Revisiting an Explorer’s Northwest Passage ‘Disappointment’ After Nearly 230 Years

The 18th-century fur trader Alexander Mackenzie thought he was a failure, but he was wrong. He was just too early.

My first sighting of Garry Island came through wind and rain.

It was the summer of 2016, and my paddle-partner Senny and I had been winding our way through the river delta labyrinth for five days, when finally, in the distance, a black mound rose slowly out of the horizon. Our pace was labored, reduced to a crawl. The north wind off the Beaufort Sea blew rain into our faces, and invisible silt bars suctioned at our canoe. The delta was widening, the gaps between land growing, and as the view opened, as river became ocean, there it was, out in the bay, the tallest island in any direction.

No wonder Alexander Mackenzie halted his expedition here, at Garry Island, I thought. It’s the last dry landmark before the North Pole.

In the summer of 1789, Alexander Mackenzie and his companions—five hired voyageurs and two of their wives, plus the great Chipewyan chief Awgeenah, with his wives and hunters—embarked in a flotilla of three canoes, launching from modern-day northern Alberta. Mackenzie was a fur trader in search of a water route to Asia, and he carried a speculative map that showed a river connecting the heartland of North America to the Pacific Ocean. If he was able to confirm this interior Northwest Passage, and develop a new trade route to China, Mackenzie would be a mercantilist hero and rich beyond his dreams.

Mackenzie’s expedition was the first recorded descent of the massive river that now bears his name. In order to write a new book on Mackenzie, I retraced his route down that river, the second largest in North America, paddling my own canoe 1,125 miles from Great Slave Lake to the Arctic.

For me, reaching the northern ocean would indicate success. And yet for Mackenzie, always a practical businessman, it meant nothing but frustration. Mackenzie died thinking his quest ended in failure. It turns out he was wrong, though, and for reasons he couldn’t have imagined at the time.

After 39 days of toil, Garry Island and the open sea finally came into sight, stark against a threatening gray sky. From the moment I looked at a topo map during my trip planning, it was this very last section that had given me pause. Paddling the inland river was daunting, for sure, but feasible in a straightforward way. These final few miles, though, had the potential for disaster. An open water crossing, out into the Arctic Ocean, in a canoe.

Rain forced us to shore, and we made a cold and hungry camp. The storm beating against the outer skin of the tent, I checked the weather forecast off the satellite. It was still there, as it had been all week: a three-hour window of calm seas predicted for the next morning, our best shot to cross to Garry Island. But as I lay huddled in my sleeping bag that night, I thought of the cautionary tale I heard from a man named Shawn Patterson, whom I had met two months before.

Patterson is the collections manager at Fort William in Thunder Bay, Ontario—he described the site as a sort-of Colonial Williamsburg for fur-trading history nerds—and a recognized Mackenzie expert. In 1989, he was on the official Canadian expedition recreating the bicentennial journey, so I asked Patterson for advice, about the trip generally, but especially the last bit to Garry Island.

“Oh, we didn’t get to Garry Island,” Patterson had told me.

“What do you mean?” I was incredulous. “How could you go all that way and just stop before the end?”

“The weather stopped us,” he said. “The hail was coming in sideways, and I looked out my tent flap and saw a red tail hawk completely motionless in the air, unable to fly against the wind. It was a mutual decision, we all agreed. We knew we couldn’t make it.”

The official Canadian bicentennial expedition didn’t reach Garry Island. What made me think I could?

Among Americans today, Alexander Mackenzie is all but forgotten. Even in Canada, he is a figure a little like Daniel Boone, a famous historical name though many would be hard-pressed to say exactly why.

The bicentennial voyage, of which Shawn Patterson took part, was more than an anniversary paddle. It was a full historic recreation, with period costumes and birchbark canoes, each role faithfully reprised. Patterson looks the part of an 18th-century voyageur—a beard and compact build help—and played Joseph Landry, the gouvernail, or rear steersman, for Mackenzie’s 25-foot canoe.

At community centers across Canada, Patterson and his crew stopped and set up small educational performances for school children. The actor playing Mackenzie would come out first in his big wool coat, and Patterson would ask, “Who is this?”

“The number one answer, every time, was Abraham Lincoln,” Patterson says, “Blond hair, no beard, but he had the big top hat. So we’d say, ‘No, look, he has his First Nations partners with him.’ And the kids would think, and then the second guess was always the same too. Lewis and Clark.”

Ironic, as it is actually Mackenzie who holds the distinction of leading the first recorded crossing of North America, not Lewis and Clark. In 1793, Mackenzie made a second attempt to cross the continent, over an extremely rugged section of modern-day British Columbia. He reached the Pacific north of Vancouver, and in so doing, beat Lewis and Clark by a dozen years. Mackenzie’s published memoir of the trip inspired Thomas Jefferson to send Lewis and Clark at all, and they carried a copy of the best-selling book in their canoe.

Alexander Mackenzie was born in 1762 in the small town of Stornoway, on the island of Lewis in far northern Scotland. His family emigrated to New York City in 1775, and became refugees during the American Revolution, fleeing to Montreal, where young Alexander apprenticed as an accounting clerk at a fur-trading firm. The business went like this: French voyageurs carried English guns, ammunition, wool, and rum up the Saint Lawrence and then fanned out across the pays d’en haut, the Upper Country, returning months later with thousands of beaver pelts bound for fashionable hat makers in Paris. From his book-keeper’s desk, Mackenzie saw fortunes made, as hardy traders pushed ever further into the vast northern wilderness; the longer and harsher the winter, the more luxurious the furs. Mackenzie was tough and smart, volunteered for “adventure,” as he would write in his journal, and was quickly promoted to run his own post in the boreal forest of America’s unclaimed inlands.

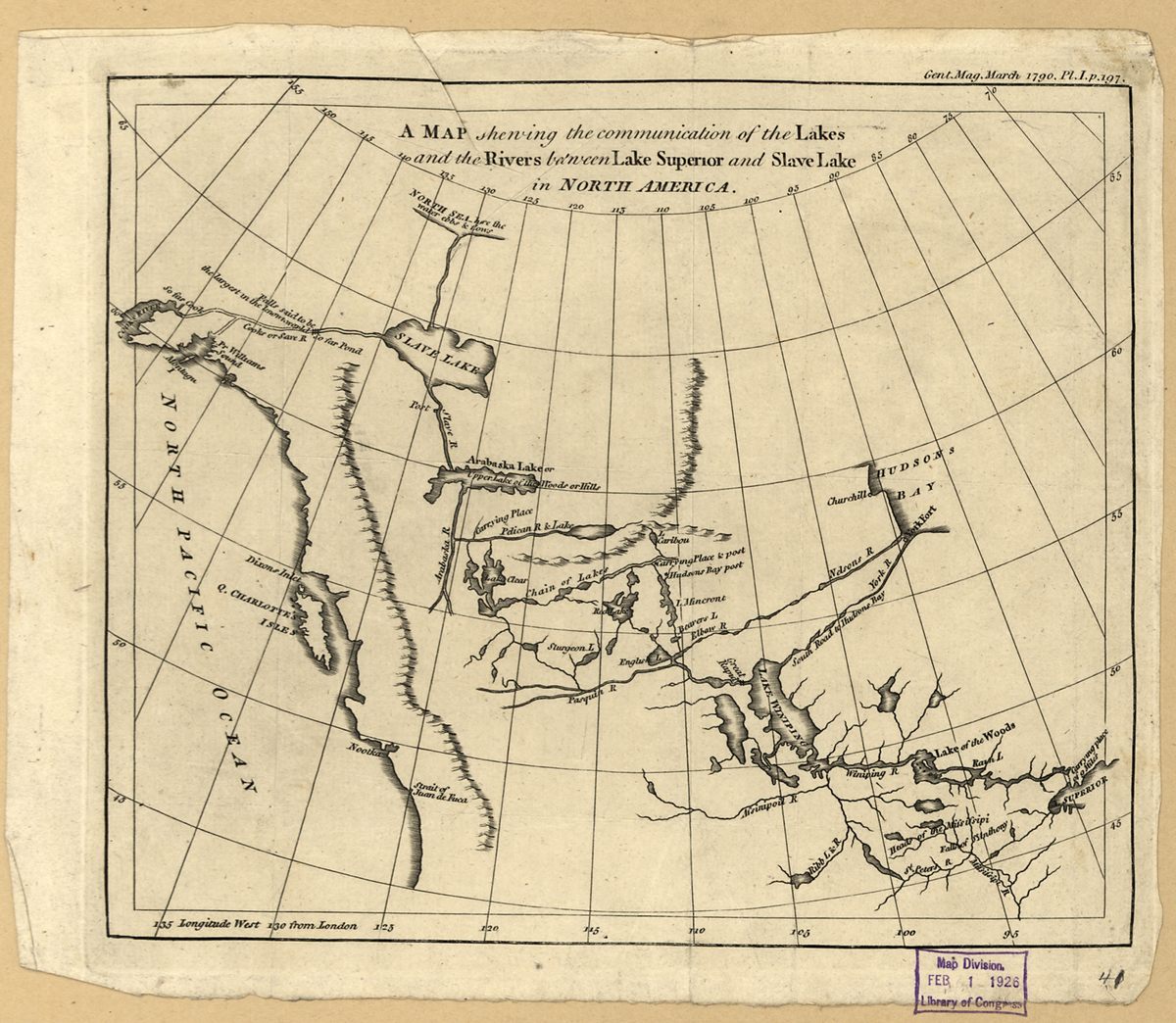

Honest maps of that time show a massive blank space in the northwest quadrant of North America. Very little had been explored by trained cartographers, and even less surveyed with any sort of accuracy. This map, from 1754, is typical:

Speculative geographers, an established and respected scientific class at the time, drew maps that filled in the gaps. Many sought to accommodate a Northwest Passage, a waterway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific. And so all manner of geographic features were invented. There was the Mer De l’Ouest, an inland sea of the western continent, and the Strait of Anian, which was drawn variously, sometimes separating North America from Asia, sometimes as a channel connecting Hudson’s Bay and the Pacific. Even as late as 1780, popular maps were full of the stuff:

That such a Northwest Passage should exist at all was considered a piece of inescapable logic. Since Aristotle, geographers subscribed to a philosophy of a balanced earth: that the same amount of land must appear in the northern hemisphere as the southern, that features present in one area would be mirrored in all others. This theory had already produced results. The long-sought terra australis, a large continent in the south required to balance Europe and Asia in the north, was found by Dutch sailors in the South Pacific in the 17th century; thus would Australia get its name. So too, if a southern passage existed around South America at Tierra del Fuego, naturally a corresponding waterway must exist in the north.

By the 1780s, sailors had probed all the crannies of Hudson’s Bay and the many straits around Greenland, and found every way blocked by ice. Thus, many geographers believed that the Northwest Passage must be a river through the continent, rather than a strait around it. One theory held that the Saint Lawrence River must be one end of this inland passage, and Cook’s Inlet at Alaska the other. Voyageurs and fur traders had uncovered the eastern portion of the route, from Quebec to Great Slave Lake, but it was up to Mackenzie to find the rest. This imagined waterway was called the River of the West, or sometimes the River Ouregan. And in 1787, Alexander Mackenzie met a man who thought he had found it.

Mackenzie spent that long winter with a haggard fur-trader named Peter Pond. While they were snowed-in together at a remote fort, Pond spun tales of a potential Northwest Passage. He was an amateur mapmaker, and constantly sought to fill the blank spaces in his own charts by quizzing his indigenous trading partners. One such chief, Awgeenah, told him an incredible story of a wide river that flowed into the setting sun.

Awgeenah often worked along Great Slave Lake, trading with the Yellowknife tribes that lived on the north shore. They told him that a mighty river flowed out of that lake to the west, directly to the sea. When Pond heard this, he drew a new map of the area. Captain James Cook had just surveyed the western coast of North America, and at the point where Anchorage, Alaska, now sits, reported a large inlet of unusually fresh water, choked with riverine driftwood. Pond put two and two together: Awgeenah’s river flowed to the Pacific, Cook had found its mouth. After centuries of searching and speculation, Pond believed the Northwest Passage was finally within reach.

By the time Mackenzie heard this story, Pond was past his prime, almost fifty years old. Mackenzie was the young up-and-comer. The North West Company, the Montreal business cabal that employed both men, picked Mackenzie to lead the expedition to verify the river’s route, and Awgeenah would act as his partner and translator.

English fur traders and French missionaries had been searching for this river for hundreds of years. The last best hope to find a Northwest Passage through North America lay in Mackenzie’s and Awgeenah’s expedition.

On June 3, 1789, the party of 13 left Lake Athabasca. They began at a latitude roughly equal to Stockholm, Sweden, and would ultimately travel hundreds of miles above the Arctic Circle. One hundred and two days later, they returned exhausted and so demoralized that Mackenzie would call his route “the River Disappointment.”

A combination of ice, fog, and tempest slowed their passage down the Slave River and across Great Slave Lake. For several days, the shore froze so tight they couldn’t break the boats through, and yet “our old Companions, the Muskettoes,” as Mackenzie wrote, tormented them in camp. Across the lake, thunderstorms lashed their canoes even as they dodged ice floes. A deep fog obscured their way, and they spent a full week searching bays for the mouth of the river.

Finally, on June 29, they detected current, and knew they were on the great river that Awgeenah had reported. For a while, it did go west and they made good time. But then the river hit the Rocky Mountains and made a hard right turn, at a place now known as the Camsell Bend. Mackenzie did not notice the severity of the turn, and mistook his direction and distance of travel for days afterwards. Storms kept him from taking noon-time navigational readings to determine his latitude, and his compass pulled easterly far more than he realized. Unknown to Mackenzie, magnetic north in Arctic Canada can deviate by as much as 45 degrees.

Mackenzie thought he was heading west, when in reality his travel was mostly north. He did not admit to himself, in his journal, that he was going the wrong way until the channel began to divide into the many-tined fork of a river delta. The weather broke, and finally able to use his sextant, Mackenzie discovered they were north of the Arctic Circle.

“I am much at a loss here how to act,” he wrote, “being certain that my going further in this Direction will not answer the Purpose of which the Voyage was intended, as it is evident these Waters must empty themselves into the Hyperborean Sea,” using the ancient Greek term for the Arctic Ocean.

Mackenzie surveyed his men, and they agreed that they might as well keep going. “I determined to go to the discharge of those Waters, as it would satisfy Peoples Curiosity tho’ not their Intentions.”

That night, the sky was finally clear after days of rain.

“I sat up last Night to observe at what time the Sun would set,” Mackenzie wrote, “but found that he did not set at all.”

On the maps, this great river is now labeled “Mackenzie,” though it had a name long before he arrived. The First Nations, the Dene and Gwitch’in and Inuvialuit, have used it as a highway for thousands of years. In their own languages, they all know it—as the Deh Cho, Nagwichoonjik, and Kuukpak, respectively—by a variation of this name: The Big River.

Based on my trip, I can corroborate that description. The fundamental emptiness of its broad valley smothers comprehension, a perpetual funnel of cliffs and black spruce marred by only the occasional traces of humans. In some places, it takes an hour to paddle across the river. In others, you can’t see the other side at all.

The night before our crossing to Garry Island, we were too cold and wet to cook so we crawled right in our bags, our only dry piece of gear. I wore every layer of clothing I had and still barely slept, shivering until our window of clearer weather and calmer seas arrived the next day.

In the morning, a dry gray sky spoke hope. But it started drizzling as soon as we pushed off, and then a wave front hit, surprising in the low wind; an ugly disorganized chop left over from the storm the night before, I figured. We trusted the surf would fade per the weather report, and so began the crossing.

I thought of Mackenzie and Patterson and their armadas of birchbark canoes. The challenge of reaching Garry Island had not changed significantly in 230 years. True, we had a fancy GPS and life vests, but also a much smaller boat and were all by ourselves, and in that moment, I felt both acutely.

After deciding to continue, Mackenzie directed his voyageurs to “the most Western land,” the place now known as Garry Island, that he approximated to be 15 miles away. I knew it to be only five miles, but as we got out into the bay, the north wind grew until it was screaming in my ears. The whitecaps came in at 45 degrees, as I angled the nose of the canoe so they couldn’t snatch our gunnel, and the rain began to stick, like sleet. The weather report proved wrong at exactly the wrong moment, and we didn’t speak a single word on the crossing, not a peep, until almost an hour later, when we made it to the far shore.

We ground the canoe on a gravel beach. “From here we could see the Lake covered with Ice at about 2 Leagues distance and no land ahead, so that we stopped….at the limits of our Travels,” Mackenzie wrote. The island stretched on and on in a wedge, a carpet of orange moss and pale green lichen, small bushes that dug themselves holes to escape the wind. “I went with [Awgeenah] to the highest part of the Island,” Mackenzie wrote, and we followed their route up the hill, to get a better view of the ocean. The whole thing smelled unexpectedly rich and earthy, as we balanced on unsure footing, tussock to tussock.

“We could see the Ice in a whole Body extending from S.W. by Compass to the Eastward as far as we could see,” Mackenzie wrote, and despaired. There would be no trip to China, no opening of trade, no fortune to be found or hero’s welcome upon return. I attained the same ridge, and looked out, my face to the north wind, and saw open water. Not a sliver of ice anywhere. Mackenzie thought he was a failure, but he was wrong. He was just too early.

Today, we think of the Northwest Passage as the commercial shipping route through the islands off the coast of Arctic Canada. But two hundred years after Mackenzie’s trip, climate change has now opened his passage as well.

Travel support for this story was provided by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook