Touring the Abandoned Atlantic City Sites That Inspired the Monopoly Board

The once-glamorous casinos and hotels have become a gilded ghost town.

Boardwalk. St. Charles Place. Atlantic Avenue. If you grew up playing Monopoly, you’ll be familiar with these place names. While they may sound like they’re from a generic U.S. city, dreamt up by the game’s inventor, they exist in real life—in Atlantic City, New Jersey. But they are no longer what they once were.

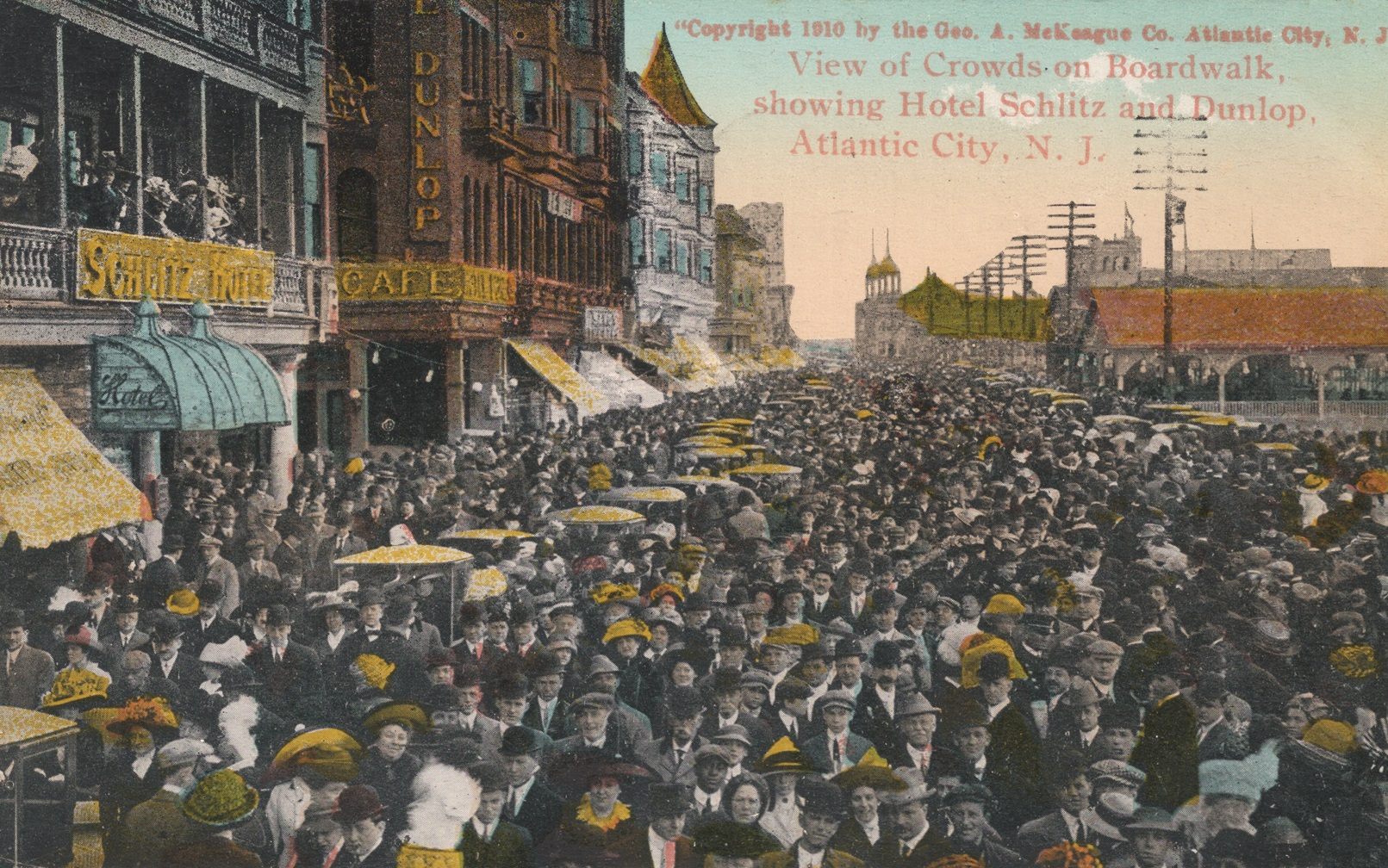

Today Atlantic City has a reputation as a destination for coach-loads of seniors looking to spend a day at the slots. But when Parker Brothers first produced Monopoly in 1935 it was one of the most luxurious and famous resorts in America. Grand hotels, saloons, dance halls and theaters stretched along the Atlantic Ocean for seven miles. The casinos were still 40 years away, but cocktails flowed for over half-a-million pleasure-seekers every year.

Part of Atlantic City’s appeal was in being open to everyone; from the well-heeled promenading down the Million Dollar Pier, lit by Thomas Edison, to the bawdier pubs and bordellos along the backstreets. “Businessmen learned quickly,” wrote Nelson Johnson in Boardwalk Empire, “working-class tourists had money to spend, too. What they lacked in sophistication they made up for in numbers.”

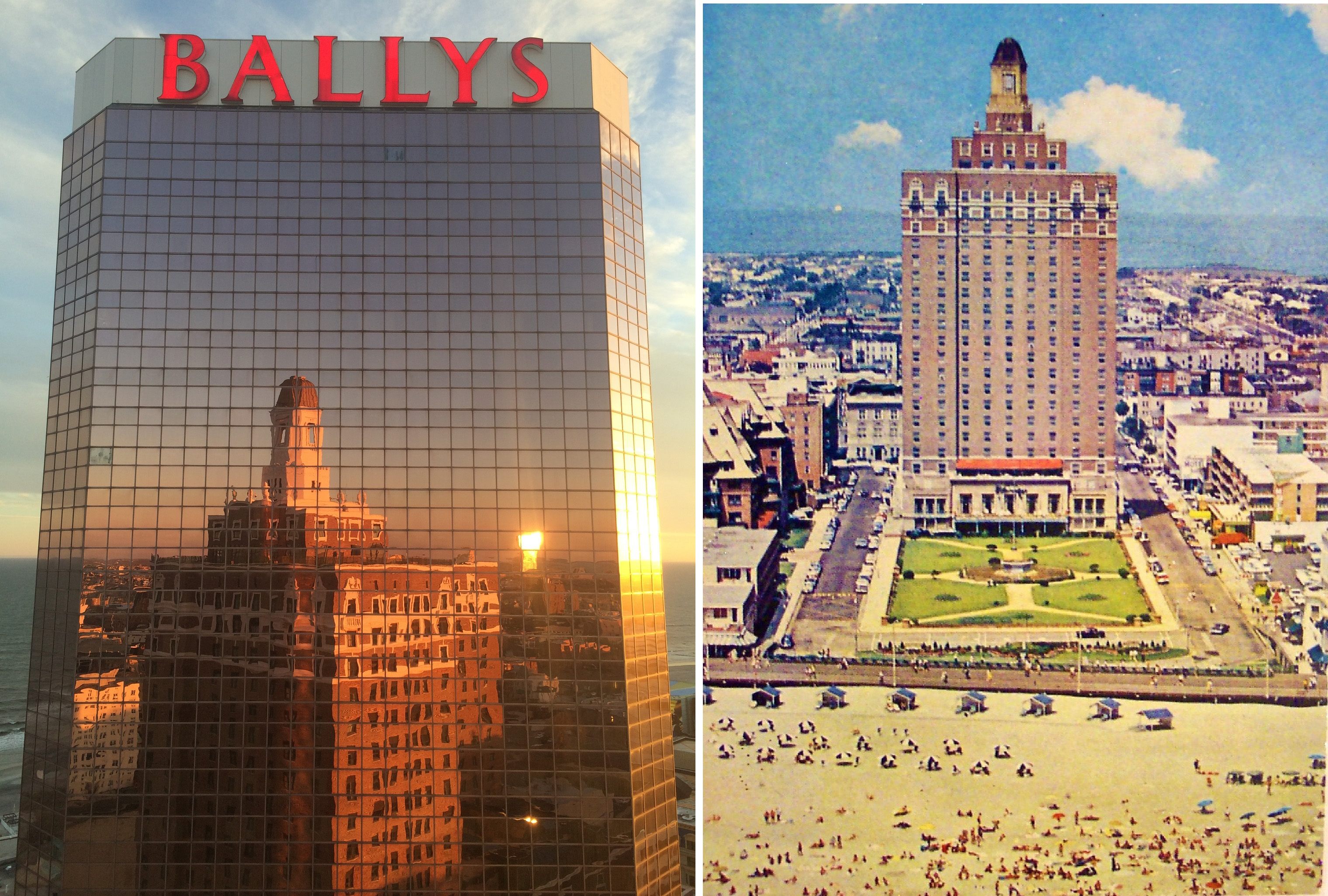

One of the last traces of old Atlantic City is the Claridge Hotel. Found on the corner of the two most expensive properties on the Monopoly board—Park Place and Boardwalk—the Claridge was known in its heyday as the “skyscraper by the sea.” Opened in 1930, it had an Art Deco opulence that wouldn’t be out of place in midtown Manhattan.

Stepping outside though, you are very quickly confronted with the grim air of the new Atlantic City.

Running alongside the hotel is Indiana Avenue, one of the highly desirable “reds” in Monopoly. It was once home to the iconic Sands Casino, whose Copa Room had been graced by Frank Sinatra. Bankrupt and demolished in 2006, it was repurposed into Artlantic, a public art project hoping to revitalize the beachfront after Hurricane Sandy. The project failed, and, like much of Atlantic City, was torn down.

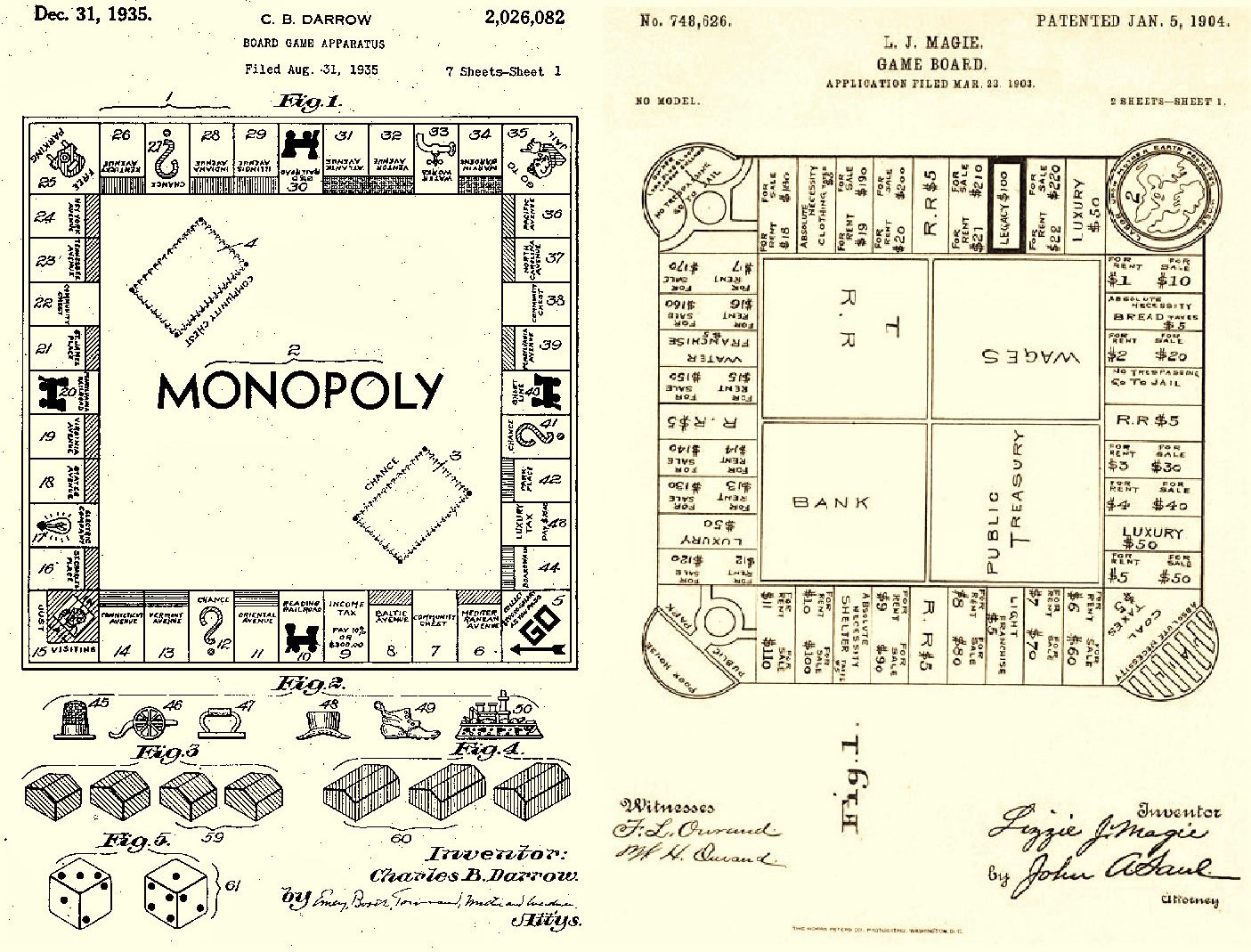

When playing Monopoly, there’s nothing quite as pleasurable as having your opponent land on one of your properties filled with houses or hotels, then squeezing them ever closer to bankruptcy while watching your cash roll in. According to Parker Brothers, Monopoly was created by Charles Darrow, a heating engineer from Pennsylvania, put out of work by the Great Depression. “It was the game’s exciting promise of fame and fortune,” the rules explain, “that initially prompted Darrow to produce this game.”

But that doesn’t tell the whole story of Monopoly; for the game was actually invented a generation before, by a woman. Elizabeth Magie worked as a stenographer, writer and actress. At the age of 37 she came up with the idea for a board game that would show the dangers of greed and economic privilege of monopolists like John D. Rockefeller through the entertaining medium of a parlor game. In 1903 she filed the patent for “The Landlord’s Game” based upon Henry George’s book Progress and Poverty.

It might have been forgotten altogether except for a dinner party held in Philadelphia in 1932. After dessert, the Landlord’s Game was brought out. One of the guests, Charles Darrow, asked for a copy of the rules as he left, and he produced his own version, which included Atlantic City street names.

Off-seasons in most seaside resorts are subdued, but Atlantic City holds an especially sombre feel, a garishly decorated ghost town, where many of the grand casinos are empty, bankrupt and abandoned.

Atlantic City has been through this before; following World War II, automobiles and cheap airfares drew away the holiday makers who once packed the trains from New York and Philadelphia, but now summered in destinations slightly more exotic than New Jersey.

Grand old hotels like the Marlborough-Blenheim on Park Place, which had been inspired by ancestral palace of the Duke of Marlborough, and the exclusive Traymore on Illinois Avenue—a hotel so opulent it was capped in gold—fell empty. As Atlantic City turned barren and boarded up, the city tried to reinvent itself, and turned to casinos.

In 1976, the Resort Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue (green on the Monopoly board) was transformed into the first legal U.S. casino outside of Nevada. Over the next two decades, gamblers flocked to Atlantic City as glitzy new high-rise casino resorts jostled for space along the Boardwalk. One local resident told NPR, “one of my fondest memories is … standing on the Boardwalk while people lined up to get in the casino. Ten o’clock in the morning, security guards open the door and these people, with their coin cuffs and change, ran—ran—to the slot machines.”

These vast, billion-dollar, behemoths offered every pleasure imaginable. And none were as spectacular as Donald Trump’s Taj Mahal. Today it sits empty on S. Virginia Avenue (pink), the latest of the grand casinos to fail. As gaudy as it was luxurious, with 72 gold minarets and nine elephants, it opened in 1990 at a cost of $1 billion, with Michael Jackson as the star guest. Trump boasted that its gambling floor, the world’s largest, was the “eighth wonder of the world.” Even though Trump sold his ownership in 2009, the enormous, towering Taj Mahal still bears his name.

By the time the Taj opened, cash-rich Atlantic City was dominated by Trump. At one point his casinos were generating a third of all gambling money in the city.

This was the second golden age of Atlantic City, an era when Mike Tyson held all his fights here, when gambling money flowed into the casinos. But for some, the warning signs were already there. One market analyst, Marvin Roffman, compared the city to a house of cards. As newer casinos sprouted up in Connecticut, New York and Pennsylvania, the crowds left Atlantic City. Crippled with debt, Roffman told the Wall Street Journal that the Taj Mahal alone needed $1.3 million a day just to survive.

One by one, the hulking casino hotels along the shoreline began to fold. The Playboy was the first to go in 1989, consumed by Trump’s World’s Fair, which itself failed a decade later. Trump Plaza, where high roller Akio Kashiwagi once lost $10 million in one of the most famous games of baccarat ever played, closed in 2014. Three other casinos closed the same year, devastating Atlantic City’s economy. The Taj Mahal finally closed in October 2016. Today it sits silent and forlorn, a golden folly on the seashore. Even though it’s been abandoned for a matter of mere months, the gilded paint is already beginning to peel.

As the casinos struggled, so did Atlantic City. Over a third of the 40,000 residents now live below the poverty line. On Pacific Avenue (yellow), prime real estate on the Monopoly board, vacant lots and boarded-up homes provide a desolate backdrop for one of the most violent cities in New Jersey, where five of the last nine mayors have been found guilty of some form of corruption.

At the far end of the deserted boardwalk are the light-blue streets of Oriental and Vermont Avenues. Here sits one of the most astonishing projects built on the east coast, the 52-story Revel. The casino hotel was built for over $2 billion in 2012, completely covered in blinding mirrored glass and chrome. The Revel was to be the great hope for Atlantic City. But within two years it was bankrupt and closed.

In the shadow of this gleaming mirrored empty monolith are a few, surviving old wooden row homes, belonging to those who refused to move. Nowhere is the difference starker between old and new Atlantic City than a walk along Oriental Avenue.

As desperate as the situation in Atlantic City seems, there are some green shoots of recovery. Caesar’s Palace, Bally’s and the Tropicana are still open on the Boardwalk, and the Borgata is the model of a successfully run, high-end casino, located a few miles northwest.

At the far end of the Boardwalk is one of the last traces of the Atlantic City of Boardwalk Empire. The venerable Knife and Fork seafood restaurant, which opened in 1912, still thrives with locals. When Monopoly came out, Atlantic City was a pleasure palace filled with holiday makers. Ironically, given how the board game is played, the race to buy up property and develop hotels has all but ruined Atlantic City. Today in winter it feels like a gilded ghost town, dominated by bankruptcy and the threat of unemployment—a startling modern parable to the perils of greed and gambling, you can’t help but think that Elizabeth Magie would sadly nod her head and say “I tried to warn you.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook