How Newport, Kentucky, Lost the Title of ‘Sin City’

Before there was Vegas, there was another American hot spot for bad behavior.

Long before Las Vegas wore the crown of America’s “Sin City,” there was Newport, Kentucky.

Today Newport is a small, upstanding U.S. city near Cincinnati, yet during Prohibition, and for decades after, Newport was a hotbed of gambling, prostitution, organized crime, and widespread corruption.

If you had no idea that Newport once had this reputation, don’t feel too bad. In large part, that’s likely because its age of corruption just didn’t last. By the 1960s, the city was ready for a change. And the unlikely event that kicked off the city’s transition? A pulpy scandal involving, of all things, the frame-up of a former football star. So buckle-up, dear readers, for the story of Newport, George Ratterman, and the Night That Never Was.

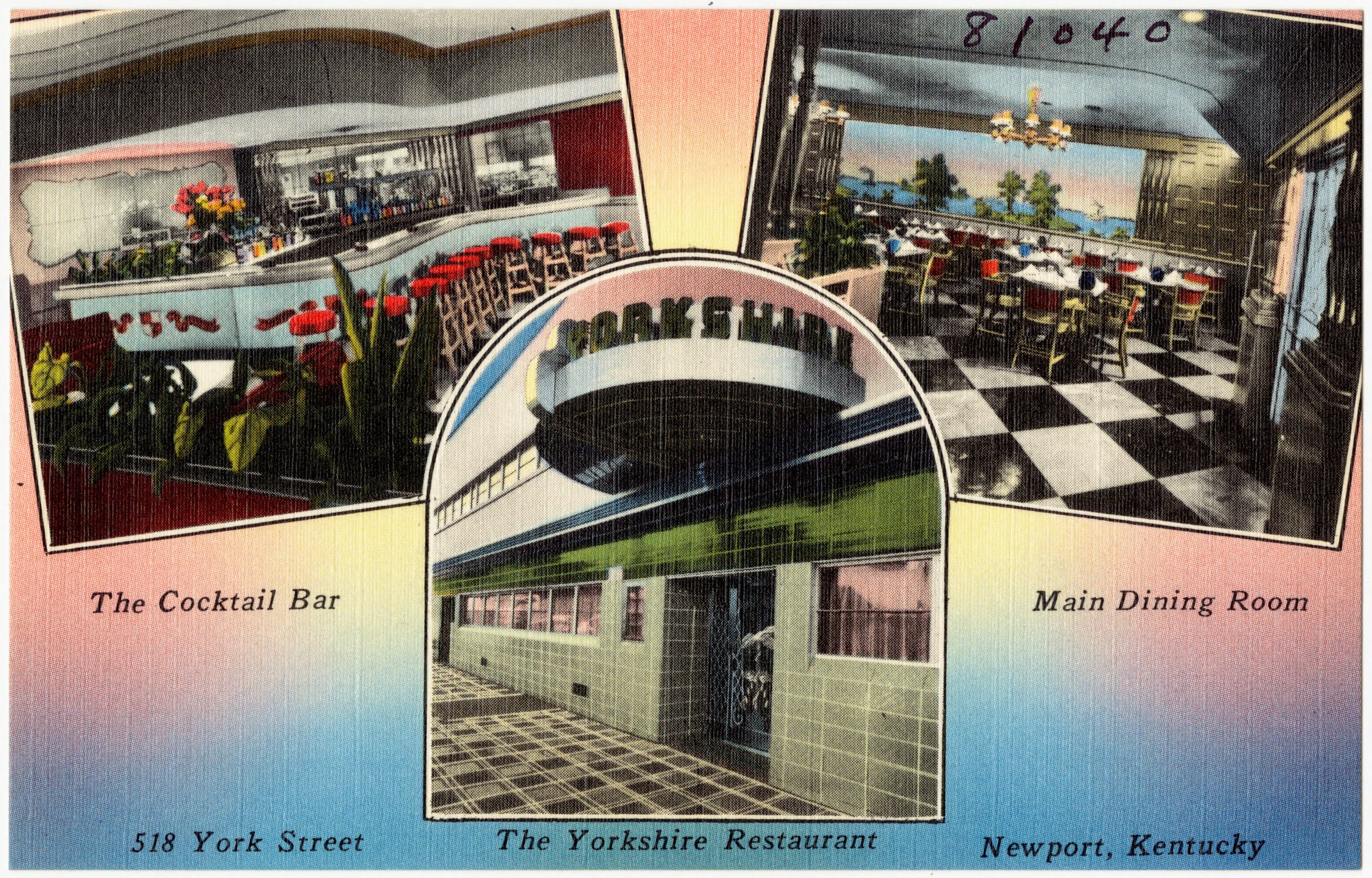

First established in 1795, the city of Newport grew steadily on its waterfront spot at a convergence of the Ohio and Licking Rivers. The first signs of trouble began during the Civil War, when a prostitution industry sprung up to serve Union soldiers stationed on the Ohio side of the river. By the 1920s, Prohibition brought a widespread criminal element to the city, as speakeasies (or “tiger blinds” as they were known in local slang) began appearing. Just across the Ohio River, Cincinnati would come to be known as one of the hearts of bootlegging in the day, but much of what was sold and moved through that city came from Newport.

When Prohibition ended in 1933, the entrenched criminal underworld in Newport had to find other sources of revenue, and a number of casinos and brothels moved in to fill the void, bringing with them widespread institutional corruption among the police and local government. During this time, the city was under the constant sway of gangland mob bosses, and violence wasn’t uncommon as various factions competed with one another.

Over the next couple of decades, the city of Newport enjoyed a solid reputation as a sin city, but by the late 1950s, things began to change. The growing desert city of Las Vegas had begun to lure the attention of serious criminal enterprises, and Newport’s star as a mecca of gambling and prostitution had begun to fade. By the early 1960s, locals were ready for a change as well.

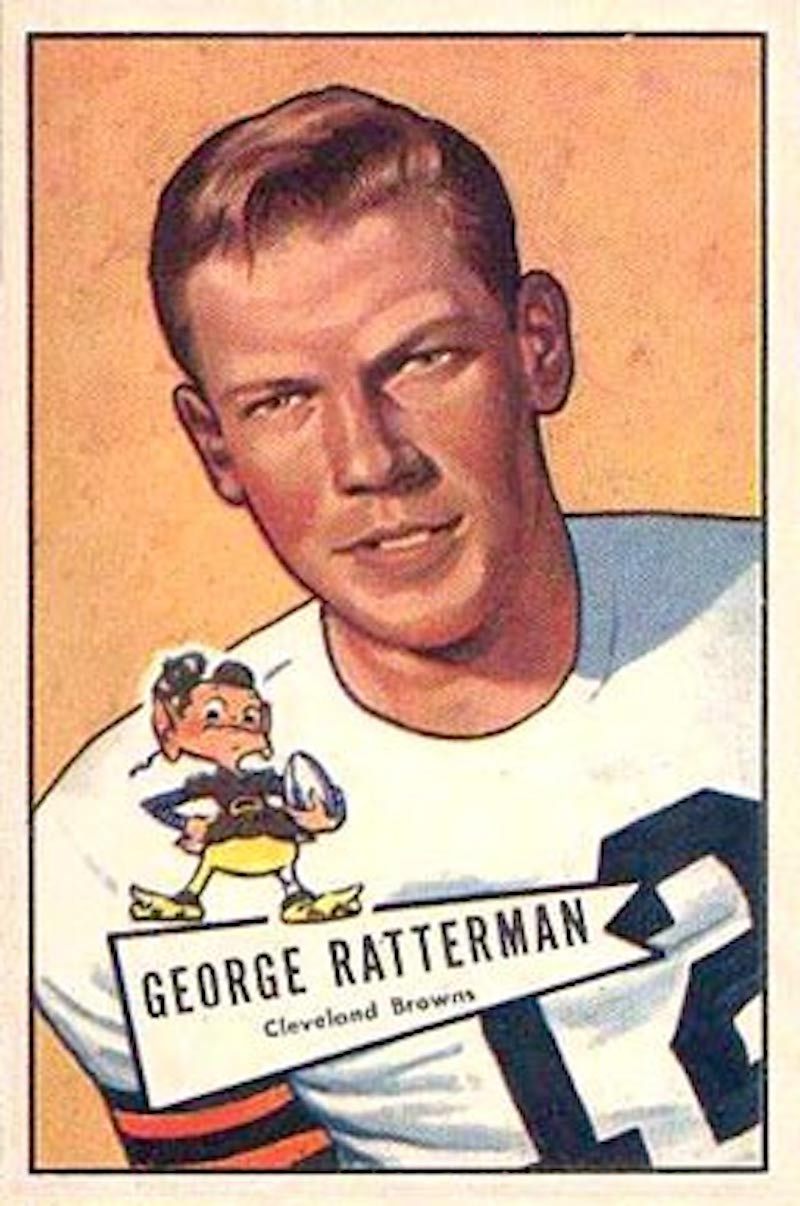

A civic organization known as the Committee of 500 rose to prominence around this time, made up of Newport residents who wanted to take the city back after decades of corruption. The group was growing quickly, but they needed a face to put to the cause, and they found the perfect mug in the All-American square jaw of a former football star, George Ratterman.

Ratterman, a native of Cincinnati, had made a name for himself in the mid-1940s playing college sports at Notre Dame, including tennis, baseball, basketball, and most notably, football. He went on to a career in the fledgling NFL, playing for teams including the Buffalo Bills, the New York Yanks, and finally the Cleveland Browns. Ratterman gained a headstrong reputation that led The New York Times to refer to him as a “cocky little blond.” Two weeks after appearing on the cover of Sports Illustrated, he blew out his knee, and officially ended his professional sports career in 1957.

As a footballer, Ratterman cut an almost cartoonish figure of the handsome, corn-fed American hero, so he made a perfect law-and-order candidate for Newport sheriff. According to a 1999 article in the now defunct Cincinnati Post, by 1961, Ratterman was the married father of eight children, working both as a part-time sports commentator and in financial planning. He announced his campaign for sheriff of Newport in April of 1961, saying, “I am told that if I run for sheriff, I will be the victim of all sorts of personal slanderous attacks. But I say to our opponents, let the attacks start now, if they must. Let the battle be joined now.”

Just over a month later, he woke up in bed next to a stripper.

Shortly before 3 a.m. on May 9, 1961, Ratterman was arrested at the Glenn Hotel in Newport on charges related to prostitution, based on an anonymous tip. When detectives burst into the room they found Ratterman half-naked and in bed with a 26-year-old exotic dancer called April Flowers (real name, Juanita Hodges). Ratterman had no idea where he was and said he couldn’t remember how he had gotten there. Nonetheless, the police brought him in, and he was promptly bailed out by his lawyer.

The night before, Ratterman had met with a former football associate, Tito Carinci, who just so happened to be president of the Glenn Hotel and its nightclub, the Tropicana. Not wanting to be seen in Carinci’s joint, they met for a drink in Cincinnati. But after just one drink, Ratterman claimed he’d lost track of the night, remembering only being in a strange apartment and at one point having people pull at his clothes. With no memory of his previous night to use as a defense, it would prove hard for him to shake the story of his arrest. Or it would have, if his obvious frame-up hadn’t been such a botch job.

His sensational arrest quickly hit the national papers, but the whole affair fell apart nearly instantly during Ratterman’s trial, a week later.

Still foggy, Ratterman had been taken to his physician just hours after his arrest. At the hospital, doctors took blood and urine samples which, after testing, showed large amounts of chloral hydrate, an early date-rape drug sometimes called “knockout drops.” Clearly he had been set up. One doctor estimated that Ratterman had been given a triple dose.

Ratterman and his lawyer had one other ace up their sleeve in the form of a freelance photographer named Thomas Withrow. According to The New York Times, the photographer testified that he’d been approached by Carcini three weeks prior to Ratterman’s arrest and told to be ready to snap pictures of a man and a woman in a hotel. Carcini told him that someone would open the door and Withrow would have to run in, quickly take photos, and run out. Withrow never went through with the deal, but with his testimony, the blackmailers’ plot was sunk.

The plan to discredit and intimidate Ratterman backfired in just about every possible way. All charges against Ratterman were dropped, and he easily won the sheriff’s seat later that year on a wave of sympathy. Carcini, Hodges, the arresting officers, and others eventually became the target of investigations and prosecution.

Maybe the most influential fallout from Ratterman’s arrest came straight from the top. U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, already on a crusade against organized crime, took a special interest in Newport after hearing about the case, sending dozens of FBI agents to the town to help with the investigation. Once the Feds, angry locals, and righteous heroes such as Ratterman combined forces in Newport, the days of Sin City were over.

Ratterman served as sheriff for just four years, but by the end of his tenure it seems the criminals that had held sway in the city for so long were pretty much leaving on their own. In his New York Times obituary, Ratterman, who passed away in 2007 at the age of 80, is quoted as saying that while his officers had to kick in a few doors, “the other side knew what was coming, and they left quietly, on their own. We knew who was in charge of the corruption, and they knew we knew.”

Whether it was Ratterman’s direct influence, or simply the changing habits of the underworld, Newport shook its criminal image by the end of the 1980s. Today, the title of Sin City is so firmly associated with Las Vegas that it’s hard to remember that there was once another city that more than earned the name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook