The WWI Memorial That Refuses to Glorify War

There are countless monuments to the Great War in France, but Paul Landowski’s “Les Fantômes” is unlike any other.

It is the eeriest war memorial you will ever behold.

Actually, I’ll just go ahead and say it’s the eeriest memorial you’ll ever behold. Of any kind.

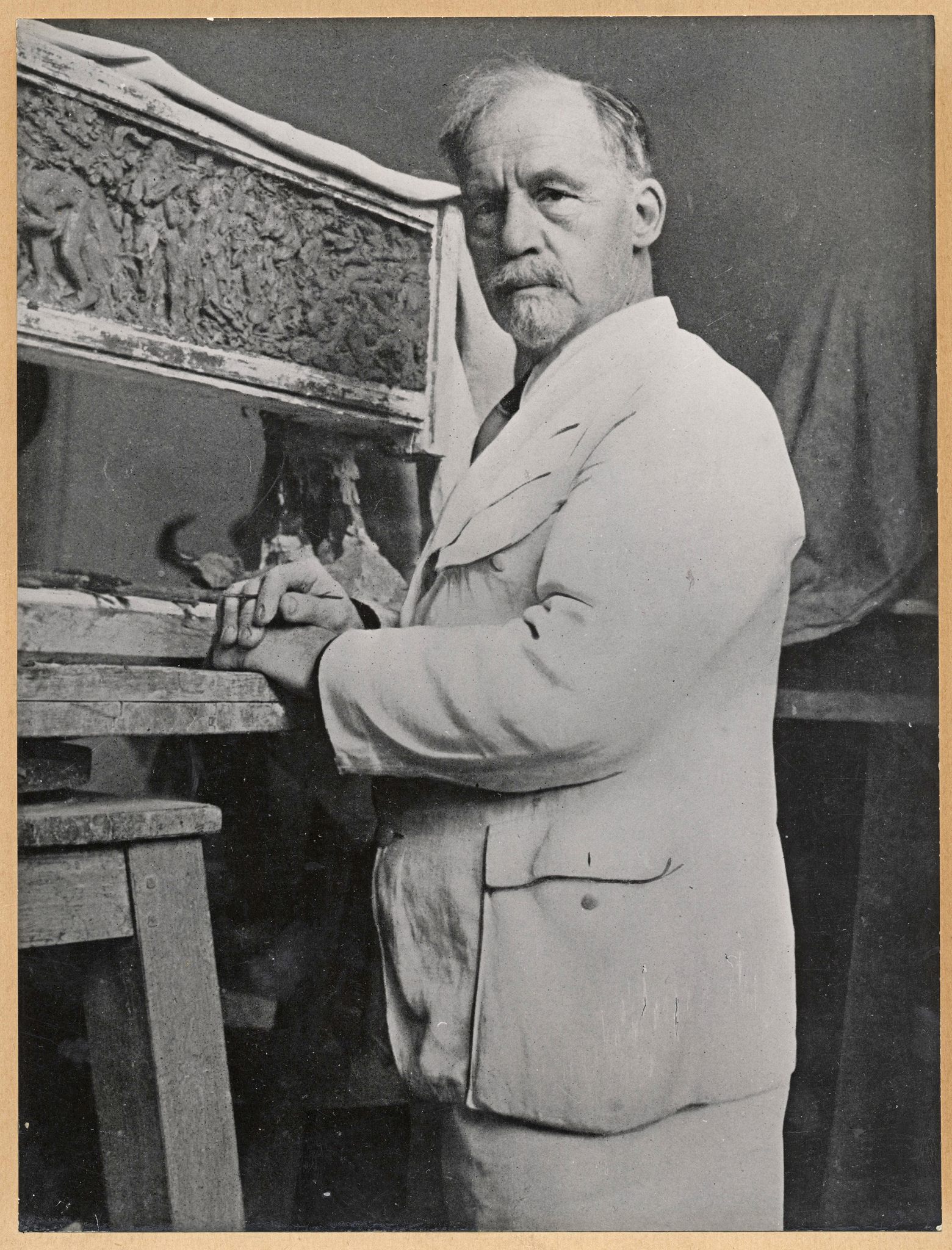

You can thank Paul Landowski for that. Born in Paris to a French mother and a Polish immigrant father, Landowski was 39 years old when his unit, the 132nd Régiment d’Infanterie, was mobilized on August 6, 1914, at the very start of the Great War. He spent four years at the front, was awarded a Croix de Guerre in 1917, and somehow managed to survive. After he was discharged on January 9, 1919, Landowski returned to his home and to work, but he couldn’t seem to forget, or even to distract himself much. What haunted him most was the sight of so many dead poilus—French soldiers—piled up in trenches, stacked in mass graves. Though the trenches were now empty and the graves filled in, he could not get away from those images, the bodies, the faces. So he decided to work with them.

Landowski was a sculptor. Today he’s best known for Christ the Redeemer, that enormous 1931 art deco statue of Jesus that you see in just about every photo of Rio de Janeiro, but he was already a celebrated artist well before the start of the First World War. In 1920, when he was asked to create a memorial to those killed in the Second Battle of the Marne, he immediately thought of those images, those bodies, those faces. He knew that they haunted millions of other people, too, and that even those who had never seen such things—who had never gotten close to the front—were haunted by the vacant bedroom, the unfilled seat at the dinner table, the framed photo next to the polished shell casing on the mantelpiece. France was filled with emptiness. The only way to exorcise it, Landowski determined, was to acknowledge it.

If this seems obvious now, it certainly wasn’t then. There are Grande Guerre monuments absolutely everywhere you go in France, and not by happenstance. After the war, the French government offered funds to every settlement in France—every city, town, village, hamlet, community—to build a Grande Guerre memorial. I’ve been told that in the entire country, from the North Sea to the Mediterranean, only five settlements declined to do so. I cannot name any one of those five, and I’ve never met anyone who can, but even if they do exist, the participation rate was still, effectively, 100 percent.

Regarding the monuments themselves, though, there is little in the way of uniformity: there are steles and tablets, boulders and blocks, fountains and planters. The most memorable are the statues—and here again, there is a great deal of variety: men alone; men with each other; men with Marianne, the feminine embodiment of France. There are men charging, marching, standing still, lying down; their pistols drawn, bayonets thrust forward, hands empty, arms filled with a fallen comrade; mouths agape, lips pursed, gaze intent, eyes closed; alive, dying, dead. In the village of Sauvillers-Mongival, there’s a terra cotta sculpture of a life-sized, grim-faced poilu, hunkered down behind a machine gun, finger on the trigger. You won’t see many of those; it’s not a terribly romantic image.

And that’s the one thing that almost all French Great War memorial statuary has in common: romanticism. Not a trace of fear in the men’s faces, even the dying. They clutch their chests, thrust their arms out toward heaven, call out for their men to carry on!, stare out at the battle still underway. But they are not afraid. They do not experience regret. They may be a few seconds from death, but they are still fiercely alive, and looking only forward, never back. Even the dying figures seem more vibrant than I feel some days, and more noble than I am on my best ones.

That’s not what Landowski was going for. Rather than gone to a better place, he focused on: gone. Those empty dinner chairs, vacant bedrooms. He worked in granite, not marble or terra cotta. It took him 15 years to create eight figures, each standing in for roughly 170,000 poilus killed. They huddle together, eight towering stone men around 25 feet tall, arms hanging down, heads listing forward or to one side, eyes neither open nor closed. A Lebel rifle rests against one; another cradles a machine gun to his chest. The figure next to him carries two sacks full of grenades. Another rests his fingertips on a pick handle. A couple of them still wear their packs. Seven are in uniform; one appears to be naked. They are dead, but alive, but dead. Gone, to be sure, but definitely still right here. He called them Les Fantômes—the phantoms.

As striking as the sculpture is its setting, a hill called the Butte Chalmont near the village of Oulchy-le-Château, about 60 miles northeast of Paris. Like much of the area, Butte Chalmont and the surrounding fields saw terrible fighting during the Second Battle of the Marne. The butte itself caught so many big shells that its shape was changed dramatically and forever. Landowski had to install a series of steps at several points along the path just to make it traversable; the final 50 yards or so required a large staircase, dozens of steps, to scale what had been craters. From the top platform you can turn around and behold a stunning plain that stretches out for miles, dotted with groves and farms, like something out of a fairytale. It’s one of the most beautiful vistas in France. The gentleman who first brought me to see Les Fantômes told me the spot is popular with families, who come in summers and on weekends with blankets and pique-nique baskets.

If a place where legions of men were shot and blown up a century ago, and where their granite ghosts now stare down at you from on high, strikes you as an odd spot for a picnic, no matter how lovely the view—well, I can’t argue with you. It wasn’t the first thought that came to my mind, either. Then again, if you were going to rule out any place men fought and died during the First World War as picnic grounds and parks, you’d be taking an enormous chunk of northeastern French real estate off the table. And this, after all, is what those 170,000 times eight poilus died for: to keep France France. If their descendants couldn’t use this land as they pleased, they might have told you, then they themselves might as well have ceded it to the Germans.

And their memorial would have looked quite different.

Richard Rubin’s newest book is “Back Over There,” a personal journey back to the French rural landscape where so many American soldiers fell during World War I.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook