Long Before Peyton Manning Met Budweiser, the Pope Shilled For Cocaine Wine

Twinings tea producers, by Royal Appointment since 1837. (Photo: Ruth Hartnup/flickr)

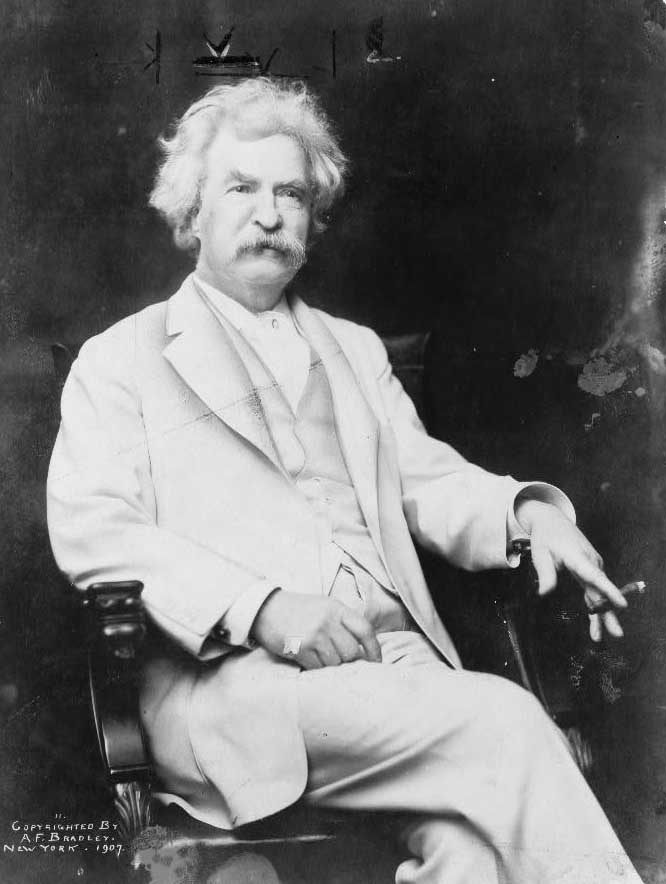

There is no reason Mark Twain should make you want to buy lemons.

A scan through the famed humorist’s work contains no big roles for lemons. He is from Missouri—not exactly lemon country. A cocktail named for him features lemon juice, but so do a lot of cocktails. And yet, in 1923, his likeness was used to advertise “Mark Twain” lemons and oranges from California. Then again, his image was also used to sell flour, cigars, fountain pens, Oldsmobiles, shirts and watches, both before and after his death.

As the plethora of Twain-branded goods shows, coherence doesn’t really matter when it comes to celebrity endorsements. The cache of a celebrity association overpowers anything else.

Mark Twain’s image was used to sell several products, including cigars. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Buyers know the basics of what they need and want, but rely on expert, or at least experienced, opinions when it comes to specifics. Does my dentist recommend this toothpaste? Does my hairdresser think this conditioner is working? Do other people who stayed at this hotel have good things to say about it? While a celebrity offers none of this, he or she does present a perceived expertise in taste. We want what they sell not because of who they are, but what they represent.

Before we had celebrities in the modern sense, we had royalty, and they are where the earliest versions of celebrity endorsements came from. In 1155, King Henry II issued the earliest recorded royal charter to the Weavers’ Company, a city livery company, which noted the trade guild provided loyal and reliable service. Charters could be used to establish cities, but when it came to goods and services, a royal charter denoted the product or company was favored by royalty. Later, that kind of referral was established by the Royal Warrant of Appointment. In 1684, the English palace had a “Haberdasher of Hats, a Watchmaker in Reversion, an Operator for the Teeth and a Gaffe-Club Maker,” all offering official services.

That didn’t mean much until the Industrial Revolution. Until then, the only people doing much buying were other royalty and nobility, and they likely already knew were who the favored tradesmen and guilds. But in Great Britain in the 18th century, agricultural innovation, increased movement to cities, and international trade all contributed to a middle class working for wages instead of subsistence farming. Wages meant they began to have buying power. They could accrue stuff.

Classic Wedgwood china. (Photo: Lionel Allorge/CC BY-SA 3.0 WikiCommons)

So begun the rise of brands reliant on celeb endorsements. Josiah Wedgwood, for instance, understood, that the new consumer class couldn’t afford imported tea sets from China, but still wanted quality. He also understood the hometown pride that could come from producing goods as fine as those from Asia in Great Britain. Wedgwood developed technologies for creating fine pottery, but also began advertising his goods. First, he targeted the nobility. In 1765 he created a tea set for Queen Charlotte, and received a royal endorsement. He then named his cream-colored porcelain “Queen’s Ware,” and continued to make other high-quality (yet mass-produced) products. By connecting Wedgwood products with the tastes of the landed gentry, the celebrities of the day, Wedgwood kicked up demand from the general public. He also raised prices for the elite in order to lower prices for the middle class, ensuring his goods stayed attainable without losing their reputation as luxury items.

Wedgwood was an early adapter of the concept of advertising, but by the 19th and 20th centuries, “What do I spend my money on?” was the question on the minds of most of the middle class. Instead of obtaining goods out of necessity, there was now some choice involved. It wasn’t about which goods were necessary, or the cheapest and most readily available. Consumers began to question what buying certain goods said about them. There was the potential for brand loyalty.

An advertisment for Mariani wine with the endorsement of Pope Leo XIII. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

“There is a lot of clutter in advertisements,” says Dr. Dipayan Biswas, Professor of Marketing at the University of South Florida, and the Editor of the Journal of Consumer Marketing. “Celebrities and other people that are known and liked by the masses automatically gets your attention.” But aside from getting you to notice the product, there is a certain sense of expertise a celebrity can convey. “When you have Eva Longoria selling makeup, she is considered beautiful, so if she advertises makeup you associate it with that outcome,” says Dr. Biswas. A celebrity is successful at being famous, and aspects of fame—whether it’s beauty, confidence, notoriety, or the whole thing—are what many of us aspire to have. Thus, whatever the celebrity uses must be in service of those goals.

Many early celebrity endorsements came not from advertisers, but from the celebrities themselves. For example, the Pope endorsing cocaine wine. In 1863 Angelo Mariani created a concoction made of French Bordeaux and coca leaves, advertised to restore health, give you energy, prevent the flu, and anything else miracle drugs are often thought to do. Pope Leo XIII was reportedly a fan, and appeared on a poster claiming he sent a medal to Mr. Mariani “as a token of his gratitude” for the product. In another poster featuring the Pope, consumers could write in to Vin Mariani and receive a book “containing portraits and endorsements of Emperors, Empress, Princes, Cardinals, Archbishops, and other distinguished personages.”

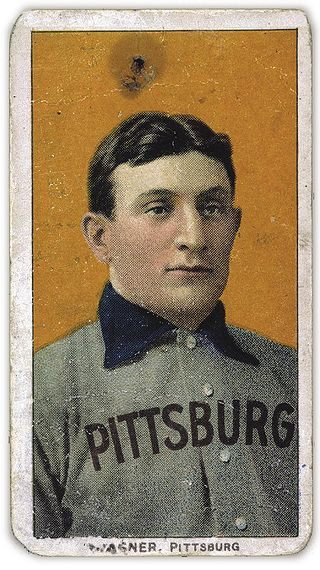

The T206 Honus Wagner baseball card, with the unauthorized use of Pittsburgh Pirates’ Honus Wagner. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The Pope seemed to be fine with his likeness being used in association with cocaine wine, but companies could (and still do) get in trouble for using a celebrity’s likeness without their permission. The earliest cards, produced by the American Tobacco Trust in 1909, featured the image of famous baseball players on one side and an ad for various brands of tobacco on the other, with the idea that consumers wanting to collect an entire set of cards would keep buying that brand of tobacco to do so. The most famous one today features Pittsburg Pirate Honus Wagner, because Wagner forced American Tobacco to stop production of the card. According to his granddaughter, it was because “he didn’t want kids to have to buy tobacco to get his card.” (Wagner did however lend his name to plenty of other products, including gum, razors, and Louisville Slugger baseball bats.)

There is risk involved, though, for both the celebrity and the brand. “If something bad happens to the celebrity it’s associated with the product,” says Dr. Biswas, and vice versa. In 1976, teen heartthrob Pat Boone (though by then a little past his prime) and his teenage daughters appeared in an ad for “Acne Statin” pimple cream, which the daughters claimed to use with great success. Boone received royalties based on sales of the cream. However, the ads claimed the product was a “cure” for acne, and when the FTC realized the brand was making false claims, they cracked down not only on the company, but on Boone. He signed an order to stop appearing in ads for the product, and to help reimburse customers. But no matter the risk, celebrity endorsement endures. Lemons just taste better with Mark Twain’s face on them.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook