The Many Possible Reasons British People Hire Chimney Sweeps for Their Weddings

Something old, something new, something borrowed, and a guy in a top hat covered in soot.

Kevin Giddings, 54, is the owner of Milborrow Chimney Sweeps in West Sussex, England. Despite some big name clients, including Buckingham Palace, his job is reasonably straightforward. Most days, he and his employees do house calls, which involve fixing fireplaces, cleaning boilers, and, of course, sweeping chimneys.

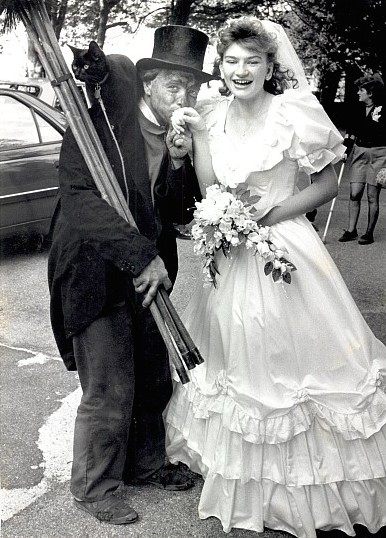

A few times a month, though, Giddings’s profession entails slightly different duties. On those days, he dresses up—in a top hat, black gloves, a cravat, and a dress jacket with tails (he puts the jacket on right over his boiler suit). He sits his black cat, Sooty, on his shoulder, and picks up an old-fashioned wooden chimney brush. He smears soot all over his face. And then, once he’s all kitted up, he heads off to a stranger’s wedding.

Everyone knows that a luck-seeking bride needs things old, new, borrowed, and blue. But in Britain, if you’re trying to tip the scales toward wedded bliss, you’d best make sure you also have a genuine chimney sweep. For a small fee, often around £100, you can ensure that one shows up to shake the groom’s hand, kiss the bride, take photos, and generally spread sooty cheer. “Our job is to wish good luck to everybody,” explains Giddings. “It’s one of the best parts of being a chimney sweep.”

“It’s thought to be lucky to have a sweep at your wedding,” explains Liz Leicester of Pete the Sweep in North Yorkshire, whose husband, Mark Leicester, makes such appearances. But as with most superstitions, the roots of this one are hard to trace. One common story, which Leicester and Giddings both told me, involves King George II, a puppy, and an errant horse.

Basically, they say, during a royal procession, a dog nipped at the legs of the king’s steed, and the horse spooked. A chimney sweep then appeared out of the crowd, brought the animal under control, and disappeared again. “The king wasn’t able to thank the sweep personally,” says Leicester. “So he said that from that day onward, sweeps should be regarded as lucky.”

There are other explanations, too. In a 1951 article for Folklore, the historian Philip Brown went through most of them, and didn’t come to very many conclusions. It could have something to do with the ancient Roman association between soot and fertility, he says—Vulcan, the god of fire and forge, was married to Venus, the goddess of love—or an old tradition of sweeping out the fireplace on New Year’s Day, for good luck.

Certain 17th century May Day parades may or may not have been preceded by street sweepers, who may or may not have dressed like chimney sweeps. There’s also another popular (and likely false) story, in which a chimney sweep falls off a roof, gets snagged on a gutter, is pulled through the window by a “young lass,” and marries her soon after.

There could be a moral dimension, of humbling oneself on a somewhat prideful day—a bride dressed all in white takes a risk by giving a sooty sweep a peck on the cheek. Giddings puts forth a purely utilitarian argument: “Two hundred years ago, when a new bride became a wife, she became the mistress of the household,” he says. “The mistress of the household had to be in charge of the cooking, the heating, the hot water… if she didn’t get to know the chimney sweep, she couldn’t look after all that.” In other words, better to start strong from day one.

If you look at real-life British history, luck and chimney-sweeping make somewhat strange bedfellows. Beginning in the late 1600s—after the Great Fire of London decimated many of the city’s old buildings, and people built new ones with skinnier chimneys—adult sweeps began hiring young boys, often orphans, to scuttle up inside of the chimneys to clean them.

The insides of chimneys aren’t very healthy places, and many of these so-called “Climbing Boys” ended up with burns, irritation, and respiratory diseases—or “Chimney Sweep’s Cancer,” a type of scrotal tumor that was the first occupational cancer ever diagnosed. Life was so bad for young sweeps that in 1864, Parliament passed a law banning the use of climbing boys.

The idea of the lucky chimney sweep survived this historical irony, though. “In the British Isle or on the Continent only a stomach-ulcered cynic… would not gladly welcome a chance meeting with a chimney-sweep,” wrote George L. Phillips in 1951 in the Journal of American Folklore.

Lucky chimney sweeps show up in literature from Mary Poppins (in which a grumpy Mr. Banks refuses to shake a sweep’s hand) to Ulysses (in which a minor character invokes “soot’s luck”). According to Time magazine, on the morning of his 1947 wedding to Queen Elizabeth, Prince Philip “popped out of Kensington Palace at 11 o’clock [and] shook hands with a chimney sweep.”

Sweeps today love to keep up the tradition. It makes for a solid side hustle in the summer, generally a slow time for sweeping: Leicester says they’ll do at least a wedding per week from about April through September, and at one point, Giddings estimates he was getting about 100 gigs every year.

Lots of British chimney sweeping companies advertise wedding appearances, and although most stick with the standard Victorian getup, many try to differentiate themselves from the pack by offering souvenirs or special extras—champagne, official certificates, bags of genuine soot. Some work with the wedding parties to make sure they appear “out of the blue”—a chance encounter, even a choreographed one, is considered to be the luckiest.

Mark Leicester travels to gigs on a flower-decked bicycle, sometimes with a historically accurate assistant: “If he’s got one available, he’ll take along [a little boy dressed as] an urchin,” says Liz. And Giddings has his black cat, which he trained from kittenhood to love crowds and to travel around on his shoulder. (Sooty is the latest in a long line: “Unfortunately, the cats are not lucky in themselves, because they keep crossing the busy road near us and getting run over,” Giddings says.)

Besides the cats, though, everyone else tends to come out ahead. Wedding parties generally give good reviews—the best is when families become repeat customers, and the sweeps can check up on the couples they once helped out, says Leicester. And the ones who fare the best are probably the sweeps themselves, who get in, get out, and get paid. “It’s a happy day,” Giddings says. “I’m lucky to join in.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook