn made off with over $100,000 worth of books.

On the evening of December 7, 1981, Dianne Melnychuk, serials librarian at the Haas Library at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, noticed an unfamiliar gray-haired man of early middle age lingering around the card catalog near her desk. He had attempted to appear inconspicuous by way of nondescript, almost slovenly dress, but at almost six-and-a-half feet tall, with a 225-pound frame, he stood out.

Something about him rang a bell. Melnychuk discreetly followed him up to the sixth level of the stacks, and carefully observed him from the end of a row of shelving. In spite of the glasses he wore that evening, his face clicked in her memory.

A few months earlier, a photo of this man, who went by the name James Richard Shinn, had appeared in an article published in Library Journal. Patricia Sacks, director of the Muhlenberg and Cedar Crest College Libraries, had shared the article with her staff with an accompanying memo: “Take a good look at the face,” she wrote, “and, more importantly, keep your eye on strangers whose behavior may be a tipoff.”

James Richard Shinn was a master book thief. Using expert techniques and fraudulent documents, he would ultimately pillage world-class libraries to the tune of half a million dollars or more. A Philadelphia detective once called him “the most fascinating, best, smartest crook I ever encountered.” And yet, despite the audacity of his approach and the widespread effects of his crimes, Shinn has been relegated to a footnote in book history.

On that December evening, Melnychuk returned to her desk and waited to see if Shinn would approach. Possibly alerted by her inspection, however, he descended from the stacks abruptly and left the building. She reported the sighting to Sacks, who alerted campus security and the Allentown office of the FBI.

Shinn was not deterred. Just over a week later, on the evening of December 16, librarian Dennis Phillips spotted him entering Haas Library from his vantage point at the reference desk. Shinn again headed for the stacks, and Phillips called campus security. The security chief and two officers arrived, and the police and FBI were alerted. The security officers escorted Shinn to a library office where they began to question him. Shinn fumbled in his pocket for cigarettes and asked if he could smoke; as the distracted officers sought to find an ashtray, Shinn bolted out of the office and the library and disappeared. Beneath his chair, dropped as he reached for his cigarettes, were an Illinois driver’s license with his photograph and alias and a receipt for the local motel in which he was staying. Police and FBI agents staked out the Park Manor Motel in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania and arrested Shinn upon his arrival at 11 p.m. His wife, Lola, was questioned but not detained.

Shinn’s motel room contained 26 stolen books and a file full of inventory cards for another 154 volumes. He was well-educated in book history, restoration and binding, and the tools of his trade filled the room: color-stained cloths and Q-tips with jars of shoe polish, used to color-match and conceal library markings on book spines. A folder of facsimile title pages, used as replacements when a book’s true title page was stamped or contained other identifying marks. All were designed to remove libraries’ marks and render the stolen works unidentifiable and thus saleable to unsuspecting book dealers and collectors. Additionally, Shinn’s tool kit included stolen license plates, false ID papers, manuals for safecracking and disarming alarms (as well as a guide titled “How to Disappear and Live Freely”), and a 32-caliber pistol.

Shinn had been busy: his photograph had appeared in Library Journal in the first place because in April 1981, he had been spotted in Oberlin College’s Mudd Learning Center passing a metal detector over books and placing volumes into a briefcase. William A. Moffett, the College’s library director, asked Shinn for identification, and when he failed to produce any, Moffett called campus security and the local police. A search of Shinn’s room at the Oberlin Inn uncovered 63 books belonging to Oberlin, four from the University of Pennsylvania, and six from the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia; the cumulative value of this cache was approximately $30,000. Shinn was charged with five counts of shipping and receiving stolen property, and when released on $40,000 bail on April 29, had promptly disappeared.

Shinn spent the night of December 16, 1981 in the Lehigh County Jail, was arraigned, held on $100,000 bail, and transferred to Philadelphia on charges filed by the University of Pennsylvania and the Lutheran Seminary related to the books found in the Oberlin cache.

Born James Richard Coffman on October 25, 1936 in Indiana, Shinn was on the move early—he was picked up as a runaway in Los Angeles at the age of 16 and returned home to Muncie, Indiana. Through his thirties and early forties, Shinn accumulated a record of burglaries and armed robberies that focused more and more on antiques and rare books. In 1972 he was arrested in California for a home burglary of statues and jewelry; the same year, he held up an Illinois antiques dealer for items amounting to $30,000. In 1973, Shinn was arrested in Philadelphia in possession of $300,000 worth of rare stamps. In successive years, he increased his connections with legitimate book dealers as he conned them into shipping him merchandise for which he never intended to pay. Under the names of “Charles W. Baker” and “Richard V. Allen,” Shinn moved in the rare-book trade, issuing mail-order catalogs of stolen material and frequenting antiquarian book fairs, dealing only in cash.

By the time of his Bethlehem arrest on December 16, 1981, he was wanted in California, Ohio, and Pennsylvania on charges of theft from academic libraries. Gene Caulden, one of the Philadelphia major crimes detectives who spoke at length with Shinn in 1973 and again in 1981-82, said of him in a Los Angeles Times article: “He speaks quietly and is controlled. He’s gentle and never raises his voice. He has rumpled white hair and wears suspenders. His shirt tail is usually hanging out and he’s always sloppy, kind of a rustic look like a professor … He’s low key. And he never carries identification. That way, even if he’s stopped, they figure he’s just a sloppy bum stealing a book.”

Shinn based his home and operations in St. Louis, Missouri, but lived on the road, moving with Lola from motel to motel. “Our lives would make a good novel,” she told a Bethlehem Globe-Times reporter shortly after Shinn’s arrest in December 1981. “In fact, I think it would take two novels to write all about it.” For six weeks prior to the arrest, they had been living in area motels, where she had joined him for the first time since he had jumped bail in Ohio in April. Lola would watch soap operas all day, while her husband visited local college libraries, because “Jim likes to read.” She was indignant about the $100,000 bail; “It’s not like Jim hurt anyone or did anything violent. What’s so wrong about going into a library and taking books off the shelves? People take books from libraries all the time.”

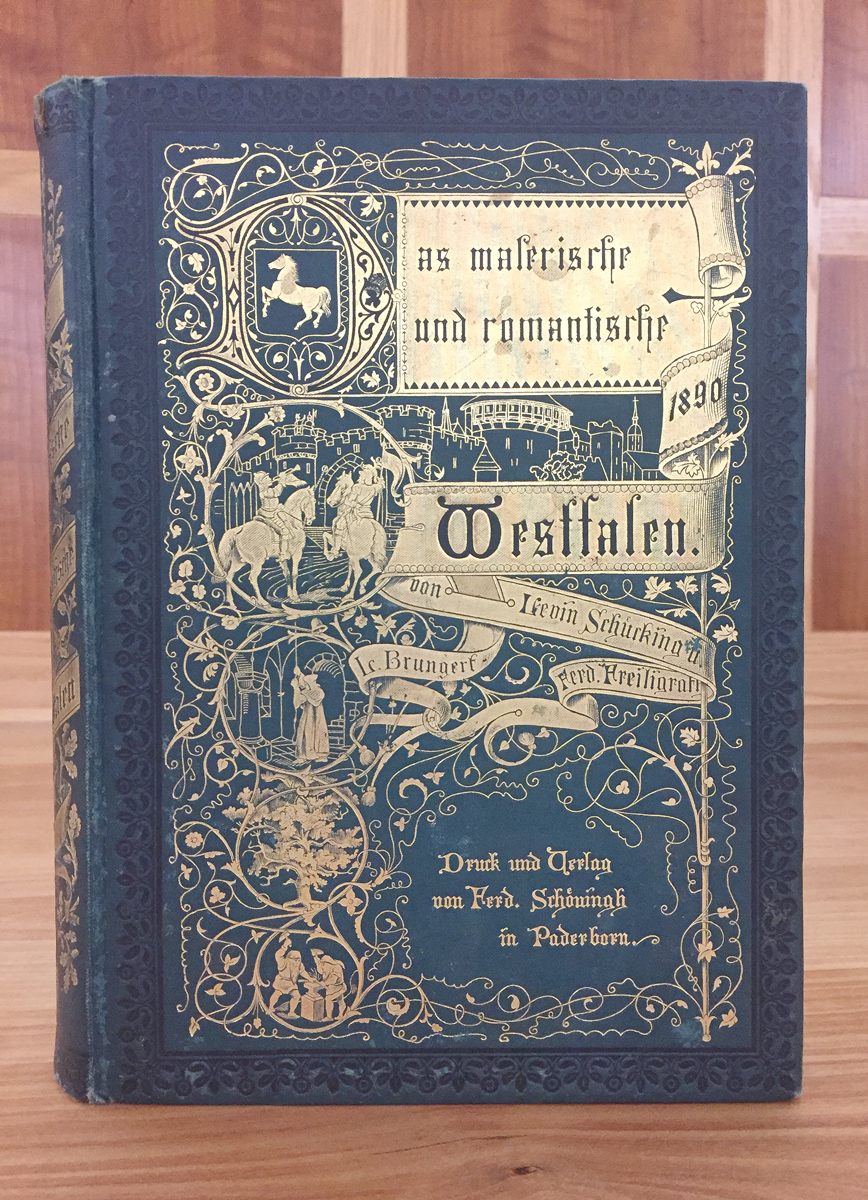

Far from casual, James Shinn’s approach was premeditated. It is believed that he would compile a “want list” of valuable books by reading library journals to find titles of value. Next, he would scan the National Union Catalog to determine which libraries held the desired items. He made an extensive study of library security techniques that allowed him to accumulate tools and tricks to avoid them. And he rarely bothered with a book valued under $300.

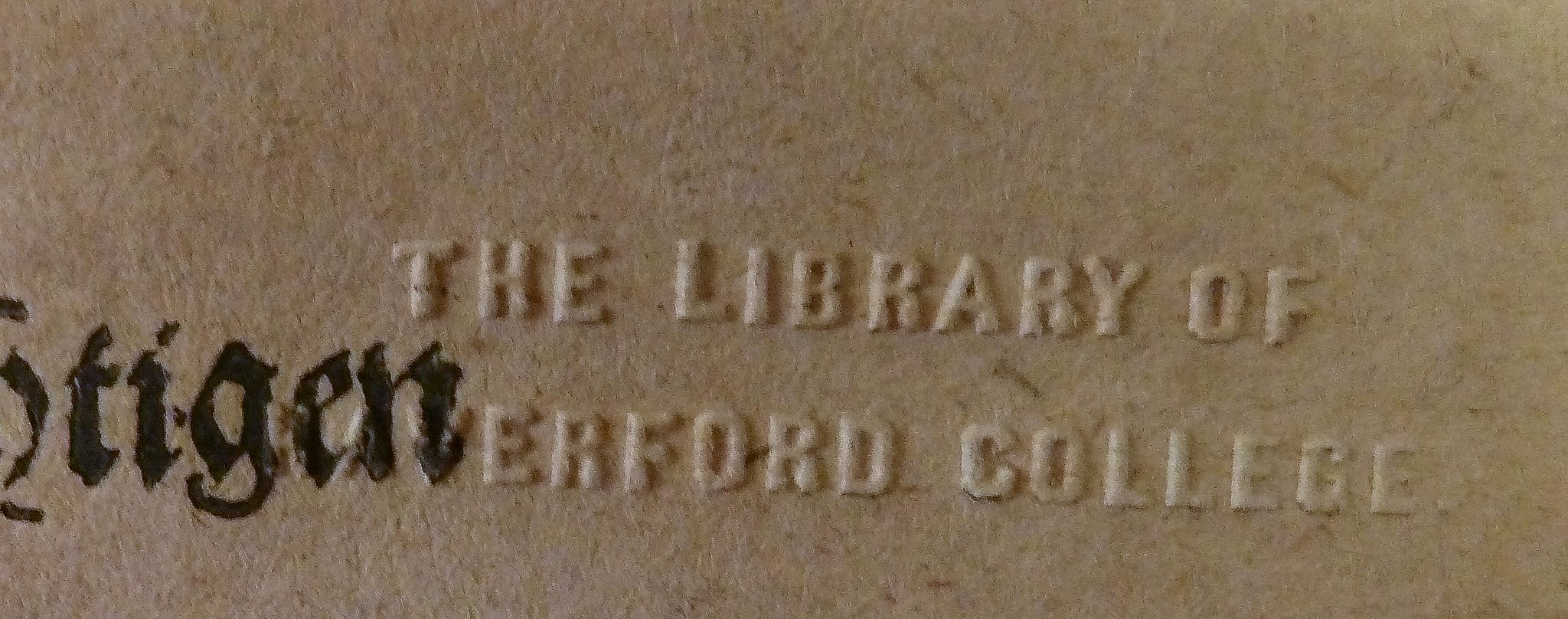

A month after Shinn’s arrest at the Bethlehem motel, the FBI received a call from a local man who rented storage lockers; he had spotted Shinn’s face on the news and recognized him as a customer. On January 15, 1982, 16 footlockers containing over 400 books were seized from the Bethlehem storage unit. The trunks had apparently been shipped from “Charles W. Baker” in Rantoul, Illinois to “Charles W. Baker” in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Patricia Sacks, already working with her staff to identify and return the 26 volumes found in Shinn’s motel room, was asked to help; over the next two years, she and her staff dedicated over 500 hours to the identification and return of the stolen materials—including the 12 volumes stolen from Muhlenberg.

Only 20 to 30 percent of the volumes still contained library markings, but over time it was determined that the books originated from UCLA, Princeton, the University of Michigan, Stanford, Lehigh, Carnegie-Mellon, Haverford, Bryn Mawr, Johns Hopkins, and other institutions across the country. The cache was valued anywhere between $100,000 and $500,000. Shinn’s “collecting” tastes centered around 18th- and 19th-century travel books and illustrated volumes on natural history whose plates could be extracted and sold individually—virtually untraceably.

On February 24, 1982, Shinn was indicted on two criminal counts of interstate transportation and receipt of stolen property—not on charges of library theft—and he ultimately pled guilty on July 20. He received the maximum sentence of two 10-year terms to be served consecutively. Within a few months, after a promise of immunity, he revealed another cache of books stored near St. Louis, which also needed identification.

“We as a profession are indebted to Shinn,” said Oberlin’s William Moffett, addressing a gathering of the American Library Association at the time of Shinn’s guilty plea. “He has demonstrated the vulnerability of the academic libraries—and it was a lesson we needed.” Thefts, difficult to discover unless a specific book was requested and found missing, were often not reported for fear that a library’s weaknesses would be exposed and its staff would be deemed incompetent. “Each of us must combat the innocence, ignorance, complacency, and indifference that block us from pursuing meaningful and effective measures to prevent library theft,” advocated Pat Sacks in a 1983 lecture. Locking windows, alarming access points, strengthening electronic detection equipment, and restricting access to rare materials all comprised a multi-faceted approach.

On April 27, 1982, Pennsylvania Governor Dick Thornburgh signed into law the Archives, Library, and Museum Protection Act, which finally made library theft a criminal offense in Pennsylvania. A third offense is considered a felony, regardless of the value of the material stolen. In September 1983, the “Oberlin Conference on Theft” welcomed representatives from leading research libraries, the FBI, the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, and members of the United States Judiciary Committee and the Canadian government back to the scene of one of James Shinn’s arrests. Its goal included drafting model legislation for states and the federal government to declare books and manuscripts as pieces of national heritage with stronger legal protections against their theft.

James Shinn was paroled on August 8, 1995, and appears to have lived quietly until his death in 2005. Deemed by William Moffett “the most active professional book thief in the history of America,” Shinn raised the stakes of both library security and library theft. Because of his work on the Shinn case, Moffett discovered a calling in tracking bibliomanes; he became a leading voice in protection and detection until his death 25 years later. On the other hand, Shinn’s crimes and reputation (his total library thefts are estimated to have neared a million dollars) goaded and inspired bibliomaniac Stephen Blumberg, who in 1990 was arrested in possession of almost 24,000 stolen rare books and manuscripts, worth over $5 million. Blumberg considered himself a collector, a book-lover. When interviewed by Nicholas A. Basbanes for his book A Gentle Madness, Blumberg claimed to be “fascinated…like a moth being drawn to a flame. I was fascinated by Shinn’s undoing, but I didn’t admire him. I thought he violated the books. He was in it for the money.” A questionable ethical distinction, to be sure.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook