Leave Your Screens Behind (Mostly) at Rare Book School

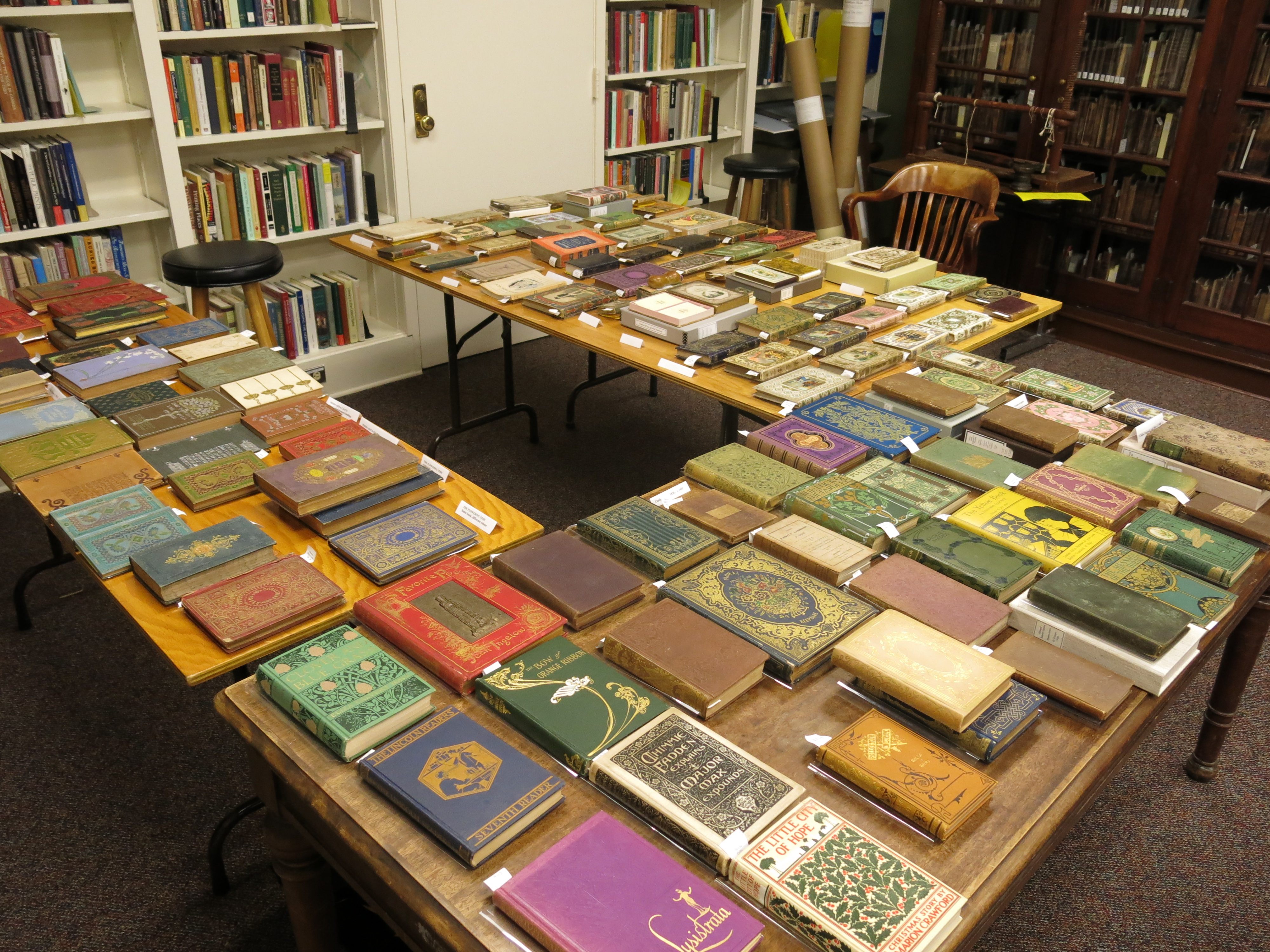

Nineteenth-century bindings from the RBS teaching collection displayed for a session of “Introduction to the History of Bookbinding.” (All photos: Rare Book School)

When summer rolls around, thoughts turn to how to spend the limpid months: Umbrella drinks by the pool? Backpacking through pristine wilderness? A digital detox?

But if you’re a certain kind of person, your dream destination might be Rare Book School in Charlottesville for a week of courses that include “Book Illustration Processes to 1900” or “The Handwriting & Culture of Early Modern English Manuscripts.” Rare book fanatics study not only the words on the page but also the way books were made in order to unlock a deeper cultural understanding of text. And while there are similar programs around the world, Rare Book School offers something they do not: A permanent space and a teaching collection of 80,000 items from books bound in supple goat leather to old Macintosh computers.

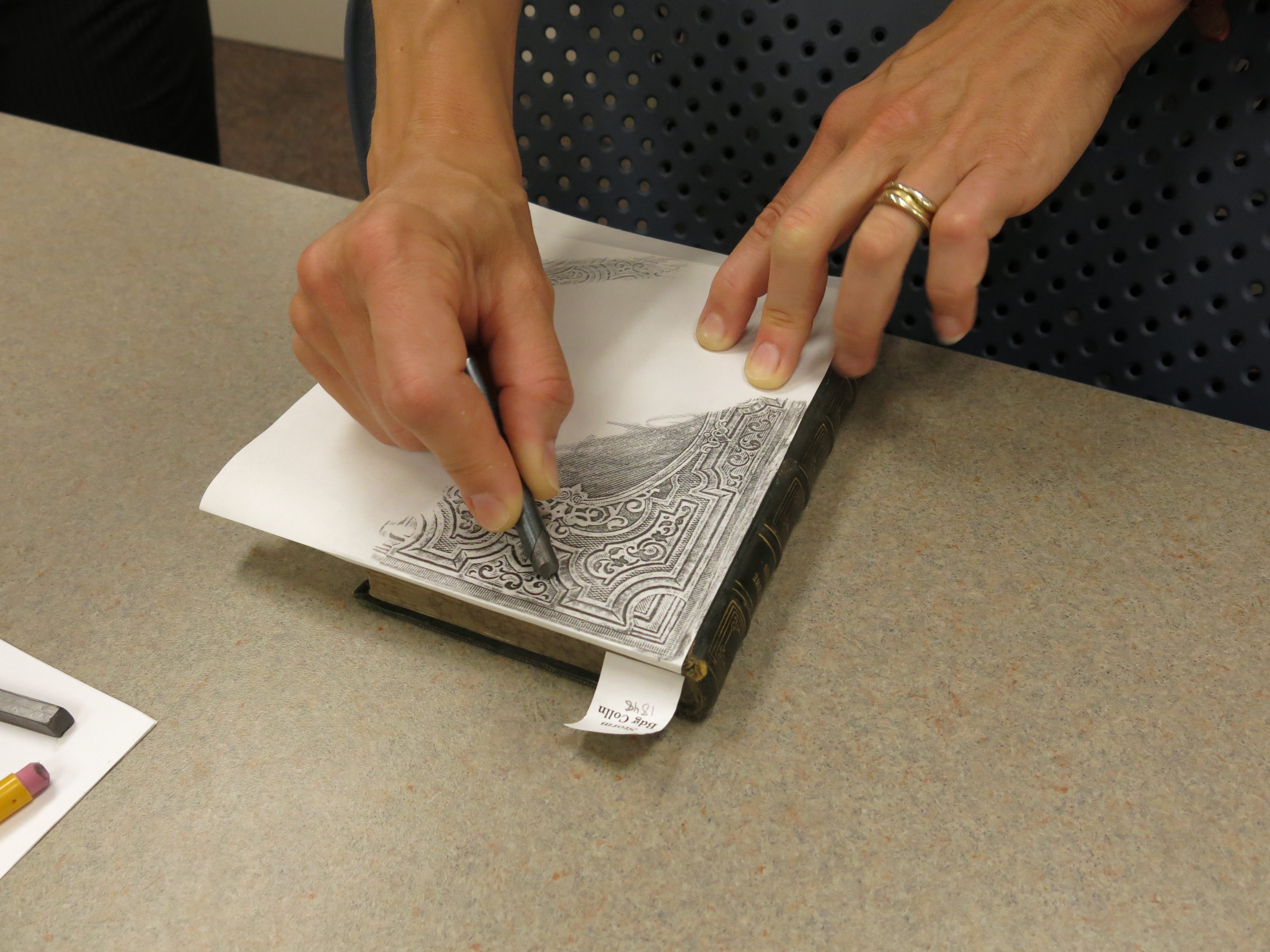

A student in “Introduction to the History of Bookbinding” makes a rubbing of a nineteenth-century binding design.

Rare Book School was started at Columbia University in 1983 by Terry Belanger, who also created a groundbreaking master’s program for rare book and special collections librarians. In 1992, he accepted a position at the University of Virginia and the Rare Book School went with him. Several five-day sessions are held in Charlottesville in June and July, and a few during the spring and fall. Each session typically offers a different roster of five to six courses. Acceptance is competitive—the school has proved so popular that it now offers satellite sessions around the country. In 2015, there were over 800 applicants for about 425 spots in the spring and summer sessions.

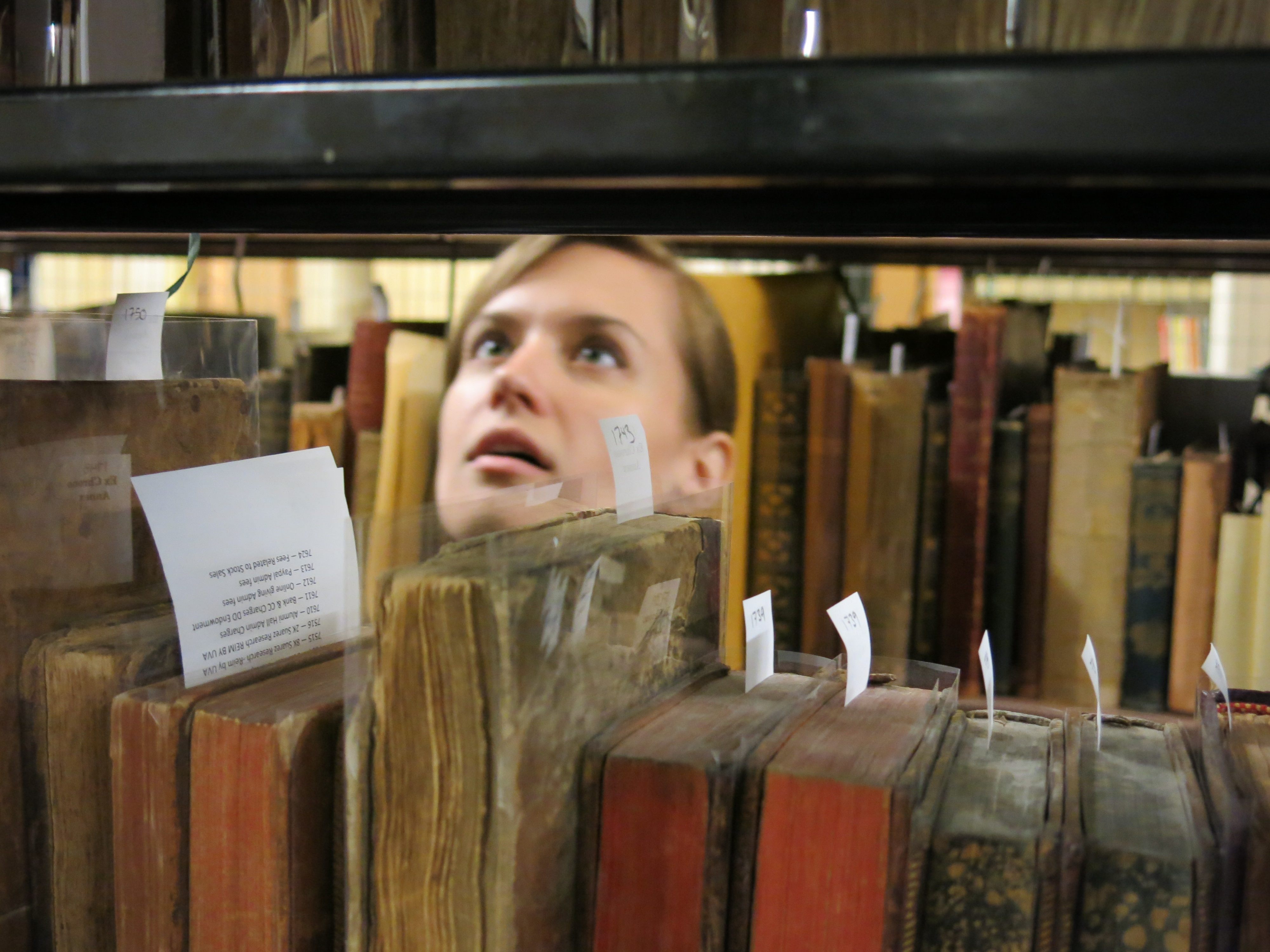

A student in “Teaching the History of the Book” explores the RBS teaching collections.

At Rare Book School students learn about the history of rare books and research techniques, but they also get their hands dirty. They write with quill pens, set type and make etchings and relief cuts. (One course description assures nervous students that “No artistic talent is assumed or expected.”) They are often librarians, academics, antiquarian book dealers or otherwise hail from the book world, but the school has also accepted lawyers, a Facebook employee and a high school student.

RBS Director of Programs & Education Amanda Nelsen demonstrates binding technique for the students in “The Printed Book in the West to 1800”.

“Rare books can be any number of things,” says Jeremy Dibbell, a librarian, Rare Book School student, and director of communications and outreach for the school. “Sometimes it’s old, but not all old books are rare.”

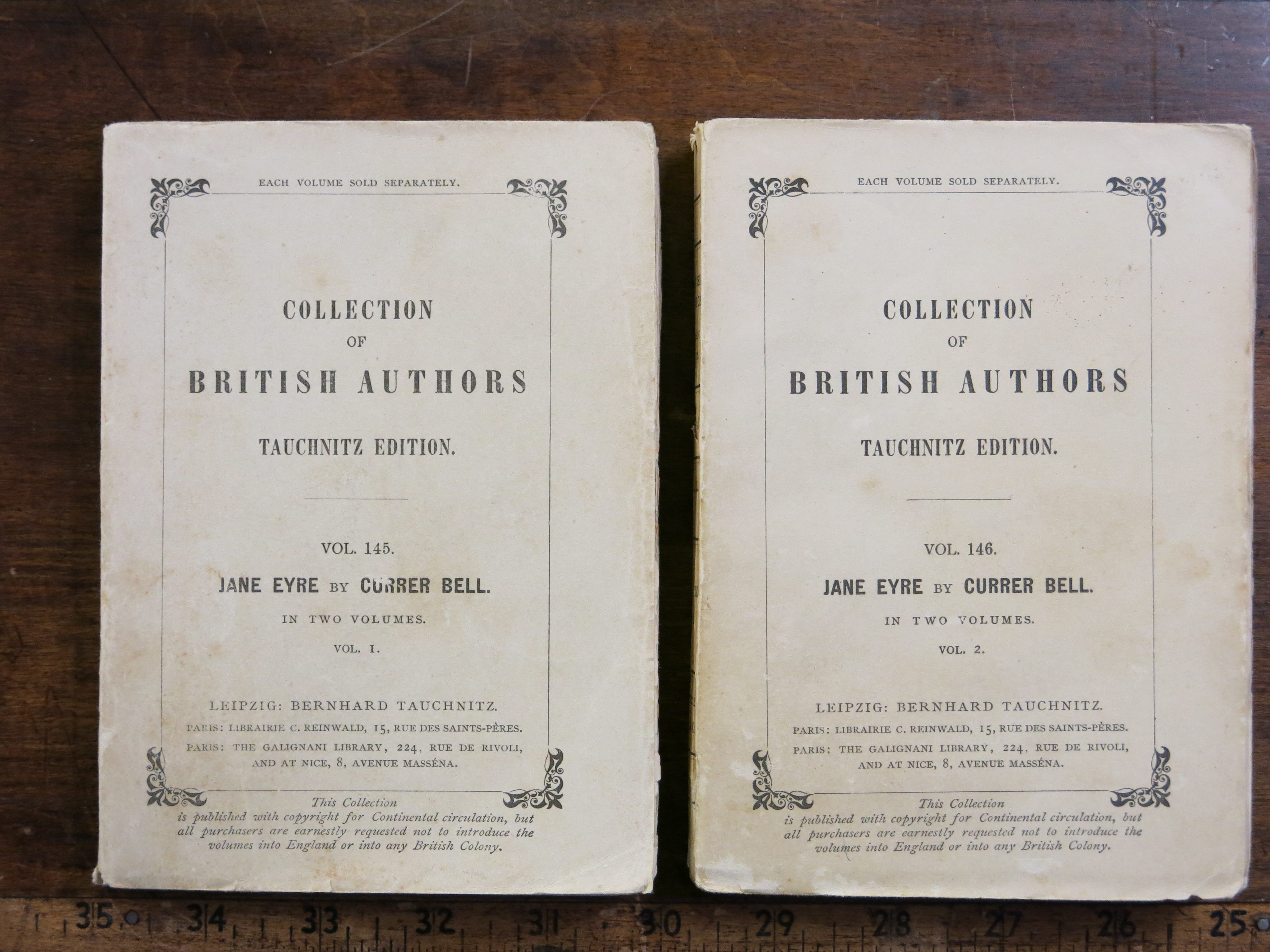

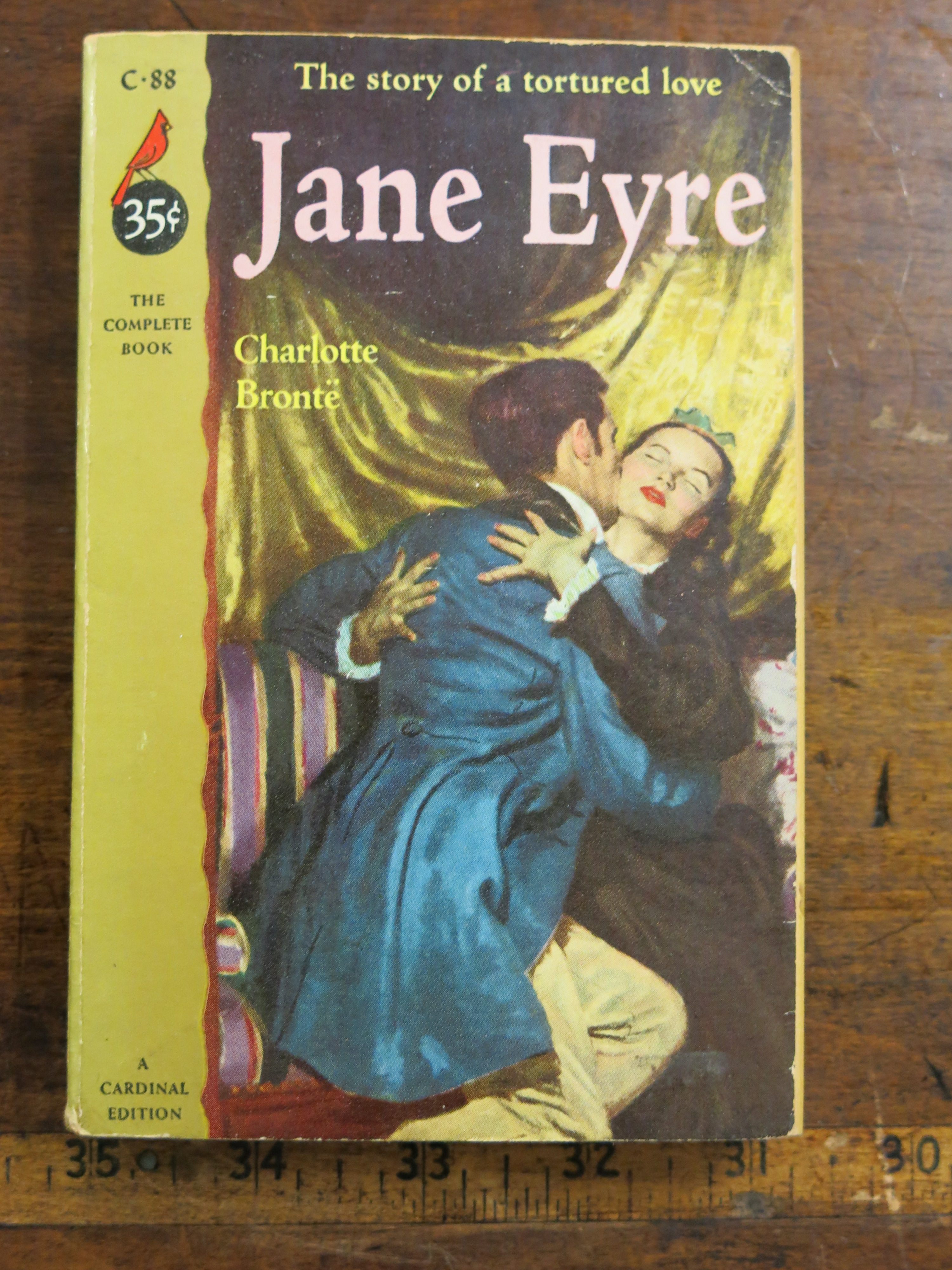

Just two of several hundred copies of various editions of Jane Eyre in the RBS teaching collections.

By definition rare books are scarce—sometimes there are lots and lots of copies of an old book. And not all rare books are necessarily valuable; factors such as condition play into their monetary worth. Provenance matters, too. An otherwise unremarkable book with George Washington’s signature in it suddenly becomes desirable.

“We are interested in all of those and we are also interested in how physical books come to be,” says Dibbell.

The school’s wide-ranging collection includes a book made of straw from 1800 and a copy of the Nuremburg Chronicle, a world history published in 1493. They’ve collected hundreds of different copies of Jane Eyre, first published in 1847. Through the different covers, Jane evolves with the times. On one pulp paperback, she passionately embraces her suitor, eyes closed tight and lips painted a sultry red. The school has also amassed “lots” of copies of “The Tent on the Beach,” a “terrible” 19th century poem, according to Dibbell.

A cover of one of the copies of Jane Eyre in the RBS teaching collections.

So why collect it?

Because bookmaking was once an incredibly physical process that involved everything from binders to “vatmen” who dipped paper molds into vats of slurry. And the binders who sewed “The Tent on the Beach” often left notations in the bindings, which leaves clues for researchers not just about how the books were made but even how authors and publishers interacted.

RBS instructor John Kristensen (at left) and students set typographical ornaments as part of Ornament Night, organized by John Kristensen and Katherine Ruffin for their course “The History of 19th-& 20th-Century Typography & Printing”.

Which is not to say that Rare Books School hasn’t evolved past paper slurry and quill pens. In 1984 the school offered its first tech course, “Microcomputers For Rare Book Libraries.” Now the school has dived headlong into the effort to get their students thinking about how to deal with born-digital archives. And that’s why old computers live alongside delicate books in the collection.

“We turn them on and see what happens,” says Dibbell. “Sometimes smoke comes out the back and that’s a bad thing. But sometimes they boot up and you’re able to take a look at what’s on there and what that tells you.”

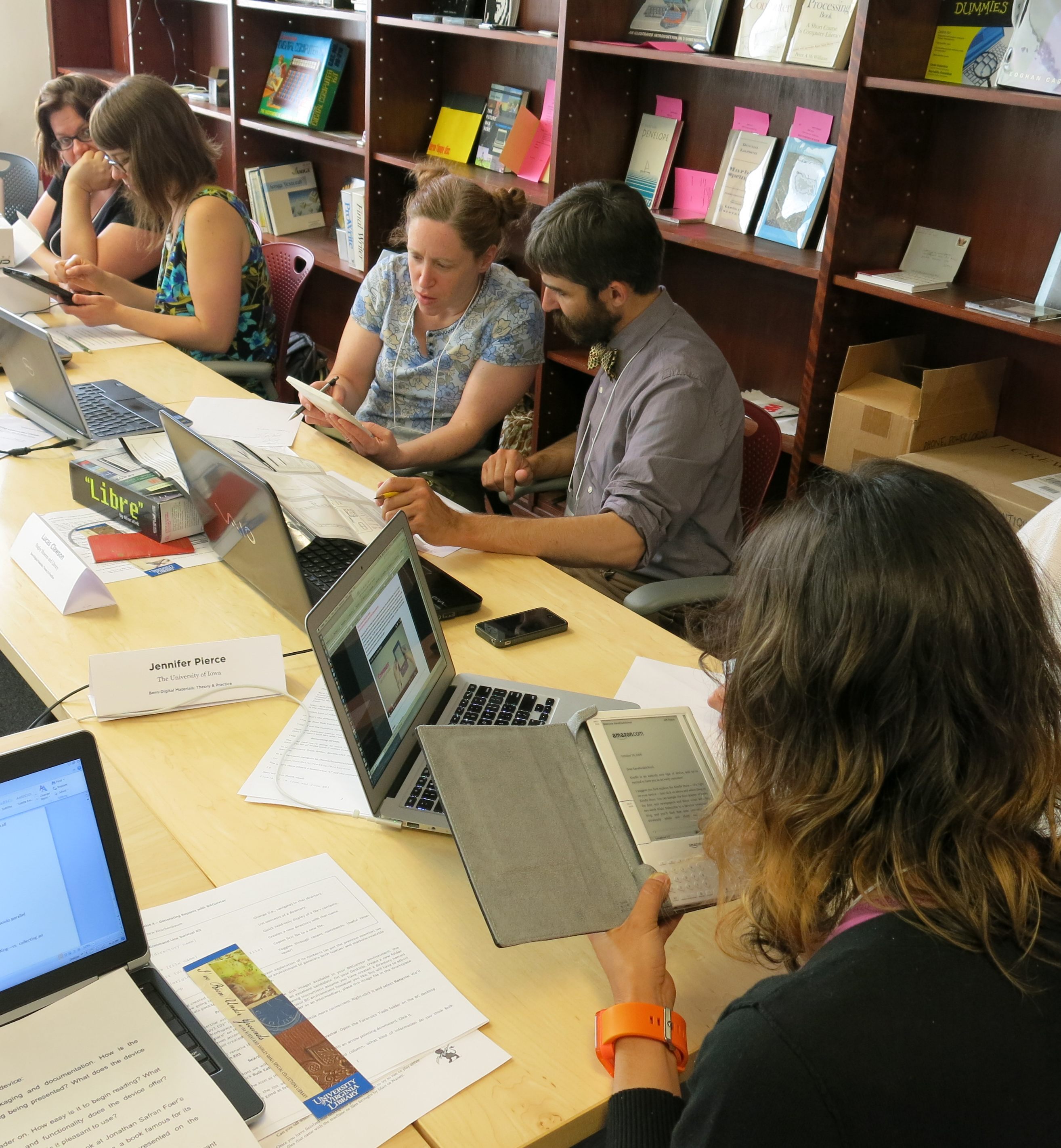

Students in “Born-Digital Materials: Theory & Practice” explore vintage e-readers from the RBS collections.

Among the school’s instructors is Naomi Nelson, who was the interim director of the Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University when Salman Rushdie’s archives were acquired. They arrived largely in the form of Apple computers. While it’s possible to see the physical changes an author such as Jane Austen made to a paper manuscript, modern authors can erase at will and save multiple drafts.

Oversized wood type from the RBS teaching collections.

Oversized wood type from the RBS teaching collections.

Digital technology has also opened up another, less appealing, conundrum for the rare book community: Forgery. Once considered a problem mostly for the art world, it seemed unlikely forgers would go through the trouble of constructing entire books.

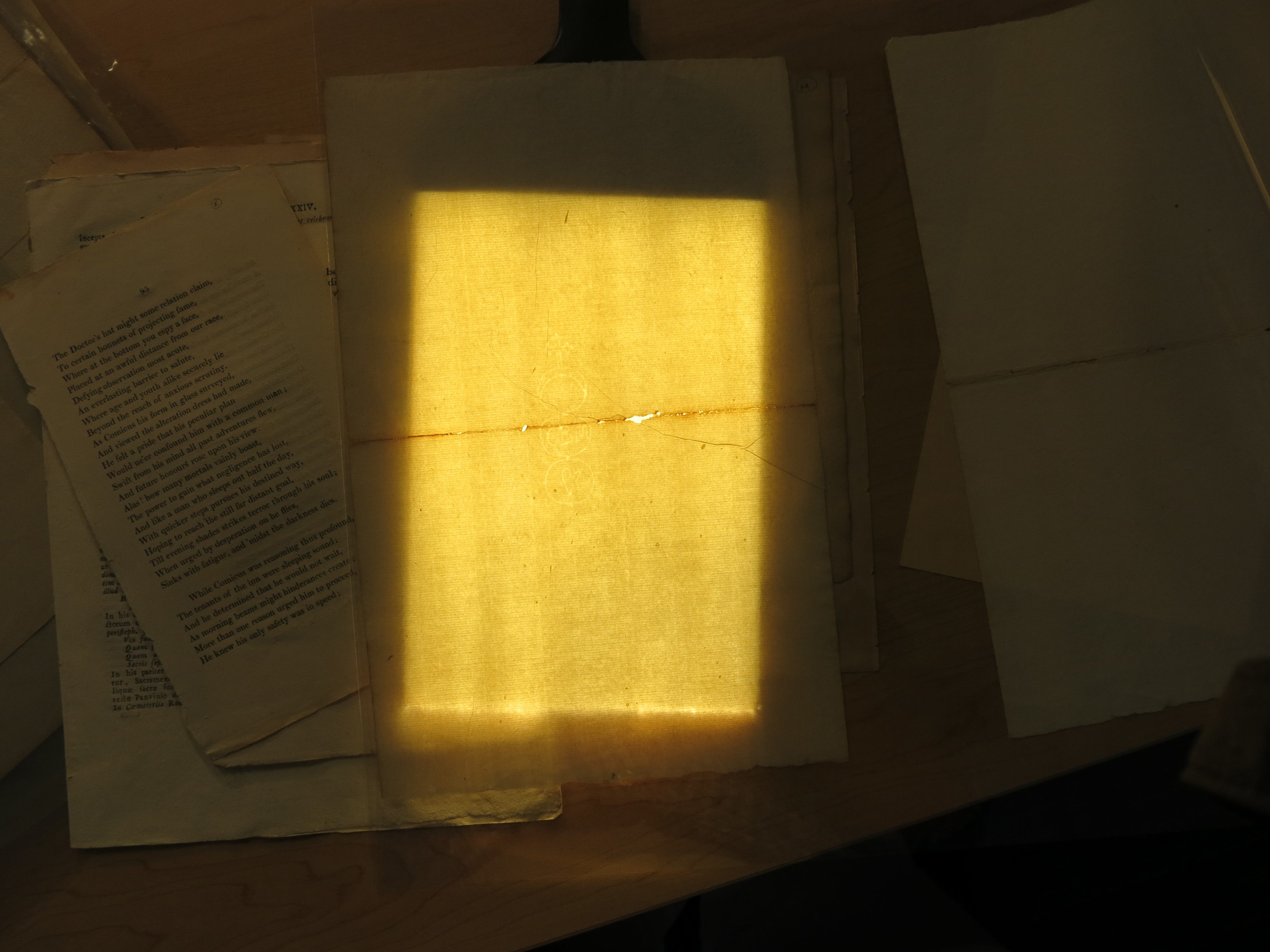

A watermark in handmade paper; as an exercise in “The History of European & American Papermaking,” students use reference works to identify and date such watermarks.

“Now it’s the case that you don’t have to actually set type to make a forgery,” says Dibell. “You can take a really good picture of a book and make a plate with it—a photopolymer plate—and then print from that.”

In 2005, an antiquarian book dealer purchased a copy of astronomer Galileo Galilei’s “Sidereus Nuncius” (or “Starry Messenger”) for half a million dollars. But the book wasn’t antique at all; it was fake. The book has since become an object of fascination for the rare book world. In 2014, two academics key to uncovering the fraud presented a talk to the school on what could be learned from the strange text.

RBS instructor Consuelo Dutschke (at right) and students in “Introduction to Paleography, 800–1500” examine a manuscript from the collections of the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

RBS instructor Consuelo Dutschke (at right) and students in “Introduction to Paleography, 800–1500” examine a manuscript from the collections of the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

But book nerds take note: Even as the school marches into the digital era, physical books still remain its core obsession.

“We have lots of people say at the end of every week, ‘I’m never going to look at books the same way again,’” says Dibbell. “Because you see what’s happened on the inside and what has gone into making that book. And you begin to see things in a totally different way.”

Early botanical prints are used to demonstrate illustration techniques in “The History of the Book, 200–2000”.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook