Man-Made Animal Crossings, from Bat Bridges to Toad Tunnels

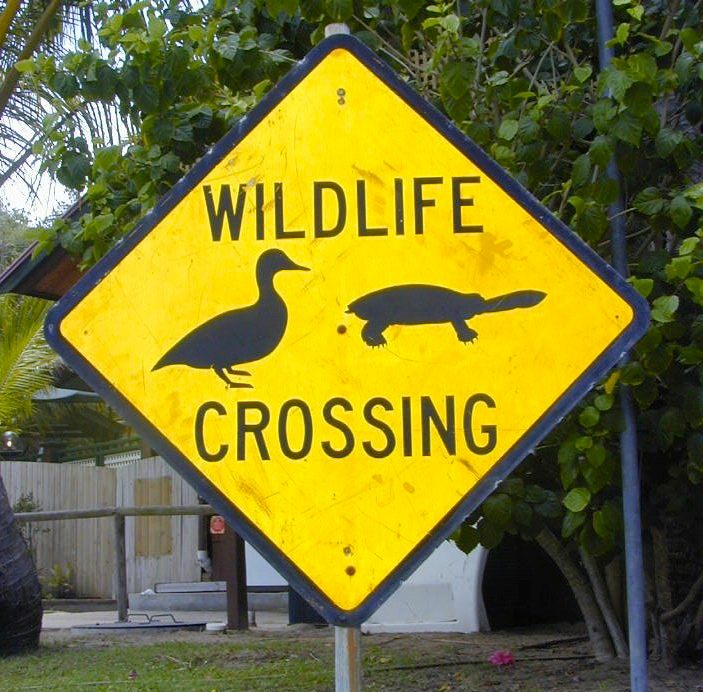

Look out. (Photo: Dennis Desmond/Wikipedia)

Look out. (Photo: Dennis Desmond/Wikipedia)

Unfortunately for makers of gifs and memes, animals can’t drive. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have their own highways.

Roads, of course, pose dire threats to both man and beast as they cut through the natural world—and not just common roadkill victims like deer and squirrels. The hazards to wild animals posed by speeding cars (and vice versa), has become a serious problem in some places and an increasingly popular solution is to fight fire with fire. To keep wild animals off of our roads, many problem areas have begun building them their own.

Collectively, these eco-friendly thoroughfares are known as “wildlife crossings” or “ecoducts,” although their design and construction differ a great deal depending on what type of animal the builders are trying to keep off the streets.

Possibly the most common variety of wildlife crossing is the animal bridge, found all over the world, with most of them in North America and Europe and some in places like Kenya where they allow elephants to pass under roads. These highway overpasses (and underpasses) look very much like the same overpasses that humans might drive or walk over, except they are covered in foliage and ground cover so that they appear to be just another portion of the landscape. These kinds of regreened bridges cater to all sorts of animals, especially larger beasts like deer, bears, elk, moose, wolves, and all other woodland creatures that would rather not play chicken (pun intended).

The animals are none the wiser. (Photo: Doug Kerr/Wikipedia)

Famously, Canada’s Banff National Park installed 24 wildlife crossings over portions of the Trans-Canada Highway, a busy four-lane blacktop that runs through the park. The 22 overpasses and two underpasses were built in 1978, and by the 2000s they were being used by at least 10 different species who were estimated to have cumulatively crossed the road around 84,000 times.

The Netherlands also created a successful system of woodland highways to save the dwindling population of European badgers. This expansive network of overpasses, underpasses, and ecoduct tunnels is comprised of over 6,000 crossings that have managed to end up saving not only the badger, but other species such as boar and deer who started using the badger paths.

The Netherlands is also home to the Natuurbrug Zanderij Crailoo, the largest wildlife crossing in the world. Completed in 2006, the ultra-long animal road extends over 2,600 feet over a river, roads, rail lines, and even a golf course.

Toad tunnel entrance. (Photo: Phoenix Hacker/Wikipedia)

Toad tunnel entrance. (Photo: Phoenix Hacker/Wikipedia)

And it’s not just the big animals that are getting their own Routes 66. Smaller tunnels, often referred to as ecoducts, are often built under roads to cater to all the critters that skitter, squirm, and crawl. A prime example of this type of creature crossing is the Davis, California Toad Tunnel. This amphibian alley was built in 1995 to keep the local frogs from getting squashed on a newly built overpass.

At first the six-inch-wide ecoduct didn’t seem to attract many frogs so lights were installed in the tunnels, but these were said to have heated the frogs to death. Despite this setback, the frogs eventually did begin to use the little road, however this simply provided the local birds with the equivalent of a frog vending machine. Eventually the Davis postmaster built a group of small buildings around one end of the tunnel, and named the settlement Toad Hollow. Today it is a regularly trafficked animal thoroughfare.

An English bat bridge. (Photo: MikeCalder/Wikipedia)

Most wildlife crossings are built to provide a path for a specific species, but end up getting co-opted by whatever other animals are just passing through. But there are other, more exotic wildlife crossings as well that cater very specifically to certain animals. There are squirrel bridges, like the Nutty Narrows Bridge in Washington, which are usually thin rope spans built to allow small woodland critters to cross busy roads; fish often need tiered ladders to help them swim up and around man-made barriers like dams, as is the case at Fish Ladder Park in Grand Rapids, Michigan; even airborne bats need a little help crossing busy roads and avoiding speeding cars, so bat bridges have begun popping up all over Europe in the form of nets and wires that are said to keep the bats from flying too low, strung high above busy roads. The efficacy of this last one is spurious at best.

Just like human roads, wildlife crossings provide a safe and orderly way for our animal friends to get where they need to go. And just like our highways all we can do is build them and wait to see how much traffic they get.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook