Can We Blame the Mafia on Lemons?

Economists and historians are connecting the early rise of organized crime with Sicily’s citrus trade.

When Gaspare Galati took over management of the Fondo Riella in 1872, he knew he was in for a headache. The ten-acre lemon and tangerine farm just outside of Palermo should have been a prime piece of property, bringing its owner a slice of the booming citrus market that had northwest Sicily overflowing with wealth. Instead, it seemed cursed. Galati’s late brother-in-law, who had left him charge of the farm, had died of a heart attack after receiving a series of mysterious, threatening letters. And everyone knew that the farm’s warden, Benedetto Carollo, had been stealing more than his share of the profits for years.

Galati was a surgeon and a family man, well-respected by everyone in town, so he went by the book. First, he tried to lease the property—but Carollo made it impossible, harassing potential tenants and tanking the farm’s reputation by stealing pre-sold lemons off the trees. Eventually, Galati figured he’d nip the problem in the bud: he fired Carollo.

He must have thought that would be the end of it. Instead, in July of 1874, his new warden—Carollo’s replacement—was found lying between two rows of lemon trees, with multiple bullets in his back. After Galati hired yet another warden, more threatening letters began pouring in, accusing him of firing a “man of honor” in favor of an “abject spy.” If Galati didn’t re-hire Carollo, one missive said, he, too, would suffer the fate of his late warden—but “more barbarous.” In other words, someone was making him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

The local police were suspiciously resistant to arresting Carollo, and the local judges were loathe to convict him. Galati spent the next year figuring out how deep this thing went. Eventually, having seen too much, he was forced to flee to Naples with his family. He’d accidentally gotten himself entangled with a nascent crime ring that would soon be known far and wide: the Sicilian Mafia. And all it took was inheriting a lemon grove.

For decades, from mid-19th century through the mid-20th, if you were growing citrus in northwest Sicily—lemons especially—you were almost certainly dealing with the Mafia. As Helena Attlee writes in her history of Italian citrus, The Land Where Lemons Grow, “the speculation, extortion, intimidation, and protection rackets that characterize Mafia activity were first practiced and perfected in the mid-19th century among the citrus gardens of [Palermo].” In fact, the association was so strong that some historians and political economists now think the group actually arose directly from the citrus trade: life gave them lemons, and they made organized crime.

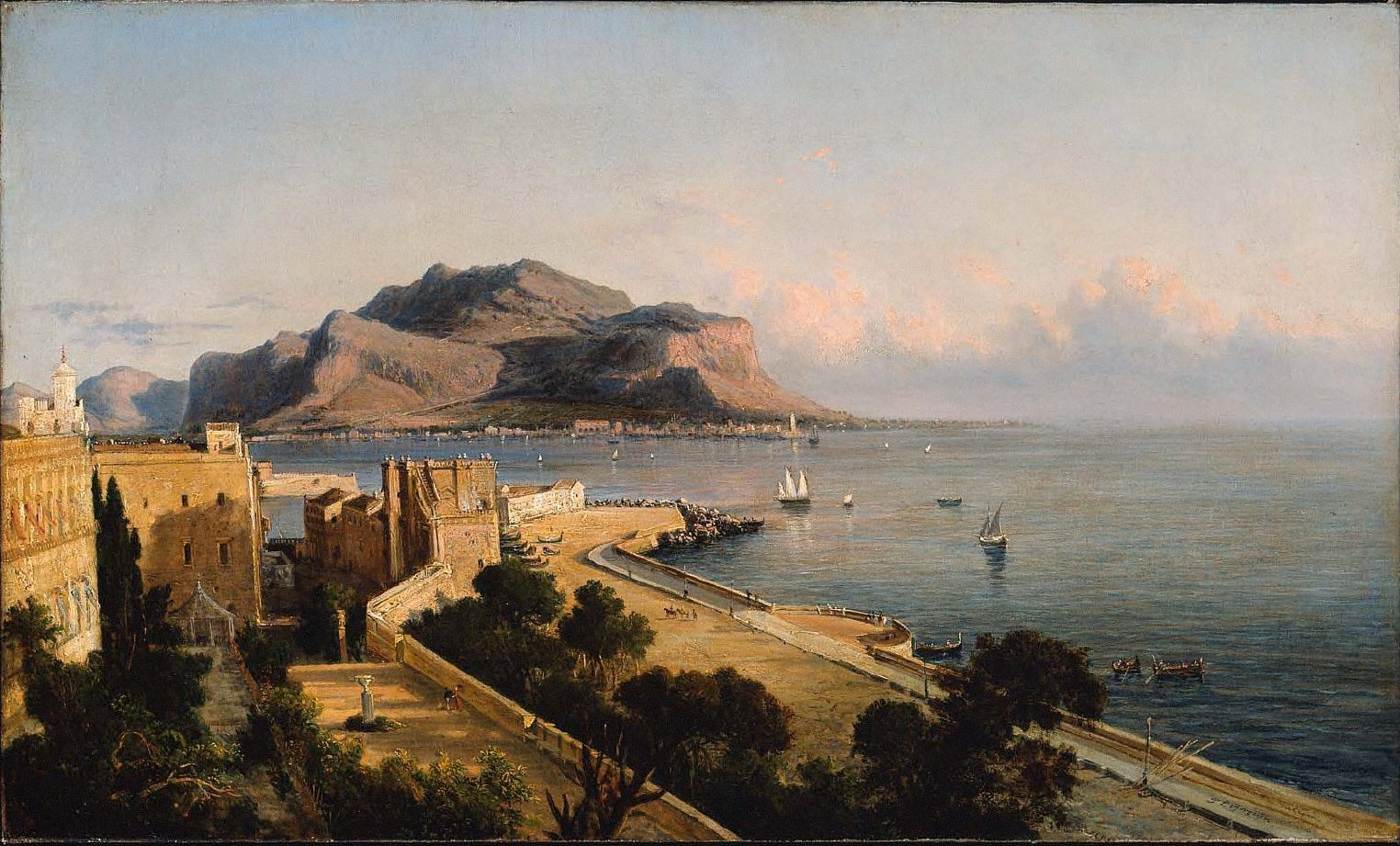

Citrus fruits have grown in Sicily since the 11th century, when Arabic conquerers brought bitter orange trees to the island from North Africa. The trees flourished, and more and more citrus species were shipped over. By the 15th century, the prevalence of the sun-soaked trees brought the bay around Palermo a new nickname. People began calling it the “Conca D’Oro,” or the “Shell of Gold.”

At first, lemons were essentially a luxury good—aristocratic landowners would grow them on their property, and either sell them whole as decorations or distill their peels into fragrant essences. Then, near the end of the 18th century, the British navy finally came around to the idea, presented to them decades before by the surgeon James Lind, that regular doses of lemon juice could fend off scurvy. The once-fancy fruits became a sudden necessity, and Britain began importing hundreds of thousands of gallons of juice from Sicily every year.

By the early 1800s, in the words of one historian, the island was essentially “a vast lemon juice factory.” The next few decades kickstarted a worldwide love for Palermo citrus, and ships began setting out daily during harvesting season, many of them headed to produce markets in Europe and the United States.

Around the same time, political turmoil led to a reorganization of land ownership in Palermo. As one group of researchers explains in a recent paper in the Journal of Economic History, early 19th century Italian lemon farming happened largely under a feudal system, in which peasants did the farming and the absentee landowners took most of the profits. A class of middlemen, called the gabellotti, managed these relationships, hiring workers and overseeing day-to-day work on the farm. Starting around 1812, popular revolts turned much of the land over to the gabellotti, who, fearing thieves and marauders, began hiring private guards to protect the assets that were now theirs.

Then, after 1860, when Sicily officially became part of Italy, parcels of what had been church- and state-owned land went up for sale. This led to a proliferation of small farms, and many of these new landowners also decided to grow lemons, by far the most profitable crop. They, too, found themselves in the position of having to hire guards—and those who couldn’t afford to do so found themselves targeted not only by thieves, but by the gabellotti and their guards, who saw a unique opportunity for extortion.

“The coalition between gabellotti, [guards], and [thieves] triggered a system of corruption and intimidation such that landowners who could not afford to hire a guard became the target of brigands,” the economists write. “This adverse institutional environment provided the breeding ground for the organization which would become known as the mafia.”

In the paper, they present some empirical proof for this claim—after studying a large-scale crime survey from 1886 and a map of mob activity from 1900, they found that the probability of Mafia presence in a given area of Sicily relates strongly to that area’s level of citrus production. Although other researchers have linked the birth of organized crime to different local resource booms, including the rise of sulfur mines, “we believe our paper complements [this research], and is able to explain some aspects that previous theories were not able to explain,” writes one of the authors, Alessia Isopi, in an email.

What made the lemon farmers such ripe targets? According to Attlee, much of the blame can be placed on the fruits themselves. “Among species of citrus in Italy, lemons are some of the most difficult and demanding to cultivate,” she says. They need well-fertilized soil, a steady supply of water, and protection from wind and extreme temperatures, all of which come only at great infrastructural cost. Most trees need to be coddled for seven or eight years before they produce enough lemons to sell. When they do bear fruit, it’s easy enough for people to steal it, especially when compared with smaller crops like wheat or olives.

The magnitude of such an investment, combined with the many possibilities for failure, made farmers “very vulnerable,” Attlee says. “They were just ready to be exploited by the first mafiosi.”

Over the decades, this exploitation became more and more sophisticated. It generally occurred in a kind of push-and-pull format that will be familiar to viewers of contemporary crime shows. If another farmer couldn’t afford to pump in water, a mafioso would gladly help him—and then make the farmer sign a contract that allowed him to charge massive amounts for that water, which he would do as soon as rainfall was low. As Galati’s experiences illustrate, they formed relationships with those who might have checked their power, especially policemen and judges.

The Mafia also controlled the trade itself, often buying a farm’s fruits to resell before they were even off the trees, and creating artificial shortages by picking green lemons and storing them until the prices improved. As Attlee writes, they had a sinister signal to show off their relationship with a particular grove: they’d nail a single lemon to one of the garden’s doors, and hang a shotgun cartridge next to it.

In more recent decades, Sicily’s citrus monopoly has loosened. New trade laws and shifting import taxes have made the once-golden crop much less profitable. The groves’ narrow rows and terraces—the very aspects that allowed the mafiosi to sneakily gun down, say, wardens they didn’t like—leave no room for large machinery, and have prevented farmers from achieving the industrial-scale production that is now common in places such as Brazil. By now, “there’s really not enough money involved in citrus to interest the Mafia,” says Attlee. They’ve moved on to juicier rackets.

But next time you squeeze a lemon into your tea, take a moment to pay it some respect—it’s a fruit with a bloody history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook