Moses Was Tripping, And Other Scientific Explanations For Biblical Miracles

God appears to Moses as a burning bush, as depicted by Eugène Pluchart in 1848. (Image: Hazhk/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Thomas Jefferson was a great fan of Jesus. The author of the Declaration of Independence called the Son of God “the greatest of all the Reformers,” a font of “eloquence and fine imagination,” and the author of “a system of the most sublime morality which has ever fallen from the lips of man.” He wrote of him often, and tried to keep his teachings in mind.

But there was one catch—Jefferson didn’t think Jesus was the son of God. Indeed, he didn’t believe in miracles at all. So for a couple of evenings in February of 1804, after he had gone through the day’s papers and correspondence, the then-President kicked back in the White House, pulled out a razor and some glue, and did something out of a Congressional Republican’s worst nightmare: he cut the parts he didn’t like out of the New Testament, and stuck the parts he did like together again.

The cover of Jefferson’s Bible, itself now dismembered for conservation purposes. (Image: Smithsonian American Museum of Natural History/WikiCommons CC0 1.0)

The resulting Frankenbook—now known as the Jefferson Bible—”abstracts what is really [Jesus’] from the rubbish in which it is buried,” Jefferson explained 15 years later in a letter to his secretary, William Short. That rubbish included the concept of the Trinity (which he called “mere Abracadabra”) immaculate conception (which he predicted would someday be “classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the brain of Jupiter”), and nearly everything else with a hint of hocus-pocus. “If necessary to exclude the miraculous, Jefferson would cut the text even in mid-verse,” biographer Peter S. Onuf writes in Jeffersonian Legacies. His was a Bible without prophecy, resurrection, or infinite loaves and fishes; a Bible where angels feared to tread. It was only 46 pages long.

Jefferson was not the first faithful, rational person perplexed by miracles. For as long as the law of scripture has bumped up against the laws of physics, theologians, philosophers and scientists have looked for ways to reconcile the two. But in recent years, some researchers have taken things a step further. Armed with improving technology, a willingness to wade through incompatible fields, and, often, great personal conviction, they have set out to scientifically explain the definitively inexplicable.

The deepest image of the universe we have, obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2012. (Image: NASA/Public Domain)

As miracles go, the first one—the creation of everything—is a doozy. As Genesis has it, God hovered over the face of the waters for a scant six days putting everything in place. Cosmologists put the number closer to 13.8 billion years. Gerald Schroeder, a Biblical scholar and a decorated nuclear physicist, has dedicated a lot of his career to convincing people that it’s actually both. He does this, basically, by asking what a “day” is.

If you make room for relativity, Schroeder says, it’s possible that, “time is different [for humans] than it is from the perspective of the Creator.” Specifically, it’s about a trillion times slower, thanks to Schroeder’s interpretation of what he calls the “stretching factor” in Einstein’s equations. Do the rest of the math, and six of these 24-trillion-hour days come out to a little over 14 billion years. Problem solved. (In case it needs saying, experts in every possible field take issue with this interpretation, pointing out, among other things, that relativity could theoretically make “an ordinary day on Earth appear to be any length at all.”)

Moses leading the Israelites across the Red Sea, as envisioned by Nicolas Poussin in 1634. (Image: ReaverFlash/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Move along further into the Old Testament, and you find another showstopper—Moses’s parting of the Red Sea, just in time for the Israelites to cross and escape the Pharoh’s encroaching army. This event has captured the imaginations of artists for centuries, and filmmakers for decades, but it’s only in the past few years that oceanologists have started getting in on it, too.

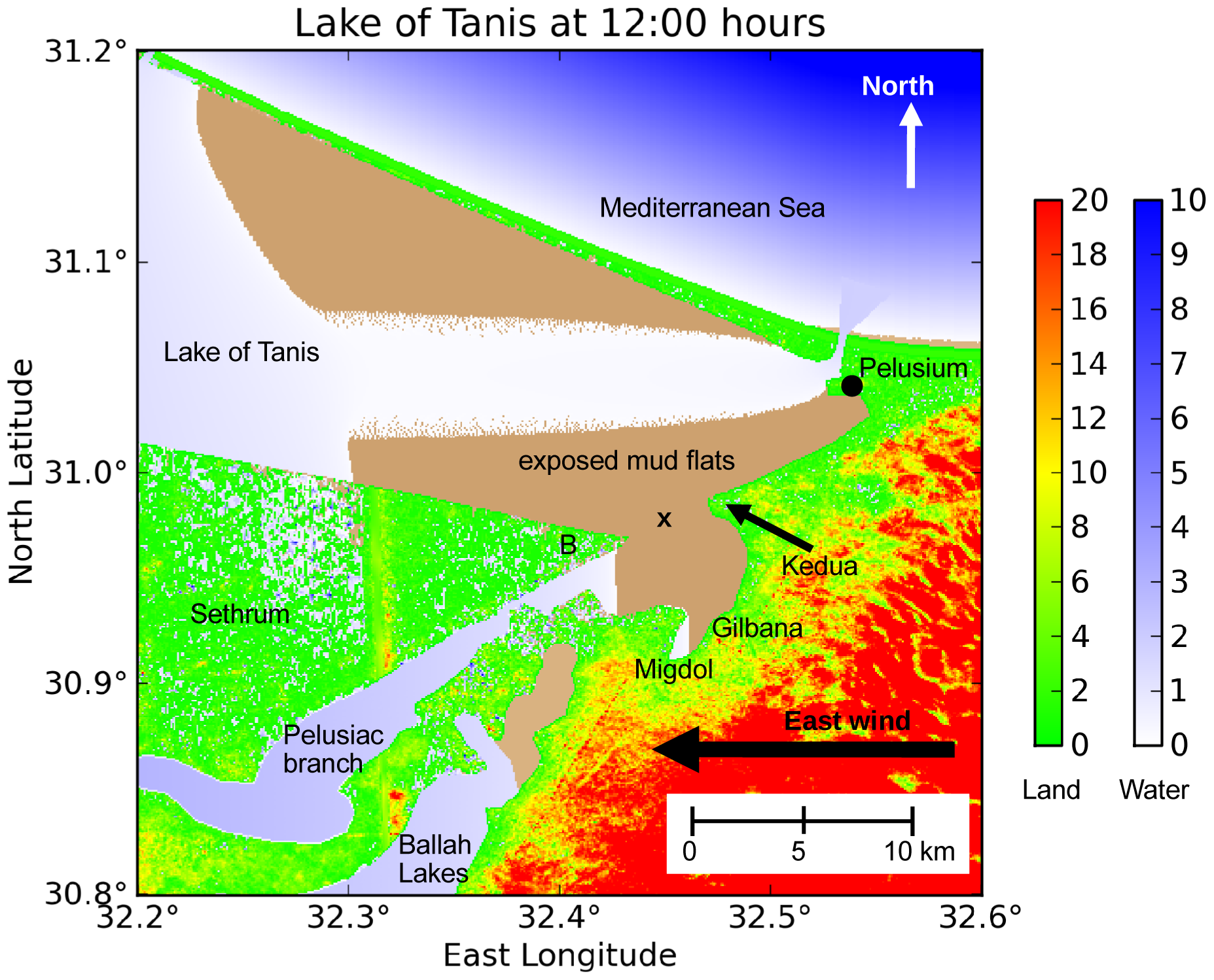

In 2010, Carl Drew, a researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), turned Exodus’s description of the Red Sea parting into a computer model. He translated the “strong east wind” into a high-but-plausible 63 miles per hour, applied it to a reconstruction of a particular spot in the Nile Delta, and concluded that this could indeed have “divided the waters.” “The wind moves the water in a way that’s in accordance with physical laws, creating a safe passage with water on two sides and then abruptly allowing the water to rush back in,” Drew explained in an NCAR press release. This would have given Moses and his followers about four hours to get across. Other researchers have proposed alternate scenarios, including hurricane-grade winds over a shallow reef, or the site of the crossing actually being a reed-clogged lake.

Another Moses classic, the burning bush, has been subject to similar treatment. Colin Humphries, a materials scientist, thinks it was an acacia bush on top of a volcanic vent, while a couple of oil researchers postulate a “volatile isoprene cloud” emitted by a particular herbaceous plant. Others think Moses may have been tripping on a common plant-derived hallucinogenic.

Moses leading the Israelites across the Red Sea, as envisioned by in Carl Drews in 2010. (Image: Drews C, Han W/PLoS ONE)

In 2011, three Boston-area psychologists decided to take a look at miracles from another perspective—perhaps they were real, but only to those performing them. Their paper, “The Role of Psychotic Disorders in Religious History Considered,” attempts to retroactively diagnoses a quartet of renowned miracle-makers. Through their lens, Abraham’s and Moses’ divine orders could have been manifestations of paranoid schizophrenia, Jesus’s crucifixion may have been “suicide-by-proxy,” and the thorn in St. Paul’s flesh was probably epilepsy.

“These findings support the possibility that persons with primary and mood disorder-associated psychotic symptoms have had a monumental influence on the shaping of Western civilization,” they write, saying that they hope their article will “translate into increased compassion and understanding for persons living with mental illness.”

Thus far, scientists have been silent on most of the New Testament feats—no nutritionists have tackled the loaves and fishes, and only vintners transform water into wine. (A notable exception is walking on water, which, according to a team of Israeli scientists, could have been accomplished with some well-placed stones.) But as technology improves, this may change—imagine what epidemiologists could do if they cracked the secret to divine healing. If this trend keeps up, anything that fell prey to Jefferson’s razor could be redeemed by Occam’s.

Update, 9/28: The original version of this article said Jefferson was the author of the Constitution, not the Declaration. Thanks to Anna Berkes for the correction, and we regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook