Would You Like Some Heroin For Your Cough?

It’s 1898. You wake up on a cold morning and the full effects of a cold hit you: coughing, sneezing, and a terrible fever. Like any self-respecting American in the latter half of the 19th century, you pop on over to your local post office or hairdresser in search of a remedy. There, you buy a small vial of liquid with some fantastic name like “Dr. Seth Arnold’s Balsam” or “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup”. The packaging claims that it cures anything from a toothache to a full-blown cold just five minutes flat. What the packaging doesn’t say, of course, is that the ‘medicine,’ which is applied topically to the skin, contains opium, morphine, and alcohol.

Welcome to the world of patent medicine.

Patent medicines reached peak popularity at the turn of the 20th century. While the name implies some sort of regulation behind the creation of these compounds, nothing could be further from the truth. Patent medicines were anything that people trademarked and sold as medicine–whether or not they actually worked was beside the point. Manufacturers intentionally suppressed the true ingredients of their remedies in order to woo new customers. If it doesn’t actually cure your cold, the high dose of cocaine might trick you into thinking otherwise.

With mounting concern from doctors and government officials, the use of patent medicines was slowly phased out with the creation of the Food and Drug Administration in 1906, and the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act that regulated the distribution of opiates and cocoa products in 1914. However, the use of patent medicines persisted until the passing of the Controlled Substances Act by the Nixon Administration in 1970-finally disallowing the use of narcotics in medicine.

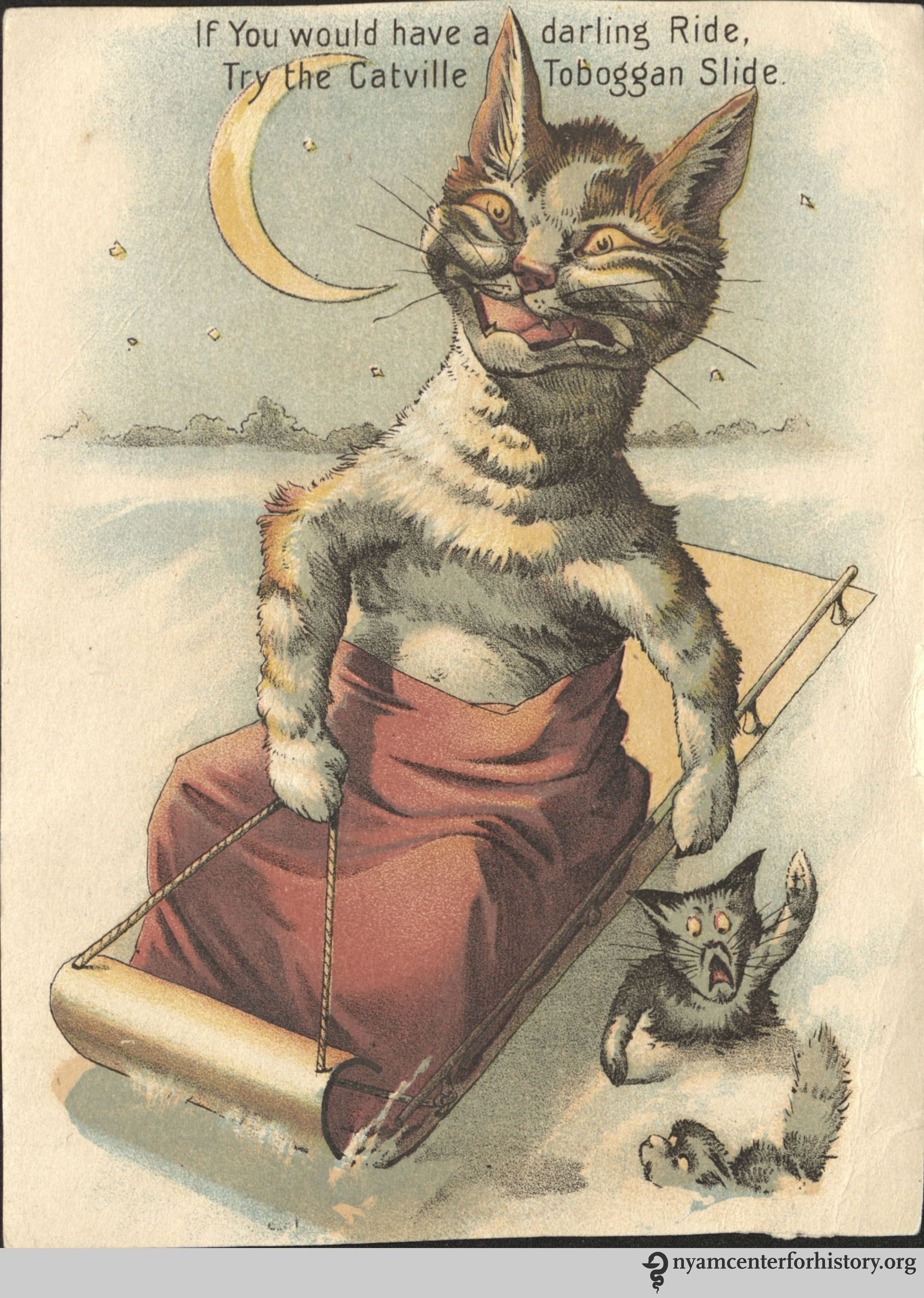

Much to our delight, the good folks at the Library of the New York Academy of Medicine immortalized this sordid chapter in medical history with a digitized collection of trade cards and medical advertisements. Trade cards served as promotions for a particular product, and were distributed to directly to pharmacies and other local outlets. By the late 19th century, the trade cards for the more popular medicines became collector’s items in the same vein as baseball or Pokemon cards today. The following is a list of the most outrageous trade cards and medical advertisements from the heyday of the snake oil salesman, all from prior to 1923.

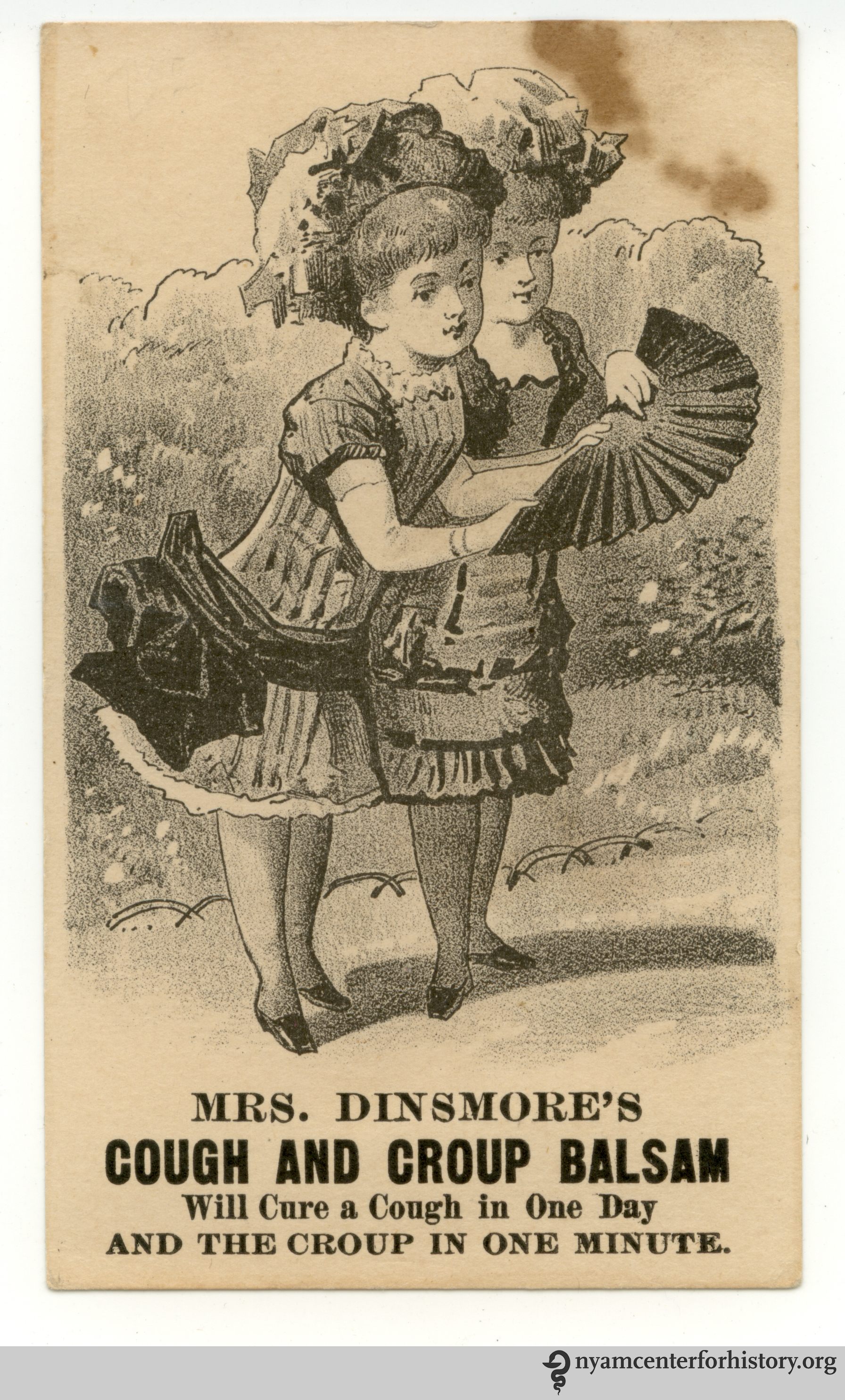

Mrs. Dinsmore’s Cough and Croup Balsam

Ever wanted to cure the croup in one minute or less? Well, here’s the perfect remedy! Created in 1870, Mrs. Dinsmore’s Cough and Croup Balsam contained nothing more than a hearty dose of alcohol with a few chemicals mixed in for flavor. Here’s where it gets strange–Mrs. Dinsmore was actually the chemist Mr. Alfred Dinsmore, who thought he could sell more medicine with a woman’s face on the bottle rather than his own.

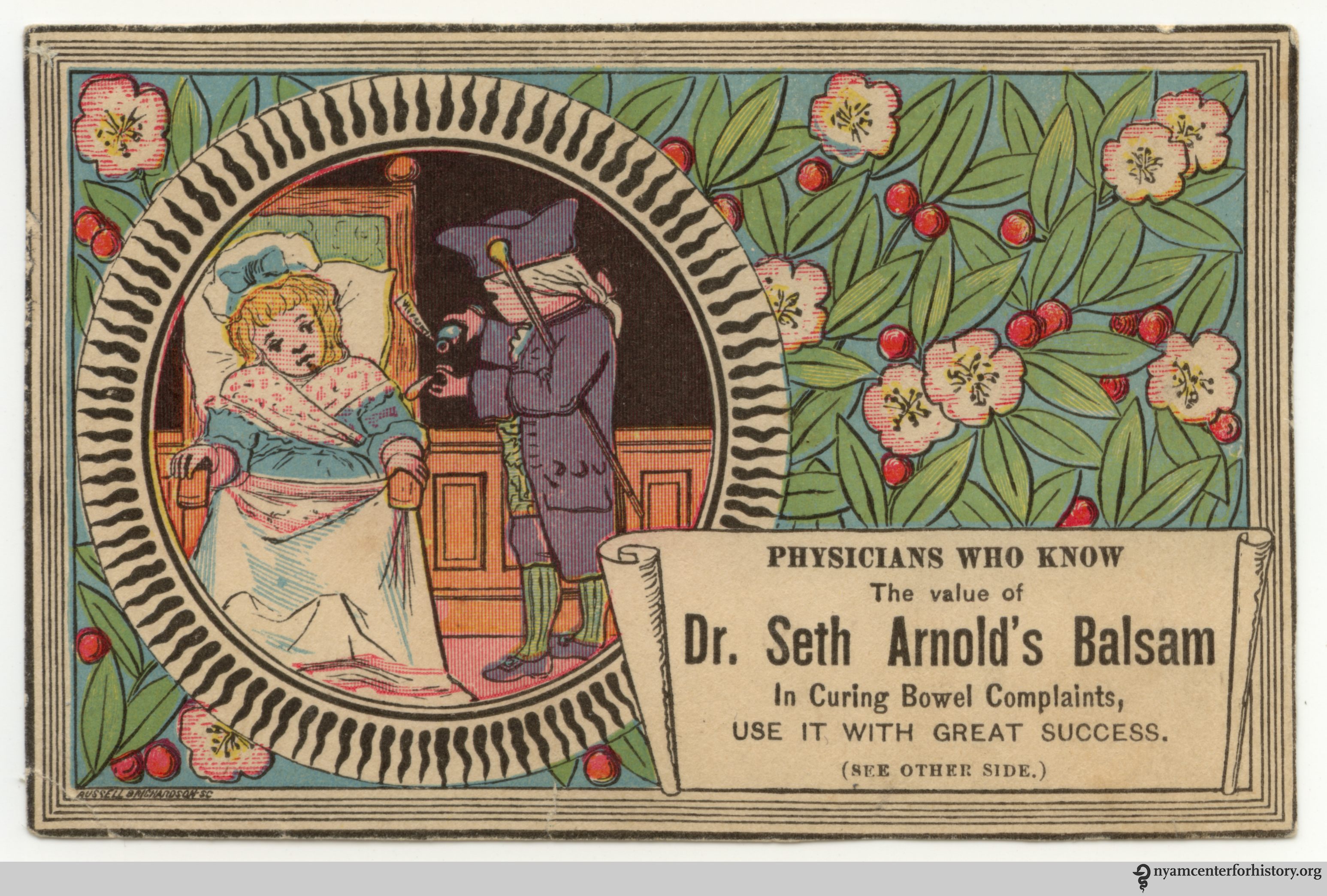

Dr. Seth Arnold’s Balsam

One of the weirdest ads in the collection depicts a colonial-era man giving a woman clearly suffering from bowel ailments a nice cup of Dr. Seth Arnold’s Balsam against a backdrop of flowers. Unlike some of his other competitors, Dr. Arnold appears to be a licensed medical practitioner, on record as running a namesake laboratory in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Dr. Arnold peddled his balsam as a quick cure for any bowel discomfort caused by cholera, dysentery, or diarrhea - the regular litany of ailments for any 19th century urban dweller.

Dr. Ingham’s Nervine Pain Extractor

With a name that is sure to make any child cower in fear, Dr. Ingham’s Nervine Pain Extractor is a curiously titled remedy for assorted stomach ailments including dysentery, worms, cramping, croup, and cholera. While Dr. Ingham went to great lengths to suppress the true ingredients of his remedy –as it was intentionally marketed to children – a 1915 lawsuit revealed that it actually contained 86% alcohol, opium alkaloids (morphine), camphor, and capsicum. The lawsuit found that Dr. Ingham’s Nervine Pain Extractor did not actually contain any effective medicinal ingredients.

Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup

It gets tiring when your baby is crying all night. For quick relief, try Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup. First formulated by a Mrs. Charlotte N. Winslow in Bangor, Maine in 1849, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup was created to subdue restless infants (and baby animals) during painful teething episodes. With 65 milligrams of morphine per fluid ounce, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup was likely pretty effective for adults as well.

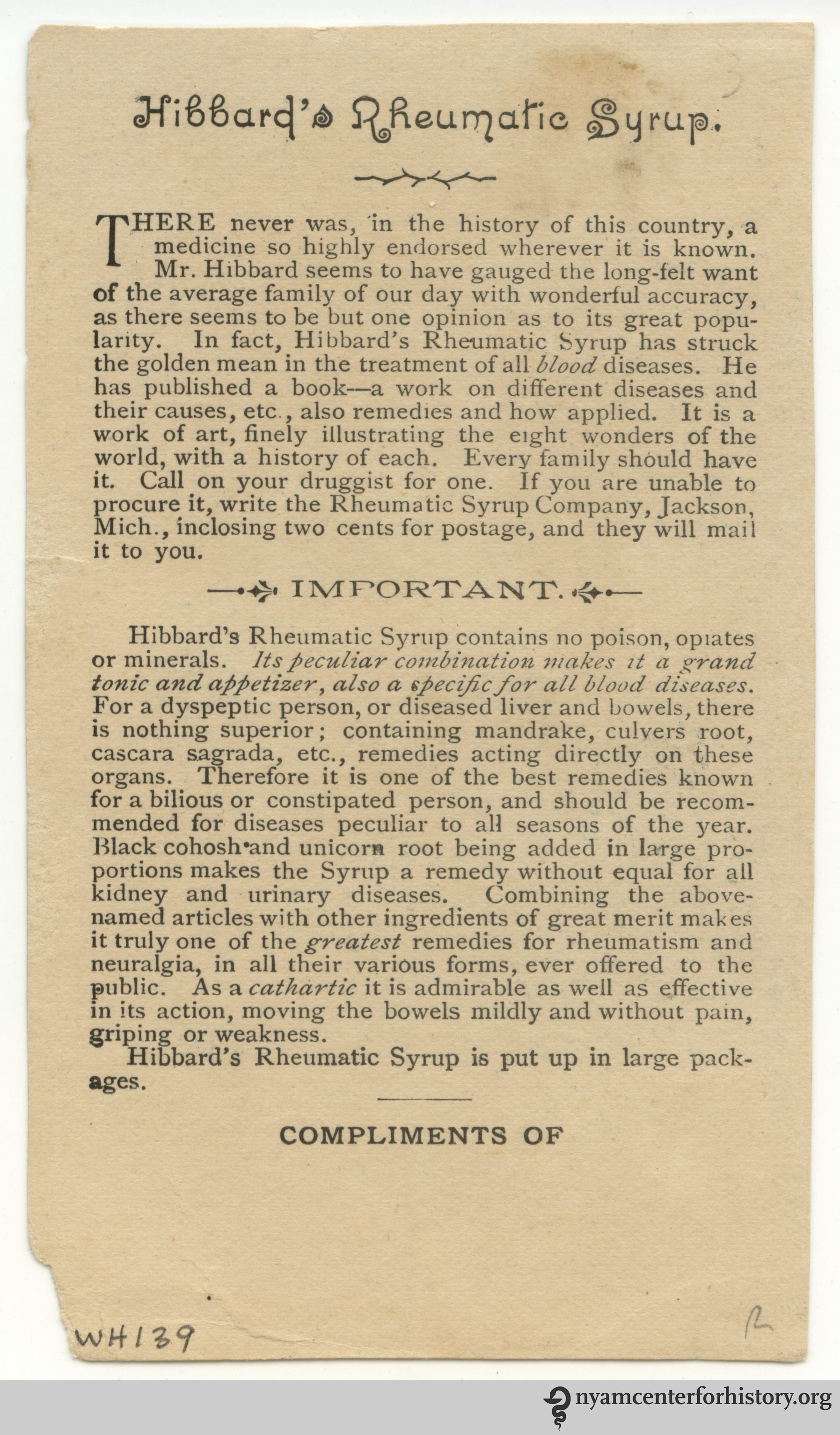

Hubbard’s Rheumatic Syrup and Plasters

Hibbard’s Rheumatic Syrup is an anomaly for this list: the manufacturers claim that it contains no known opiates. That notwithstanding, Hibbard’s Rheumatic Syrup is an alcohol-based remedy for all blood, liver, urinary, and kidney diseases, as well as constipation. While the real ingredients for Hibbard’s Rheumatic Syrup are hard to pin down, the trade card states that “black cohosh and unicorn root” are added to the syrup in large proportions during the manufacturing process.

Hibbard’s Rheumatic Syrup Trade Card (Back)

Dr. Radcliffe’s Great Remedy

Dr. Radcliffe’s Great Remedy or Seven Seals or Golden Wonder or The Great Vegetable Pain Destroyer (all names refer to one product) was first created by R. Monroe Kennedy in Pittsburgh, in 1872. Reportedly containing chloroform, red pepper, camphor, and peppermint oil, the remedy was used as a painkiller. This trade card dates to the early 1880s, and offers a “no cure, no pay” guarantee.

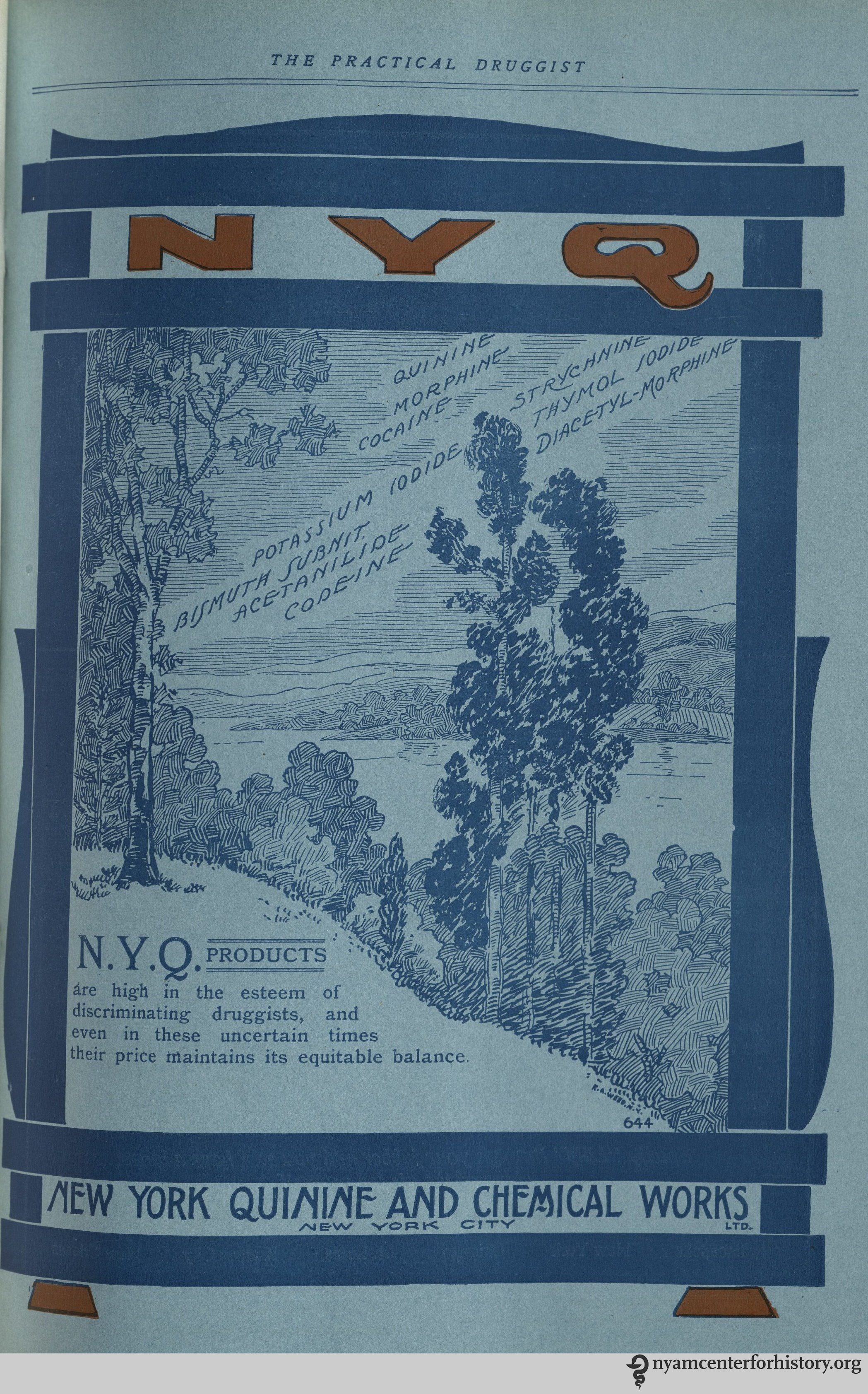

New York Quinine

Pictured above is a 1917 Practical Druggist ad for New York Quinine and Chemical Works (N.Y.Q.). On offer are the classic staples of the early 20th century pharmacy–morphine, strychnine, heroin, and quinine.

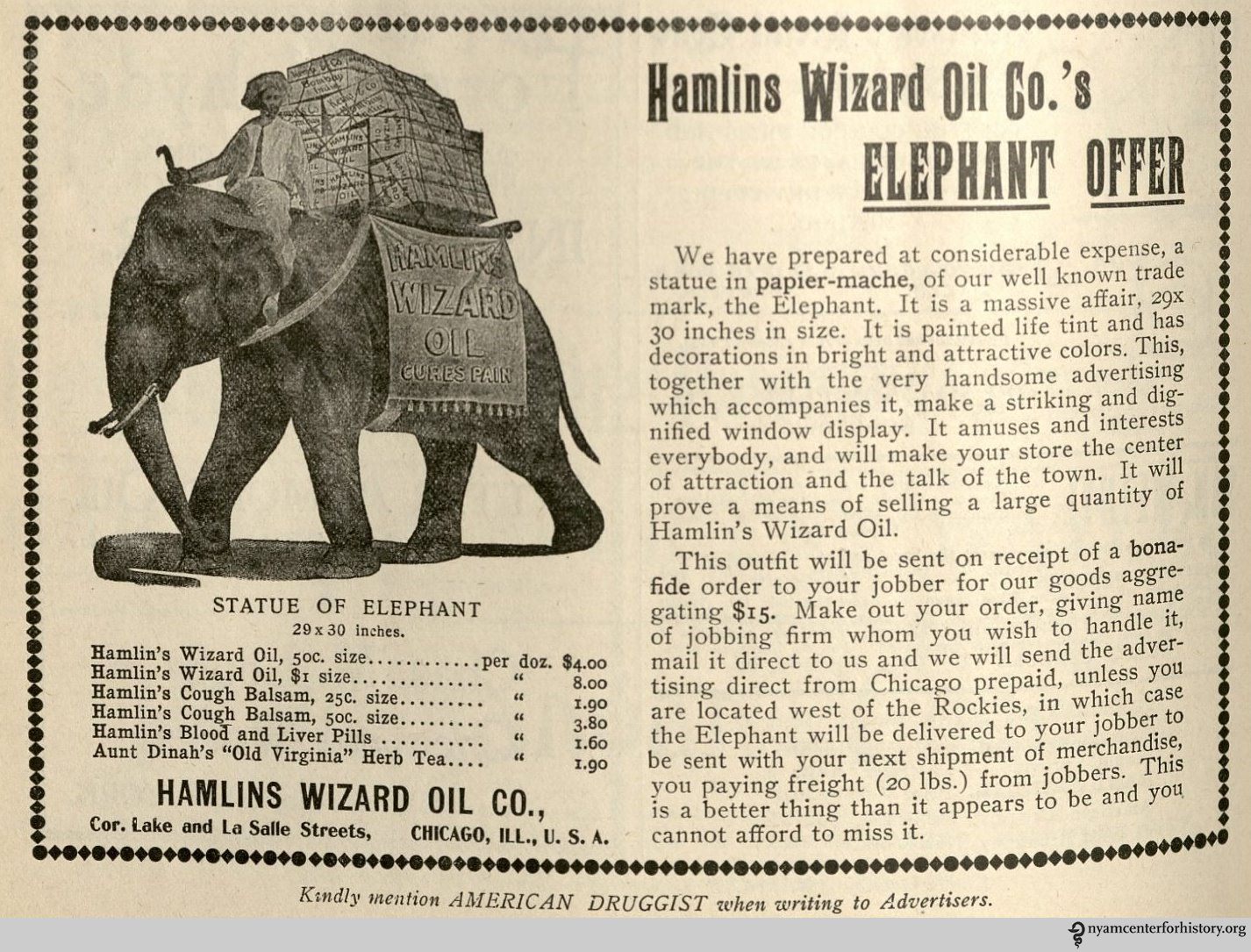

Hamlin’s Wizard Oil Co.

American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record,v.36, no. 9 April 23, 1900

Hamlin’s Wizard Oil Co was founded in 1861 by the brothers John and Lysander Hamlin–magicians by trade. Containing 50-70% alcohol, depending on the batch, along with a host of other fun compounds such as turpentine, ammonia, and chloroform, the magicians marketed their Wizard Oil as a cure-all for anything from cancer to toothaches. The efficacy of Hamlin’s Wizard Oil as a cure for cancer must have been called into question by 1900, as they saw it fit to give vendors a papier-mâché elephant in order to boost sales of their miracle medicine.

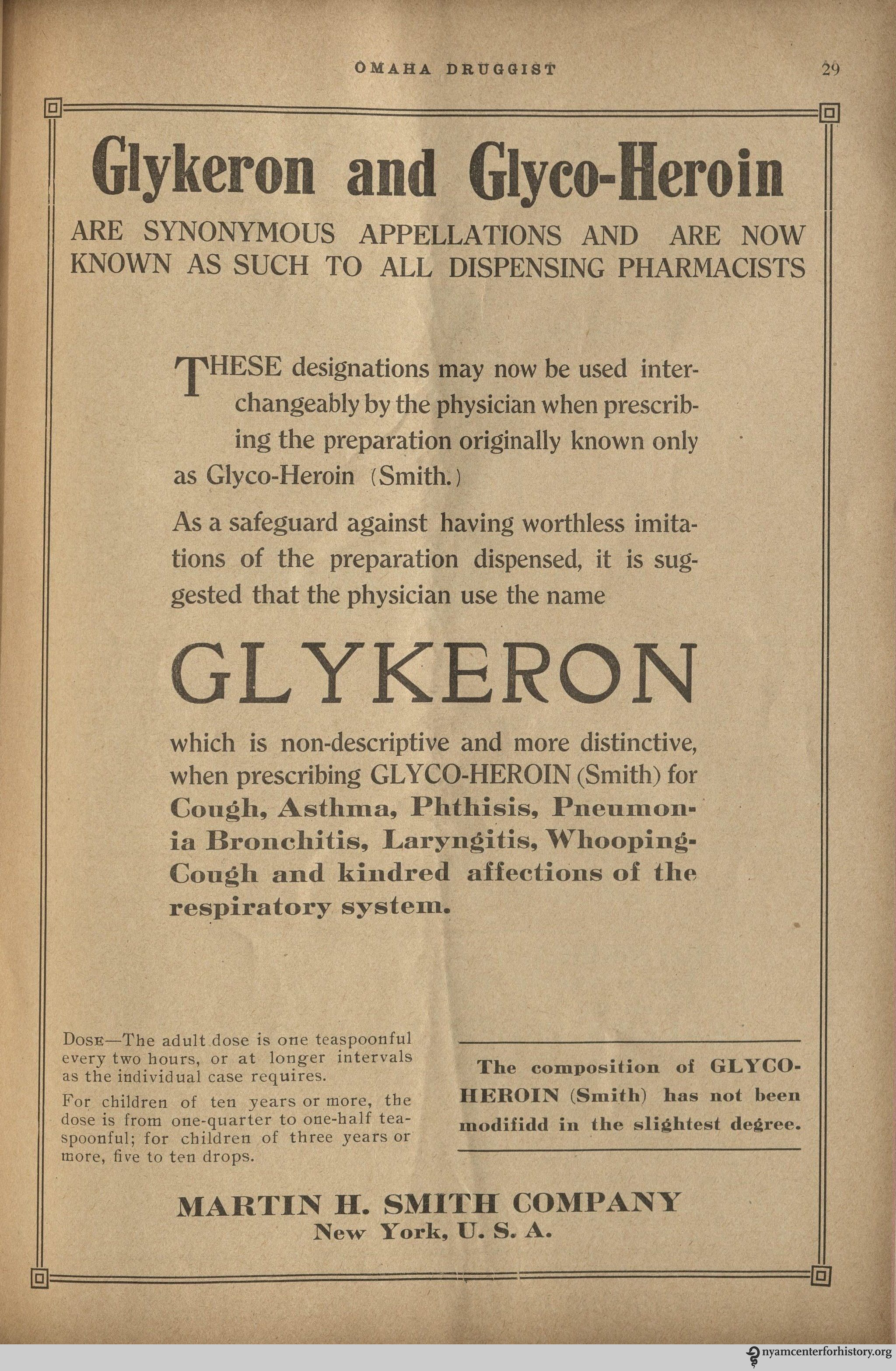

Glykeron

Seen here in an 1899 Practical Druggist ad, Glykeron was the Martin H. Smith Company’s trademarked glyco-heroin. First synthesized from poppy plants in 1874, heroin was hailed as a non-addictive substitute for morphine. Smith’s Glykeron, according to the ad, was especially effective for a range of respiratory illnesses. In an uncharacteristic nod towards safety, the Smith company recommended giving children a smaller dose than adults.

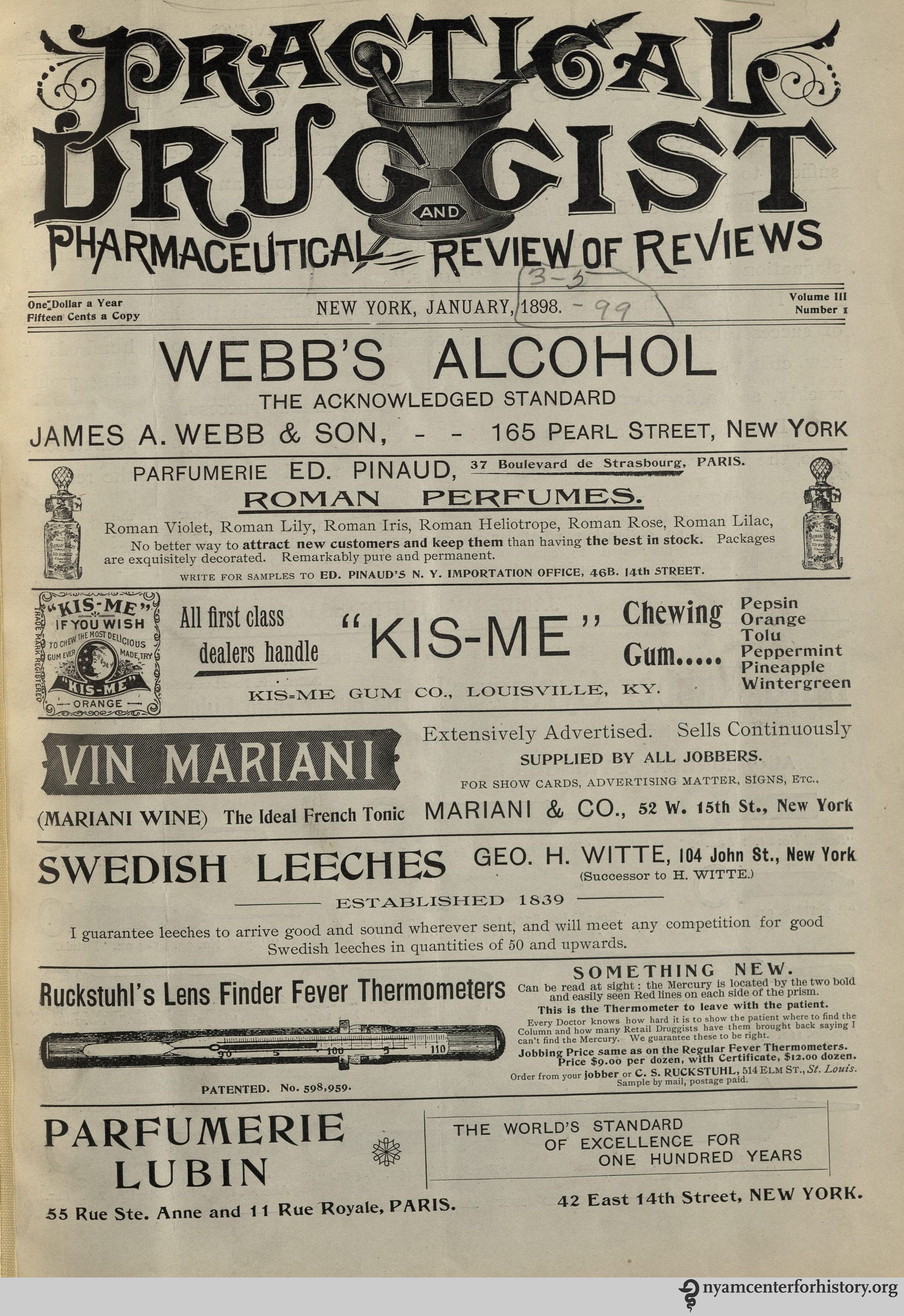

Vin Mariani

The Practical Druggist and Review of Reviews, v.3, no. 1 January 1898.

The Practical Druggist and Review of Reviews, v.3, no. 1 January 1898.

This 1898 issue of Practical Druggist depicts Vin Mariani, a wine-based tonic created by the French chemist Angelo Mariani in 1863. After his curiosity was piqued about the commercial and medical applications of cocaine, Mariani decided to mix coca leaves into vats of Bordeaux and market his elixir as Vin Mariani. The end result was a wine with 7.2 milligrams of cocaine per ounce. Winning over notable people such as Pope Leo, who bestowed a Vatican gold medal to the wine, and Thomas Edison, who claimed that the wine helped him stay awake and work longer hours.

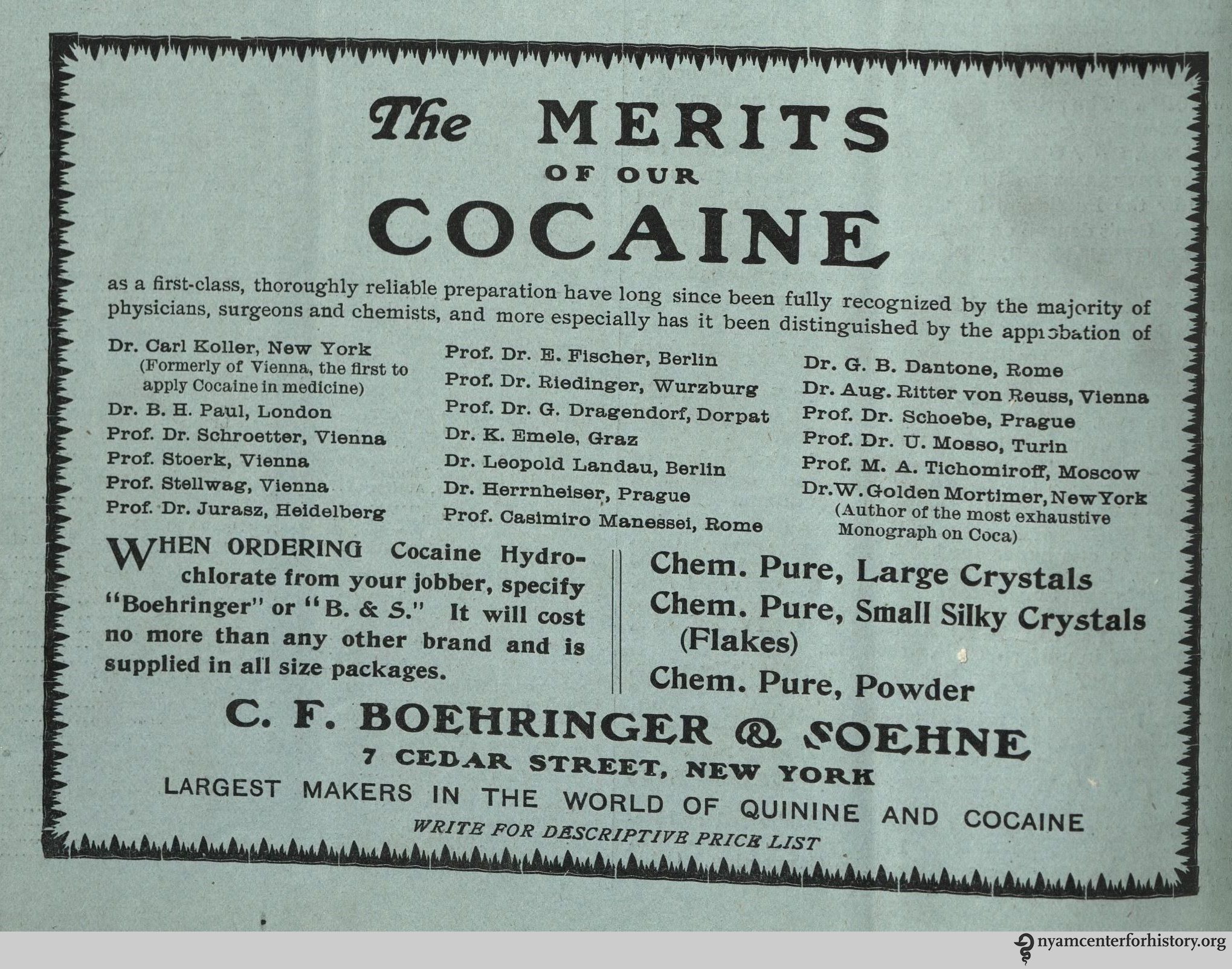

Boehringer & Soehne Cocaine

The Practical Druggist and Review of Reviews,gist v. 22, no.2 August 1907

Founded in 1885 in Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany, by Albert Boehringer, Boehringer & Soehne (B & S) was one of the leading pharmaceutical companies of its era, mostly selling quinine and cocaine. Still in operation today (as Boehringer Ingelheim), the company prided itself on distributing the most beautiful, well defined cocaine crystals. This 1907 Practical Druggist ad discusses the ‘merits’ of B & S cocaine, as well as all of the doctors who espouse the use of cocaine as medicine.

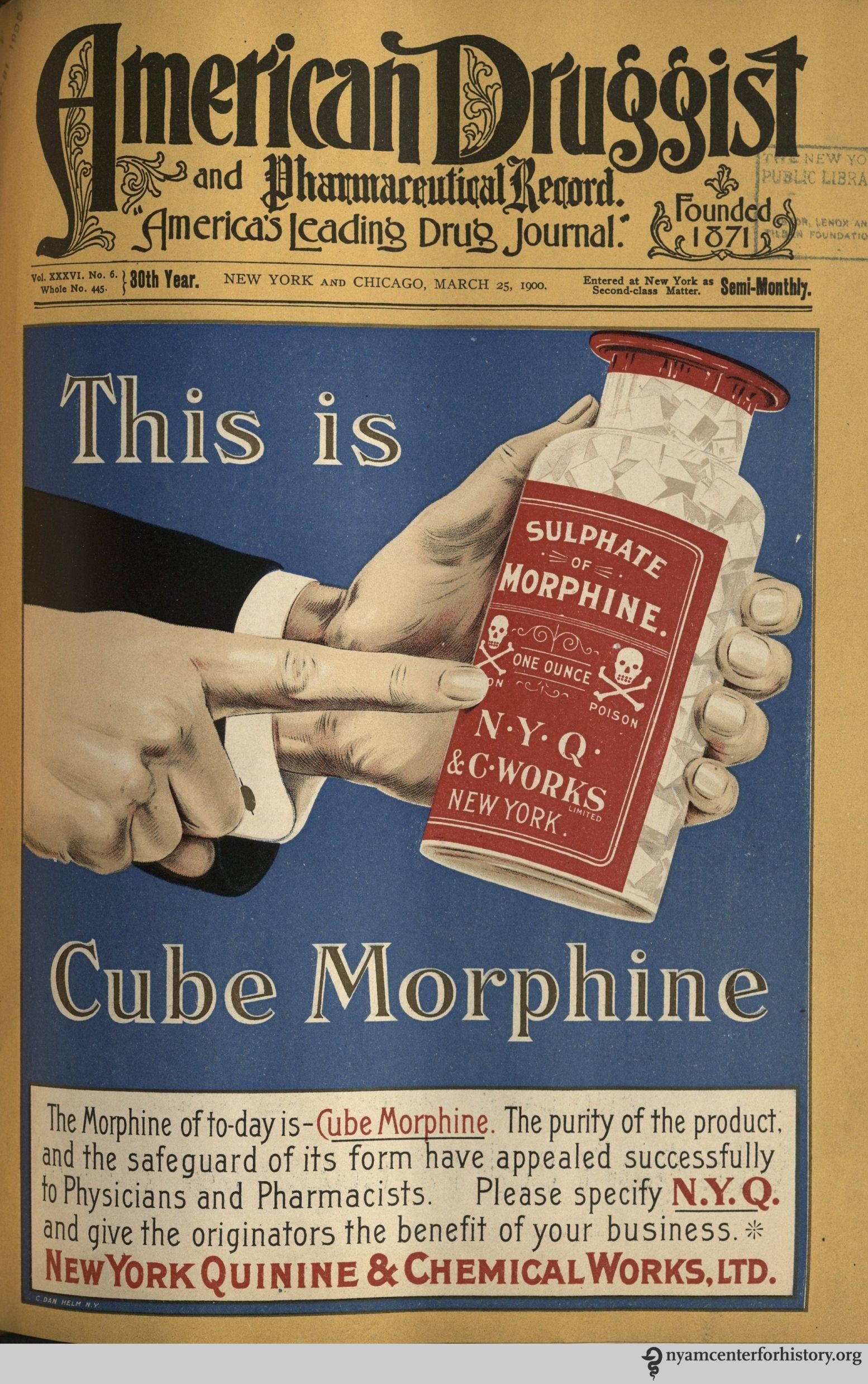

Cube Morphine

American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record, v.36, no. 6 March 25, 1900

Cube Morphine, seen in this 1900 American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record ad, was the cure-du-jour for all things painful. First synthesized in the opening days of the 19th century by Friedrich Wilhelm Serturner as a more effective pain reliever than regular opium, cube morphine became wildly popular among injured Civil War veterans. Morphine’s popularity led to its downfall in medicine as its addictive properties became clear - giving morphine addiction the moniker “Soldier’s Disease” after the soldiers who became widely addicted.

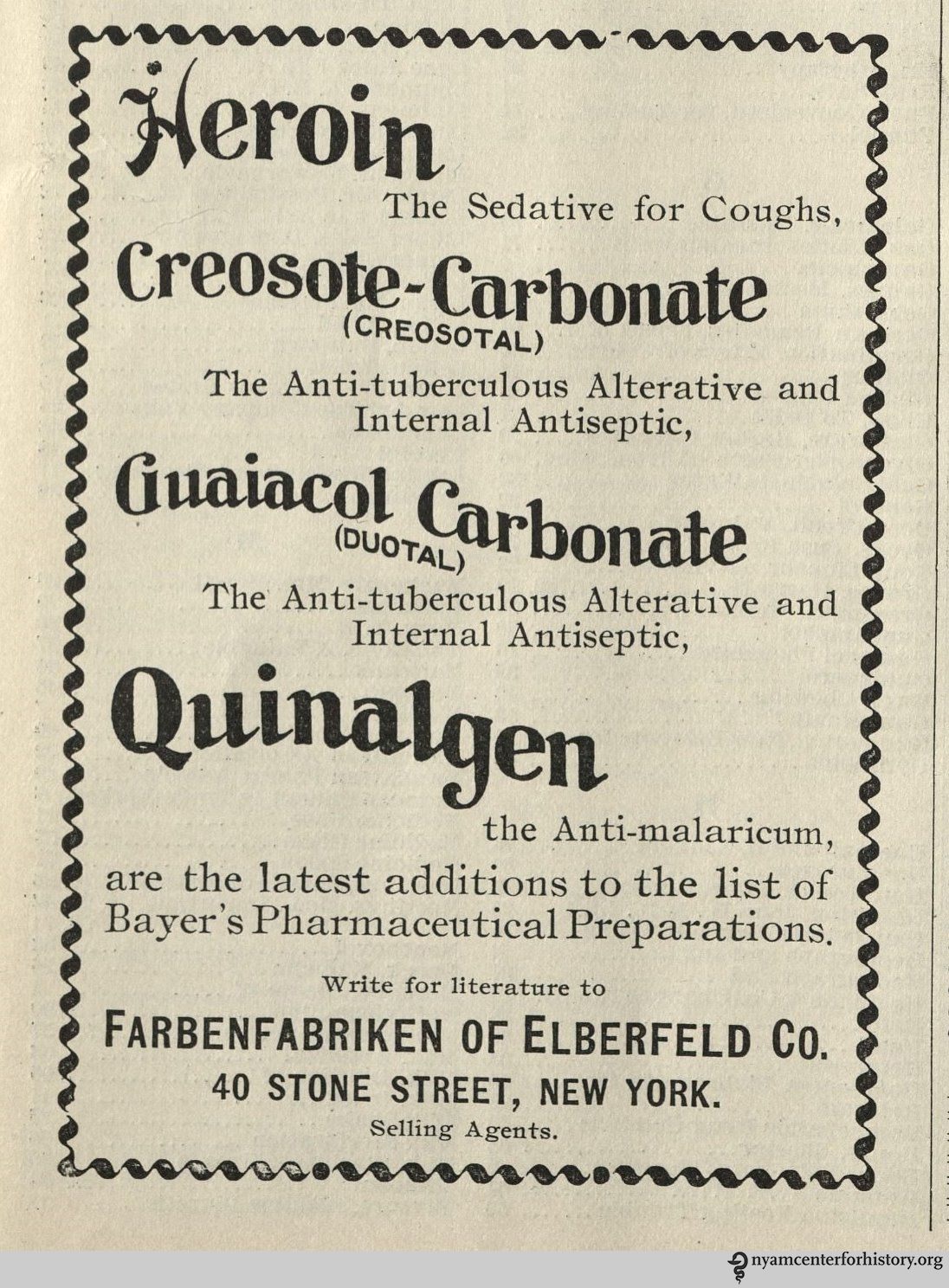

Bayer’s Heroin

The Practical Druggist and Review of Reviews,v.5, no. 5 May 1899

Bayer is a company you probably know. In the 1890s, Bayer did brisk business for two main reasons: aspirin and heroin. Bayer’s Aspirin has been curing headaches for well over a hundred years and has remained remarkably unchanged since it was first synthesized in Bayer’s labs. Heroin, however, took on a much more nefarious role. Seen here in a 1899 Practical Druggist ad, heroin was first marketed by Bayer in 1898 as a cough and cold medicine. Allegedly, the name “heroin” comes from the German “heroisch” which means heroic and strong–probably the way the researchers felt after dosing themselves for the first time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook