Revenge Zombies and Necropants: A Brief History of Icelandic Sorcery

Lick my face or I eat your brains. (Photo: Ben Sisto/Flickr)

From the ghoulish pants made of human flesh to the unsettling “tilberi”, an object made of a person’s rib that looks like a monstrous parasite, historic Iceland’s magical rituals are frankly a bit insane. But why? And where does Icelandic sorcery even come from? To find out, we spoke with Sigurður Atlason, Manager of the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft.

And that is how we learned the basics of creating an Icelandic revenge zombie.

Atlason, who goes by the nickname “Siggy,” is an expert on the history and performance of Icelandic sorcery. As Atlason explains, much of Iceland’s folkloric magical practices date back centuries, with roots in pagan ritual that dates back even further. Around 1000 CE, the population of Iceland was quite small, but in addition to the Nordic settlers who brought their pagan beliefs to the country with them, there were also a number of Christian settlers hailing from Ireland, Scotland, and elsewhere. Atlason says that in order to avoid a religious civil war, the country’s parliament decreed that Christianity would be the official religion, but the citizens would be allowed to practice their Nordic beliefs in private, and for themselves.

Through the centuries, the belief in what we now call magic and sorcery persisted. Arcane rituals and “hidden people” (or “elves”) became an important part of local folklore and tradition, seeping into the symbology and the names of landmarks all across the country. Some of it even mixed with the imposed Christian beliefs, creating a hybrid religion.

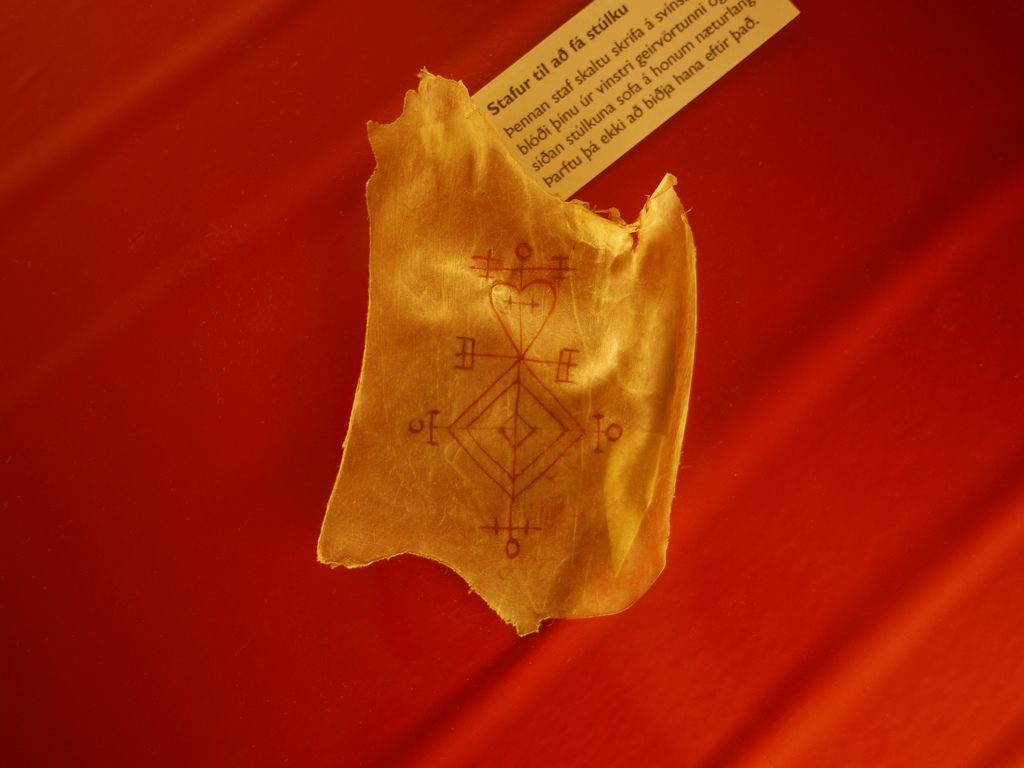

An Icelandic sigil drawn on what I hope isn’t skin. (Photo: Bernard McManus/Flickr)

This faith-filled potpourri persisted until until the 17th century, when the Christian reformation found its way to Iceland. The church decided to introduce the concept of “magic” as we know it today in order to marginalize the pagan practices. What was once the realm of traditional belief and historic folklore was now the work of sorcerers and witches. As they ever have, the ruling Christian church now had an excuse to bring the hammer down on Iceland’s pagan past. Men and women suspected of sorcery were burnt at the stake in witch hunts that inverted the common victims of superstitious persecution along gender lines. The beliefs of the old world were pushed from the daylight, but never quite extinguished.

Even today, this tension between pagan and Christian belief continues. Atlason references the installation of a guardian elf statue (elf culture is alive and well in modern day Iceland) at the mouth of a recently dug tunnel. Christian protesters still came out to lodge their complaints at the blasphemous magical creature.

Despite all of the conflict surrounding Icelandic magic in the 17th century, many of the rituals and invocations that evolved over centuries of hard living in the often inhospitable wilds of Iceland, still survive. There are the previously mentioned necropants, a magic pair of leggings made of the skin of a dead friend that would endlessly manifest riches after a coin stolen from a widow was place in the scrotum; and the summoning of the tilberi, which only a woman could perform by stealing a dead man’s rib, hiding it in her bosom, sneaking it meals of church wine, and wrapping it in grey sheep’s wool, after which the resulting double-headed worm creature would steal massive amounts of goat’s milk to make butter with. Atlason stressed that these rituals were obviously never truly performed, but acted more like folktales, giving the citizens of early Iceland the one thing magic truly created, which was hope.

Dear lord. Behold the tilberi. (Photo: Bernard McManus/Flickr)

We asked Atlason if there were any other elaborate rituals like the tilberi or the necropants, but he said that they are both quite unique in the pantheon of Icelandic magic. However then he told us about the process of raising a person from the dead.

In the country’s pagan beliefs the spirits of departed friends and relatives were apparently fairly common, but were not sources of malevolence, but raising a body from the dead was a whole other can of worms.

[In order to wake up a dead person] you have to shout out some poetry, some invocations, over the grave. And walk around the church graveyard. And spit on the grave. It can be quite nasty. It is the words or the language that [are] most important to get correct in order to get them up. And it’s very dangerous because of course, once you get the dead man up, he’s nine times stronger than he was in life. So you would never chose a very strong fisherman or farmer, you would choose a teenager or some guy who is not very strong.

You have to fight a little bit with him once he gets up. You have to manage to put your head in front of his and lick up all the liquid that streams out of his nose and mouth, and actually clean him with your own tongue. That’s how you tame him. After that you can just tell him whatever he has to do.

Once you send him on a person you dislike or is your enemy, [the zombie] is not only following him until his life is over, but he also follows the next seven generations. So it’s a big revenge.

In addition to these elaborate rituals and spells, there survive countless sigils and poetic invocations that Atlason says are filled with “swearing” (although it was not clear if this meant offensive words or devotional ones.) The goal of all these rituals, though, is shared: to create hope. All it takes is tongue-cleaning an angry zombie, or wearing a dead friend’s magic scrotum.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook